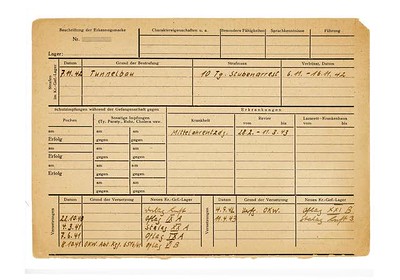

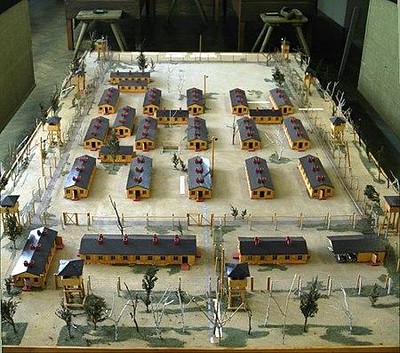

This three part post has been researched and compiled by Mitch Peeke. It is a fascinating story of Sqn. Ldr. Anthony Bridgman DFC who, if fate had dealt a different hand, may well have been in Guy Gibson’s seat when 617 Sqn. attacked the ‘Great Dams’ of the Ruhr. Anthony Bridgman was also in Stalag Luft III at the time of the ‘Wooden Horse’ breakout. His story is incredible, and appears in whole, under Heroic Tales.

My thanks go to Mitch for his remarkable research of Anthony, and to the many people who have contributed to Anthony’s story.

The Hand of Fate and Squadron Leader Anthony O. Bridgman DFC. (Part One).

By Mitch Peeke.

Squadron Leader Anthony Bridgman DFC, is a name that could have been; and perhaps should have become; a household name from the dark days of World War 2. If you know where to look, you will find him frequently mentioned in the books that were written by his RAF contemporaries. You will find that he is mentioned with affection and with very high regard too, for to them; Bridgman was practically a legend. But on the night of 23/24th September 1940, whilst returning from a raid on Berlin, the fickle hand of fate intervened and decreed that Anthony Bridgman would not fulfil what was perhaps his destiny: Another man would. That other man was somebody Bridgman knew well, a friend of his in fact; who would ultimately, daringly and famously, make Anthony Bridgman’s destiny his own. He would do it flying a Lancaster bomber over the Ruhr one moonlit night in May 1943; whilst Anthony Bridgman was a POW, “helping out” as he once succinctly put it, with the preparations for what would soon become known as The Wooden Horse Escape.

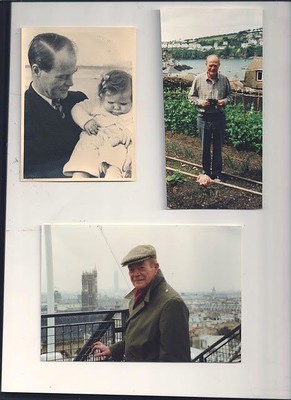

Anthony O. Bridgman was born on 4th June 1915 in North Stoke, in the parish of Keynsham, Somerset; which in turn lies on the River Avon, about four and a half miles North-west of Bath. The only reason he was born there was that he, perhaps inconsiderately, decided to enter the world whilst his parents were paying a rare visit to England. Anthony was born into a family where he would have five siblings and rather distant parents. His Father managed a Tea plantation in Munar, Southern India and as soon as it was possible, baby Anthony was taken there, where he would spend the first five years of his life. As soon as he was able to go, his parents packed him and his brother, Kit; off to Boarding School; Magdalen (pronounced “Maudlin”) College School, Oxford to be exact. Even during the school holidays, he was often “farmed out” to the locals on behalf of his parents. He was destined never to return to India, even after he finished Magdalen, at the age of eighteen.

By the time he was in the Lower 4th year, he would have been encouraged to take part in the activities of school’s Officer Cadet Unit, (OCU) before joining it became compulsory in the Lower 5th. The school’s cadet unit was at that time divided into Army, Navy and Signals, and Air Force sections. (Today, it is known as the Combined Cadet Force, or CCF. The Navy and Signals section closed comparatively recently, leaving today’s student with just the Army or Air Force sections to choose from). Tony, as he preferred to be called, had become attracted to the idea of flying and it was a dream he would pursue with vigour as an officer cadet right through to his Upper 6th.

