The American Air force played a major part in our aviation heritage. During the war many thousands of aircraft, took off from airfields around the Eastern Region. Many never came home. These places have left an indomitable mark on not only our landscape, but the hearts of those they touched whilst here.

In Trail 6 we visit six former World War Two airfields, each one being a major base used by American forces during the 1940s. One of these was a late opener, and housed a brand new Bomb Group fresh out of training, who were thrust into the war during the combined ‘Big Week‘ campaign against the German aircraft industry in February 1944. It is this airfield that we visit first. Located just off the main A1 road, it remains an active airfield today, although the roar of the Wright Cyclone engines have been replaced by much smaller and more sedate single engined aircraft. We start off at RAF Glatton, otherwise known as Station 130.

RAF Glatton (Conington) Station 130.

Built by the 809th and 862nd Engineer Battalion (Aviation) of the U.S. Army in the last months of 1942, Glatton was unique in that it was constructed around a farm that remained in situ throughout the war. The owner moved out as the airfield was built with the site returning to agricultural use after the Americans left. Built as a Class A airfield, it had the standard 3 runways; one of 2,000 yards and two of 1,400 yards, whose surface construction was of tarmac and wood chip. The apex of the ‘A’ pointed easterly with the main runway running west to east. To the north-west of the site lay the bomb store, a traditional site consisting of Pyrotechnic stores (x4), incendiary stores (x10), small bomb container stores, fuzing points and component stores amongst others.

Around the perimeter track were forty-three spectacle and six frying pan style hardstands for aircraft dispersal. Unusually, the perimeter track split to the west side of the airfield, which meant that aircraft movement encircled both the technical area and main administration site. It is here, to the west of the main airfield site, that the majority of the aircraft dispersal pans were found. The other section of this track wound round the front of this area allowing for uninterrupted views across the main airfield and its runways.

Glatton was also constructed with two type T2 hangars, both built to the 1941 design drawing No: 3653/41, with one being located to the eastern side, and the other to the western side, in the main technical area of the airfield.

To the northern side of the airfield lies the small village of Holme, and to the south the hamlet of Conington. The airfield’s name however, Glatton, came from yet another village some 4 miles away to the west; the reason ‘Glatton’ was used and not ‘Conington’ being due to the very similar RAF Coningsby not far away in Lincolnshire.

It was to the south-west of the airfield that the dispersed accommodation sites were located. Site 2, a communal site, included a barbers and shoemakers shop; Site 3, the mess, included a dining room and cooking facilities for 1,200 people; Site 4, a second mess site; Sites 5 and 6 (RAF sites) airmen’s barracks and sergeants’ quarters; Sites 7, 8 and 9 were Officers’ quarters with associated drying rooms and ablutions; Site 10 another sergeants’ site; Sites 11 and 12 were the WAAFs’ site with a hairdressers, small sick quarters, recreation room and officers’ quarters; Site 13 the main sick quarters and lastly Site 14, the sewage disposal site. The majority of the huts found on the site were Nissen, built to standard 1941 / 42 designs. All in all, the airfield could accommodate around 3,000 men and women of mixed rank.

These accommodation huts, with their cement floors and iron roofs, were cold and lacking any comforts at all, double bunks were provided for the enlisted men with slightly more space for Officers, but they all had minimal locker room or private space. Here, like many air bases in wartime Britain, new crews were largely ignored, friendships were not forged for fear of losing them on the next mission. As a result, many on these bases did not know other crews outside of their own huts, instead choosing to spend every minute with their own crew – the heartache of losing good friends being too painful to bear on a daily basis.

Used primarily by the US Eighth Air Force, Glatton was opened in 1943 and designated Station 130, home to the 457th Bomb Group, U.S. Eighth Air Force.

Composed of the: 748th, 749th, 750th, and 751st Bomb Squadrons, it was assigned to the 94th Combat Bombardment Wing (joining both the 351st and 401st BG) of the 1st Bombardment Division. Its aircraft, B-17G ‘Flying Fortresses’, flew throughout hostilities with the tail code a black ‘U’ on a white triangle, reversed in an Air Force restructuring during the winter of 1944/45 with a blue diagonal added to the fin.