Magdalen College School was established in 1480 as part of Oxford University’s Magdalen College. This meant that Tony, as one of the school’s Air Force Officer Cadets, had full access to the Oxford University Air Squadron. In 1933, now aged eighteen, he was to be found actively undergoing flying training, at nearby RAF Abingdon, where Oxford UAS was based.

Learning to fly 1933 (Photo courtesy of Frances Leach).

The following year, he moved on from Oxford UAS, to N0. 3 Flying Training School at RAF Grantham, for advanced flying training. If there was one thing that the now nineteen year old Tony Bridgman knew for certain, it was that Tea-growing was most definitely not in his blood! He was joining the exclusive ranks of “The Best Flying Club in the World”, as the inter-war RAF was known, and if the truth be known, he was rather enjoying it! In the photo of him taken at RAF Thornaby, he is standing beside a Hawker Hart T, having completed a cross-country exercise as part of his advanced training.

RAF Thornaby in 1934. (Photo courtesy of Frances Leach).

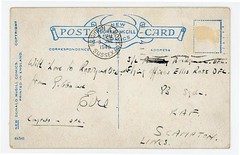

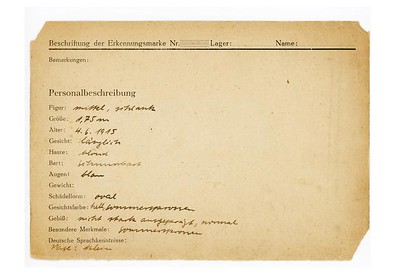

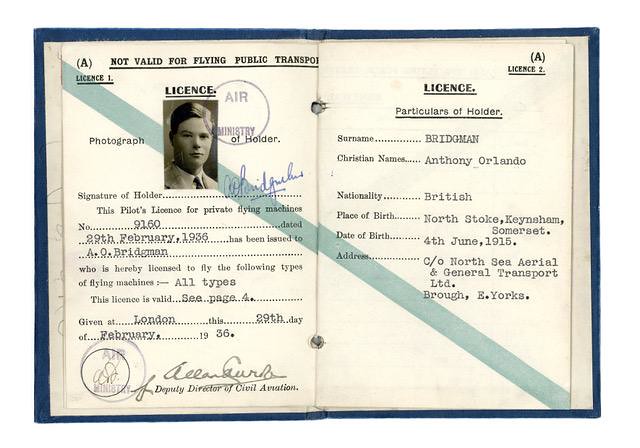

On 29th February 1936 (obviously a Leap Year!) Tony, who was already a qualified service pilot of course, gained his Private Pilot’s Licence, No. 9160, after passing the necessary ground exam and a short flying assessment at Brough in East Yorkshire. This is borne out by the address given on his licence; “c/o North Sea Aerial and General Transport Ltd. Brough, East Yorkshire”. North Sea Aerial and General was in fact wholly owned by Blackburn Aircraft Ltd, who had a factory and airfield at Brough. They provided flying training there for RAF and RAFVR pilots, under contract to the Air Ministry. Tony probably had their address put on his new licence as he was about to be given his first posting. There would have been no point in using the address of whichever RAF Station he was posted to, as that could change frequently. Given that the RAF was Tony’s home, it would have made sense to have any correspondence relating to this “pleasure flying only” licence, (renewals etc) sent to the address of the training establishment, which was of course a fixed address. Tony could easily contact them if he needed to. He probably felt that having such a licence might well come in handy, especially later, when he left the Air Force. It was and in fact still is, something service pilots often do.

Private Pilots Licence (Image courtesy Judith Costa, via Mitch Peeke)

On 23rd March 1936, he was granted a short service commission as an Acting Pilot Officer On Probation in the RAF. On 27th January 1937, 37667 Bridgman, Anthony O; was commissioned as a fully fledged Pilot Officer and posted to 2 Group, Bomber Command. He was sent to 83 Squadron, a day bomber unit then equipped with Hawker Hinds, that was still in the process of being re-formed in their native Scotland; at Turnhouse, near Edinburgh.

83 Squadron was originally formed at Montrose on 7th January, 1917. They were formed as a night bomber unit in the Royal Flying Corps and equipped with the Royal Aircraft Factory’s FE2b and FE2d. After training, the squadron moved to France in March of 1918 and quickly specialised in attacking railway targets, as well as performing vital reconnaissance duties. On April 1st 1918, the RFC was merged with the RNAS to form the Royal Air Force. The motto of what was now 83 Squadron RAF, was “Strike to Defend” and the squadron crest features the Red Deer’s antler, due to the squadron’s connection with Scotland. The antler emblem has six points, which commemorates one outstanding occasion during WW1, when six DFC’s were awarded for one extremely crucial reconnaissance operation. It was an operation that was successfully completed by six individuals in three aircraft on 14/15th June 1918. Those three aircraft from 83 Squadron were the only Allied aircraft flying; the weather having grounded all others. The antler is outlined in black, which refers to their night flying role. After WW1, 83 Squadron was disbanded; on the last day of 1919. Now, in 1937, it was being re-formed; due to the RAF’s expansion programme.

83 Squadron Crest. (Photo IBCC digital archive, by kind permission).

Upon arrival at Turnhouse, Tony met a group of fellow officers who, over the next four years, were to become more than just squadron mates or friends. Outside of his siblings, the RAF was probably the nearest thing to a family that he now had. Among those he struck up a close friendship with at Turnhouse was Jamie Pitcairn-Hill. Upon introduction, it was a popular RAF practice to be given a nickname, usually based on one’s real name. Jamie’s nickname was “Pit”.

F/L Jamie Pitcairn-Hill (Photo: Patrick Otter by kind permission).

A regular officer, graduate of Halton and then Cranwell and above all, a true Scot; Jamie had played Rugby for the RAF. Asked what the “O” in Anthony O. Bridgman stood for, Tony smiled and said; “Oscar”. But Tony had simply used the code word for the letter O in the phonetic alphabet and for one very simple reason: In reality, the “O” was for “Orlando”; after Sir Orlando Bridgeman. It seems to have been a popular choice for the middle name of boys whose last name was Bridgman/Bridgeman in those days. Either way, it was a name that Tony had disliked intensely from day one. Nobody in the mess questioned his phonetically coded statement and thereafter, Tony was always referred to as “Oscar” Bridgman. Many believed that it really was his middle name.

In April of 1937, another junior officer arrived to join the mess at Turnhouse. Acting Pilot Officer John Collier. Tony, Jamie and John quickly formed a close friendship. John’s nickname had come with him, it was “Joe”.

Flight Lieutenant John Joe Collier (Photo Ringwood and Verwood Rround Table via Mitch Peeke)

With flying their two-seater Hawker Hind biplanes on cross-country flights, formation practice or else dive-bombing practice in the Firth of Forth; then re-living the day’s events in the convivial atmosphere of the mess after dinner, squadron life was pretty easy-going in those days. John Collier later recalled in his memoirs that if you were selected to perform the ground based task of Range Officer during bombing practice, it was pretty much a sunny day by the sea, (albeit with a pair of binoculars, a pen and a score sheet), that you were in for. A hardship indeed!

The Pilots not only formed great bonds with each other, but also with their ground crews and Air Gunners, too; all of whom they relied upon. Pilots often took members of their ground crew up on pleasure flights around the immediate locale and this greatly helped to engender a deep pride in “their aircraft” and “their man” in the ground crews.

On 12th May 1937, not long after John Collier had arrived, the coronation of King George VI was taking place in London. Tony and John somehow managed to wangle last-minute permission (and a three-day pass!) from their C.O, to attend. Dashing off to London, they took in a bit of a detour to RAF Upper Heyford, there to collect one of John’s friends; the dashingly Bohemian, half English/half German Count Manfred Beckett Czernin. (Manfred would later distinguish himself as an RAF Fighter Pilot, particularly during the Battle of Britain).