The 457th’s journey to war began on May 19th, 1943 (the same time as the Trident Conference which led to a re-organisation of the USAAF in Europe), with activation that summer at Geiger Field, Washington. Being formed so late in the war, the 457th would be a short-lived group, but they were none-the-less still involved in some of the most ferocious air battles of the Second World War.

After training at Rapid City Airfield in South Dakota, they moved to Ephrata Army Air Base, one of the United States’s largest training bases, then onto Wendover Field in Utah before their final departure to the United Kingdom and Glatton airbase.

The 457th entry to the war would be a real baptism of fire. On Monday 21st February 1944, the combined forces of the USAAF and the RAF were involved in the ‘Big Week‘ campaign. Officially known as Operation ‘Argument‘, it was designed to smash the German aircraft industry in one fell swoop. Postponed repeatedly from early January due to bad weather, it finally began on the night of February 19th 1944, with US air forces flying their first operations on the 20th.

Two days into ‘Big Week‘ the 457th were dispatched along with 335 other B-17s of the 1st Bomb Division (BD) to attack Gutersloh, Lippstadt and Weri airfields, but having no pathfinder aircraft and in poor weather, they had to turn to targets of opportunity. With the 2nd and 3rd BDs also in operation that day, some 860 heavy American bombers filled the skies over Germany.

With poor results and difficulty in forming up, this initial mission was further marred by the group’s first loss; that of B-17G #42-31596 piloted Lt. Llewellyn G. Bredeson, of the 750th BS. Flying their first mission, and in the unenviable position of ‘tail-end-Charlie’, they were singled out for a prolonged and devastating attack. Two engines were hit and substantial damaged was caused to the aircraft, including its oxygen system, in attacks which left the tail gunner seriously injured. Lt. Bredeson gave the order to bale out, an order that included the injured tail gunner. The other crewmen, tethered him to the aircraft by his static line, and then pushed him out so that his parachute would release automatically. After the stricken bomber was vacated, it crashed four miles west of Quackenbruck in northern Germany, one of the gunners, Sgt William H. Schenkel, dying from his injuries whilst the remainder of the crew were captured becoming prisoners of war.

The next day (22nd) the 457th were back in action, with more ‘Big Week‘ attacks. This time there were no losses for the group, a reassuring mission that was followed by a day’s break from flying. On the 24th, they joined with other 1st Bomb Division groups attacking Schweinfurt, a target that struck fear into the hearts of American airmen. This mission, Mission 3 for the 457th and Mission 233 for the USAAF, would be the return to the ball bearing plants, a product that without which, the German war machine would literally grind to a halt.

In the original attack on 17th August 1943, a combined offensive against Schweinfurt and Regensburg saw a 19% loss rate, some sixty bombers from 315 that were sent out. It was no wonder the target’s name struck fear into the hearts of the new group.

The 1st BD were the only group sent to Schweinfurt that day. The 3rd and 2nd attacking targets elsewhere in Germany. The 457th sent eighteen aircraft, part of a force of 265 B-17s. As well as dropping 401 Tonnes of high explosive bombs and 172 Tonnes of incendiary bombs, they also dropped just short of 4 million propaganda leaflets.

The defensive ring around the city had not weakened, if anything it had been strengthened since its previous attacks, flak was heavy and accurate and fighters were abundant. Some 110 US airmen were classed as ‘Missing in Action’ that day, but luckily for the 457th, only one aircraft was lost. Douglas-Long Beach built B-17G #42-38060 of the 750th BS, was hit by flak, the #1 and #2 engines were put out of action, and #3 and #4 began over revving – the crew unable to control them.

With the navigator, 2nd Lt. Daren McIntyre badly wounded and the Right Waist Gunner Sgt. Italo Stella killed when flak pierced his flak jacket; the pilot, 2nd Lt. Max Morrow decided the best option was to crash land the aircraft and hope that in doing so, they would all survive. After carrying out a wheels-up belly landing near to Giessen in Germany, the aircraft was surrounded by locals, who removed the dead and wounded from the aircraft wreckage. Fearing for their lives, the immediate future looked bleak for the crew. Eventually German officials intervened, and the survivors were taken to POW camps where they stayed for the remainder of the war. 2nd Lt. McIntyre sadly later died, succumbing to his severe wounds.*2

The 457th’s final mission for ‘Big Week‘ occurred on the 25th, a mission to attack the Messerschmitt factory in Augsberg, Bavaria. On this day they lost two more aircraft: #42-97457 (six killed the remainder POWs) and #42-31517 (Seven killed the remainder either evading capture or taken as POWs). Of the twenty-four aircraft that took part in this mission, all but one suffered battle damage to a various degree. The first week had not been disastrous, but it had nonetheless, been a very difficult week for the men of the 457th.