The three arrived in London in time to be too late for the main event, probably due to their detour, and realized to their horror that in their haste to leave, nobody had thought to bring much in the way of cash! Undeterred, the three officers duly called on Count Czernin’s Mother, obtained the necessary funds and then went out to find a suitable party to invite themselves to! It didn’t take them long to find one and a thoroughly decent time was had by all! Oh, and the new King was crowned as well, apparently!

The start of Tony and Guy.

Guy Gibson VC as Wing Commander 1944. The photo was taken shortly before his death (Photo: IWM CH13618 Crown Copyright expired).

In September of 1937, yet another junior officer arrived at Turnhouse to join their ranks. Acting Pilot Officer Guy Gibson. He was assigned to the care and tutelage of Pilot Officer Tony Bridgman, in A Flight, but when Gibson arrived, he already had something of a blot on his copybook: A for Attitude.

The young Guy Gibson has been described as being something of “an acquired taste”. Gibson came from a remarkably similar family background as Tony had, but where Tony’s parents had been distinctly distant, Gibson’s parents had added a further dimension to distant parenting. Like Tony, Gibson was born to Colonial parents in India, but his Mother and Father separated when he was just six. His Mother took the children and returned to England, but sadly she also took to drinking and became increasingly abusive and bullying toward her children. As she descended into alcoholism, her treatment of her children worsened and Guy was more or less taken into care via his school. It may have been this factor that had led the young Gibson to adopt a very condescending attitude toward his ground crews.

In the Officer’s Mess, he was called “Gibbo” and despite his perhaps being an acquired taste, Tony, Jamie and John happily accepted Guy into their circle of friendship. It would fall principally to Tony, as Gibson’s supervising officer, to smooth off the rather immature Gibson’s rough edges.

At the end of June 1937, John Collier was promoted to Full Pilot Officer and 83 Squadron got a new CO. Squadron Leader Leonard Snaith, a former member of the victorious 1931 Schneider Trophy Team, had arrived to take up command. The pilots of 83 Squadron felt justly proud of their new CO.

On 16th November 1937, Guy Gibson was also promoted to the rank of Full Pilot Officer. This elevation in status and responsibility though, did little to curb his attitude toward the lower ranks. He could still be pretty obnoxious, to his ground crews in particular, and there was still little sign that his attitude toward them was changing. Though known as “Gibbo” to his fellow officers, Gibson was now known to his ground crews as “the Bumptious Bastard”. This was something that could not be allowed to continue and changes were coming.

Nothing much changed immediately, though. During the Winter of 1937/38, the squadron practised attacking such vitally important targets as Tilbury Docks and Worthy Down. A “bracing” practice to say the least, dressed up as they were, very much like their RFC predecessors and flying an equally antiquated, open cockpit biplane. As the Spring of 1938 came, so too did a slow-growing tension with Hitler’s New Germany.

Changes.

On 14th March, 1938, the first big change came. The squadron “upped sticks” from 2 Group and Turnhouse and moved South, to RAF Scampton in Lincolnshire. They were now part of 5 Group, Bomber Command and were sharing Scampton with 49 Squadron. Soon, they would also be saying goodbye to their Hawker Hinds as 83 Squadron, like their comrades of 49 Squadron, were about to be modernised. Between March and May of 1938, Pilots, Air Gunners and ground crews were all sent off in batches to different stations for armaments, technical, gunnery and other courses. All books, cramming for exams and no flying!

On 20th May 1938, Tony was made Acting Flying Officer and on 27th August that same year, having proved his worth, he was duly promoted to the rank of Flying Officer. He was also now the Acting Flight Commander of A Flight. His friend John Collier was made Acting Flight Commander of B Flight. 83 Squadron were gearing up for war.

However, the tensions with Hitler were seemingly resolved that September by the Munich Agreement. “Peace for our time” declared a jubilant Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, as he stepped off the Imperial Airways airliner at London’s Croydon Airport. But it was an uneasy peace, obtained at the betrayal of Czechoslovakia, that Chamberlain had in fact won.

With the political tensions eased, at least for now, the Pilots started their aircraft conversion courses. They converted onto the Bristol Blenheim to start with, as 83 Squadron were going to be re-equipped with the new Handley-Page Hampden; a (fairly) fast, twin engined, monoplane medium bomber carrying a crew of four, soon to be dubbed “The Flying Suitcase” by its crews.

The Flying Suitcase

The Hampden was a rather peculiar aircraft. It was designed by a German, Gustav Lachmann. It was very long and slim, much like the German Dornier 17, in the crew section particularly. The Hampden had a maximum speed of 260mph, a theoretical maximum bomb load of 4,000lbs and carried a crew of four.

Internally, the aircraft was rather cramped, being only about three feet wide. Up front, on the lower part of the stepped deck, with his own personal entrance/exit, was the Navigator/Bomb Aimer. Aft on the lower section, also with his own personal entrance/exit, was the aft-facing Ventral gunner. Between these two crew positions, was the aircraft’s Bomb bay.

On the upper stepped level of the deck sat the Pilot, with the aft-facing Wireless Operator/Dorsal gunner some ten feet or so behind him. Boarding the aircraft, the Wireless Operator/Dorsal gunner had to climb in first, much in the manner of a Fighter Pilot; up onto the wing (via a ground crew ladder) then climb in through the pilot’s sliding canopy to clamber through to his position. Once inside, it was his job to fold the back of the pilot’s seat up, so that the pilot could then clamber aboard in the same fashion to take his seat in the cockpit.

Pilot’s cockpit of the Handley Page Hampden (Photo: IWM CH1207. Crown copyright expired).

The pilot’s cockpit (or “Office” as it was usually called) was a very busy place. He had literally every control for the aircraft in front of and around him. There was also a fixed, forward firing gun which, (if he had any spare time!) the pilot could use. Moving about inside the cramped interior of a Hampden with a parachute strapped on, was practically impossible. Trying to get out of a Hampden in an emergency, frankly; didn’t bear thinking about too much.

In October, once conversion training was completed, the new aircraft had to be collected from the factory by their crews and flown back to Scampton. Thereafter, a friendly rivalry began to develop, not only between 49 Squadron and 83 Squadron, but also between A Flight and B Flight of 83 Squadron; in everything from flying prowess to drunken partying!

As Gibson later recalled in Enemy Coast Ahead, they were “forever putting it across B Flight.” Hi-Jinks in the Mess, pranks, drinking games, but above all; flying. With John Collier in B Flight, and Tony Bridgman, Jamie Pitcairn-Hill and Guy Gibson in A Flight, Tony began surreptitiously using this inter-Flight rivalry to smooth out some of Gibson’s less admirable traits. Gibson was competitive to say the least and it was this trait that Tony tapped into. In flying, Tony first began nurturing Gibson’s considerable piloting skills, by supplementing them with his own. He was sharpening and focusing Gibson’s daring side, yet carefully imbuing in his protogee a sense of respect for his crews, both Air and Ground. Having achieved that aim, he started pushing Gibson little by little as a pilot, by making Gibson compete with him, in a “anything you can do, I can do better”, style.

The Hampden, never the most beautiful of aeroplanes, was still something quite new, revolutionary almost, for pilots who were used to biplanes. For a twin-engined bomber type, the Hampden could almost be flown like a fighter, if you were a good enough pilot; which Tony knew of course, was something that Gibson was just so itching to prove that he was. Flying the Hampden in such a manner was something that both of them would later prove was quite possible.

Tony often said that he’d always felt Gibson wanted to be famous for something and Gibson himself made no secret of the fact that he wanted to win a VC, somehow. The friendly rivalry between A Flight and B Flight not only greatly strengthened the camaraderie of each Flight and the bond between the four friends at the head of it, but also helped to firmly bolster the brotherhood of the squadron’s officers. Flying hard together, training hard together and partying hard together, theirs was a fraternity that each would come to rely on over the coming two years, as the clouds of war were ominously forming for all to see. On August 31st 1939, telegrams were sent out to all officers on leave: “Return to unit immediately”.

War!

The balloon finally went up on Sunday 3rd September 1939; as with a heavy, leaden tone, Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain announced to the nation over the wireless, that Britain was once more at war with Germany. The “World’s Best Flying Club” was suddenly forced to closed its peacetime doors and that hitherto carefree life now came to an abrupt end. Flying Officer Tony Bridgman and 83 Squadron would be in action from day one of the conflict.

That Sunday morning of 3rd September 1939, saw the boys of A Flight gathered in their Flight Commander’s office. Guy Gibson gave a wonderful description of that momentous morning, not only of the setting but also of his Flight Commander; Tony Bridgman, in Enemy Coast Ahead. They had just finished their morning Tea, which had been brought to them by a girl from the NAAFI, and the room was full of palpable tension and cigarette smoke.

“There Oscar Bridgman, the Flight Commander, sat with his hat to the back of his head, his feet up on the table and his chair looking liable to fall over backwards at any minute. He was a tremendous character was Oscar. He had a quick temper, but could fly as well as any man. I could never wish for a better Flight Commander and we were all right behind him”. In reading those and his next few sentences, one is acutely struck by the maturity of his attitude and the reverence with which he described not only Tony. There were others present that Gibson noted: “…Mulligan and Ross (we used to call them Mull and Rossy), two Australian boys who joined us back in 1937. They did practically everything together. Sometimes they would have long heated arguments which were the amusement of the whole Flight.”

However, it is his next paragraph that is perhaps the most telling. Gibson recalled that the Flight Sergeant in charge of maintenance (known to one and all as “Chiefy”) came in to report that all aircraft were ready for flight testing. Gibson continues: “Great fellow was F/Sgt Langford…I could write a lot about the ground crews. They are wonderful men and do a really hard job of work for very little pay; only their pride in their squadrons keeping them going.” So wrote Wing Commander Guy Gibson in the Winter of 1943/44. The “Bumptious Bastard” was by then no more; and that was very largely due to Tony Bridgman’s influence and leadership. In fact, it would not be long at all before Gibson would be taking care to nurture his own crews, just as Tony had shown him, by example.

With Chamberlain’s announcement over, Tony inhaled his cigarette deeply, then blew the smoke out through his nose. Turning to his assembled Flight, he said: “Well, boys, this is it. You’d better all pop out and test your aeroplanes. Be back in half an hour’s time. There will probably be a job for you to do.” As it turned out, there wasn’t. After flight testing, the crews all had lunch. They were all called to the lecture hall over the Tannoy, but it was for a brief talk from the Station Commander about the situation. It was the next day that the squadron was called to action.

Tony with P/O Powell. Taken at Scampton in 1939 (Photo courtesy of Frances Leach).

On that first day proper of the war, confusion was rife. People were seeing enemy aircraft where there were none and the same went for enemy warships. 83 squadron were required to provide six aircraft; three from A Flight and three from B Flight. As Squadron Leader Snaith was going to lead the raid himself, his Senior Flight Commander; Tony Bridgman, would be remaining on the ground. His job would be holding the Fort or leading if another operation was required whilst Snaith and Co were out on this one.

Snaith chalked up the two other crews from A Flight as being those of Rossy and Gibbo. Joe Collier would lead the three from B Flight. Each aircraft was armed with four 500lb bombs with the fuzes set at eleven and a half seconds delay. “So we can come in pretty low”, Snaith told them. The targets were possible German Battleships anchored in Schillig Roads at the entrance to the Kiel Canal. Snaith continued: “If by chance there are no Battleships there, you may bomb the ammunition depot at Marienhof, but under NO circumstances are you to bomb civilian areas or houses”. Initially, this was to be a gentlemanly war, it seemed. Take off was at 15:30, the weather was expected to be bad with low cloud and they were told to watch out for balloon cables. The balloons themselves would be hidden in the clouds. Prime target was the Battleship Admiral Scheer. If she was there.

In the event, the sortie was a washout. All they found was a lot of very low cloud, a choppy and murky-looking sea and fast fading light. No Admiral Scheer, in fact no warships of any kind. Disappointed yet possibly slightly relieved, they brought their bombs back to Scampton.

What followed now was a long period of ennui. The Autumn weather soon arrived and militarily, nothing much was happening. The period known as “The Phoney War” to the British and “Sitzkrieg” to the Germans, had set in. 83 Squadron contented themselves with further training, including night flying. They may not necessarily have welcomed it, but in truth, they needed it.

On 3rd December 1939, three months exactly since the outbreak of war, Tony was promoted to the rank of Flight Lieutenant and was now the actual senior Flight Commander, not the acting one. There was excitement later that month when someone had evidently started seeing German warships again. This time it was the Lutzow they were sent forth to hunt. Taking off at short notice, the squadron raced out to sea; North-east, toward the Norwegian coast. Nearly eight hours later, they returned having yet again seen nothing but a great expanse of grey sea, grey cloud and their own breath condensing inside their frigid aircraft. Handley-Page it seemed, had not deemed an internal heating system to be necessary for the Hampden’s crew compartments. Either that or they’d simply left themselves with no room to install it!

The only other bit of excitement for the squadron was when John “Joe” Collier got married on 30th December, to his fiancée of two months; Miss Elizabeth Julia Bishop. Collier’s best man was Jamie Pitcairn-Hill. It was perhaps somewhere around this time that Tony had started seeing Elizabeth’s sister; Virginia.

The Winter of 1939/40 was a harsh one with heavy snowfalls. Not much good for flying. In the meantime, improvements such as armour plating and self-sealing fuel tanks were being fitted to the Hampdens. Still no crew heating though!

With so much in the way of bad weather keeping both of Scampton’s squadrons grounded, the older officers on the base, some of whom had seen action in WW1, did what they used to do back then: Gather round the piano and sing songs. There were the old favourites such as The Bold Aviator, I don’t want to join the Air Force and of course newer songs like He had to go and Prang her in the Hangar and The Flamin’ Firth o’ Flamin’ Forth. With 83 and 49 Squadrons both having their roots in the RFC, each had their own “War Cry”, too. With battle lines drawn from each end of the Mess, and trying to outdo each other for sheer volume: “Up the Forty-Ninth!” and “It’s not Eigh-ty-one, it’s not Eigh-ty-two; It’s EIGHT-TEE THREEE!” was loudly chanted by each beer-fuelled squadron’s officers, before they all “sallied forth” into the fray, hell-bent on the “de-bagging” of their respective opponents!

In his book, Guy Gibson recalls one, though somewhat less livelier, evening in the middle of January. “One night Oscar Bridgman came howling with laughter into the Mess. It was unlike Oscar to howl with laughter, so we asked him what was wrong. He could hardly speak. ‘Go into the Billiard-Room’ he said, ‘and see what I have seen’. Quickly we went along, and there a sight met our eyes that made us almost collapse. Three Padres were sitting solemnly around a piano, each with a glass of beer in his hand, each one looking very serious. They were singing ‘Here’s to the next one to die’ !”

With the weather abating, training resumed in February. Blind flying using radio beams was included. This was not exactly “new” as the system was the commercial pre-war German Lorenz System for blind approach and landing, but it was useful.

Spot of Gardening, anyone?!

As the Spring came, both 49 and 83 Squadrons turned to Gardening when the weather permitted. No, they hadn’t all developed green fingers with the Phoney War’s boredom. “Gardening” was the code name for a fairly dangerous pastime; one which both squadrons would become specialists in.

The “Back Room Boys” or “Boffins” as they were usually known, had been very busy refining the design of a new German, Air-dropped Magnetic Mine. One had kindly made itself available by obligingly washing up on a beach and after some brave soul had successfully managed to defuse the Hadean device, it was taken away to be thoroughly investigated. Not only did the Scientists quickly come up with a counter measure, they greatly refined the mine itself and the RAF now took on the job of returning the favour to the Germans.

The refined British version weighed in at 1,700lbs; just under half of the Hampden’s absolute maximum load, but the mines were physically rather large so each aircraft could only carry one of them. The mine had to be planted accurately and its position marked on a chart. It also had to be dropped from very low altitude on a parachute, to ensure the accuracy of its placement, in areas known to be shipping lanes in and out of enemy harbours. Each mine was referred to as a “Vegetable” and each area was called a “Garden”. In turn, each Garden had its own code name, such as “Carrot” or “Cabbage”. Even flower names were used, such as “Daffodil” or “Hollyhock”.

With the sudden German invasion of Denmark and Norway, 83 Squadron started “Planting” their vegetables in gardens such as the Baltic approaches to Kiel or Harbour entrances on the Danish Coast. Anything to disrupt enemy shipping, Naval or Merchant. At that time, there really wasn’t any kind of overall bombing strategy in place. The type of operations were decided at Group level but the details of who, when and where, were decided at Squadron level. On Chamberlain’s order, non-military targets were strictly off limits. The phrase “There must be no danger of hitting Private Property” became an RAF euphemism for “not killing civilians”.

So, with nothing much in the way of detailed operational orders coming down from “on high”, it was quite common for Pilots to “go off and do a spot of gardening”. Pilots planned their own routes, take off times, etc. They filed their flight plans and if there were no objections, off they went. 83 Squadron’s monthly Operations Record Books start to feature such operations from around the last days of March 1940. Comments such as “Four aircraft detailed for Gardening operations. Carrot successfully planted. All aircraft returned safely” almost begin to appear routinely thereafter.

Section of one of Tony’s RAF escape maps. Designed to be sewn into the lining of aircrew Flying Jackets, these maps were printed on incredibly thin, silk-reinforced paper. They were issued to aircrew operating over enemy territory in case they were shot down (Courtesy Judy Costa).

With Sweden being neutral, a lot of pilots on gardening trips would cross the North Sea and turn onto the heading for their dropping run, by finding a suitable Swedish landmark to go from. The Swedish coast was lit up like a Christmas Tree, which made their job a lot easier. Initially, the Germans didn’t seem to realize exactly what these nocturnal low-flying singleton aircraft were up to either, presumably because they seemed to be coming from neutral Sweden. It wasn’t till later, as France was falling, that the Germans; rather un-sportingly it was felt, deployed Flak ships out in the Roads.

Occasionally though, the weather over the garden prevented planting. In which case, the pilots were under strict instructions to bring their vegetable back or to dump it well out into deep water. Under NO circumstances was one of those mines to be allowed to fall into enemy hands. As far as was known, the Germans hadn’t realized that the British knew about their new magnetic mine, let alone that they had devised a counter measure to it and refined the design. Any successes the British sown mines were known to have had were never made public either, for the same reasons.

In between sorties, squadron life now tended to consist of horseplay, drinking and high jinks. Guy Gibson’s book is laced with rich stories of such capers, which usually occurred as a result of Tony Bridgman “taking over” a pub and getting Gibson to drive them all there, with far too many people crammed into his car!

Gardening however, was not the only type of operation that 83 Squadron undertook. “Ploughing” was another. This was a low-level, hit-and-run strike. A sneak attack, where the objective was to “Plough the field, then scatter”! It was one such raid that would win Tony Bridgman his DFC.

Sources and Acknowledgements (Part 1):

Frances Leach (Tony Bridgman’s middle Daughter).

www.rafcommands.com/archive

Howard Eastcott, for locating Frances Leach and for some background information on Tony.

http://www.mcsoxford.org/history Modern website of Tony’s old school.

The Authorised Biography of Group Captain John “Joe” Collier. By Simon Gooch.

Enemy Coast Ahead. By Wing Commander Guy Gibson.

National Archives; No 83 Squadron, Operations Record Books, February, March and April 1940.

www.warfactory.com Specs for the Handley-Page HP52 Hampden Mk 1.

The Airman’s Song Book by C. H. Ward-Jackson. Published 1945.

Most Secret War by Professor R V Jones.

David Costa. (Husband of Judith, Tony Bridgman’s eldest Daughter).

Letters to Tony Bridgman from Dr G. Pearson.