Following the February campaign, the 457th would go on to drop both leaflets and bombs on coastal targets and more prestige targets including Wilhelmshaven on March 3rd 1944, and Berlin on March 6th. On this mission, two further aircraft were lost, not by being shot down by flak or enemy fighters, but because one was rammed by a Luftwaffe Me-410 fighter causing it to strike a second B-17 of the same group in the lower section.

Mission 8 for the 457th would take the group consisting of eighteen aircraft to the V.K.F. ball-bearing works in Erkner on the outskirts of Berlin. The factory, a subsidiary of the Swedish S.K.F. ball-bearing company, produced many of the ball-bearings required for the German war machine. B-17G #42-31595 ‘Flying Jenny‘ was struck by the fighter causing it to fall into the lower section of the formation B-17G #42-31627. Only the tail gunner of 627 survived, the remainder being ‘killed in action’*3.

During this period, losses remained remarkably low for the group, possibly due to the many targets they bombed being secondary, or targets of opportunity, a decision forced on the group primarily by bad weather over the primary target area.

March 1944 saw a remarkable and unique visitor to Glatton, one that not only attracted many military visitors to the airfield, but one that lightened the atmosphere amongst the men. A plan had earlier been formed in the United States to send B-29 ‘Superfortresses’ to China in a bid to support the Chinese and to allow the bombing of Japan from Chinese bases. In early 1944 this plan became reality but reliability problems had dogged the B-29’s engines and so major modifications had to be carried before the long flight could begin.

There was a fear that the Germans might attack the aircraft as they were ferried across the Mediterranean, and so a devious plan was set in motion to fool the Germans into thinking that B-29s were to be based in England, ready to be used against German targets. The first part of this rouse was in early March 1944, when YB-29 #41-36963 ‘Hobo Queen‘*8 took off from Salina Airbase in Kansas taking initially the southern route then deviating to the north and heading to Newfoundland. The B-29, piloted by Colonel Frank Cook, then flew across to the UK landing at RAF Glatton. The aircraft remained at Glatton for a short period before visiting both St Mawgan and Bassingbourn, before its final departure to India in April that year. The ruse had been a success. The B-29 certainly was a draw to the crews, its enormous size dwarfing anything hat had been seen at Glatton before, it was truly a remarkable aircraft, the likes of which had never been seen over the Huntingdon countryside previously.

Crews and ground staff swarm around B-29 #41-36963 at Glatton airfield 11th March 1944*4.

On April 22nd 1944, the 457th took part in the famous Mission 311, the mission in which US forces lost more aircraft to enemy intruders than at any other time in the war. On this mission, Hamm – the largest marshalling yard in Germany – was the target. The 457th along with the 401st BG and the 351st BG of the 94th Combat Wing, found themselves arriving last over the target, by which time it was covered in smoke from both previous bombing and German defensive smoke pots. Finding a break in the cloud the 457th dropped their bombs onto the target achieving ‘good’ results. However, by the time the Group were approaching home, it was dark and a group of Luftwaffe fighters had managed to hide themselves within the formations mingling with the bomber stream. By the time their presence was known, it was too late, and a number of aircraft, mainly B-24s, were attacked and either shot down or badly damaged. The 457th were once again lucky, only one aircraft, #42-106985 ‘La Legende‘, was severely damaged, but not to the point that it couldn’t crash-land back at Glatton. Significantly, on-board this aircraft was the station commander Lt. Col. James R. Luper.

B-17G #42-106985 after crash landing at Glatton April 22nd 1944. On board the aircraft was the station Commander Lt. Col James Luper. (@IWM)

It was Lt. Col. Luper who had had the honour of both collecting and naming the 1000th Douglas Long Beach built B-17, (#42-38113), ‘Rene III’, named so after his wife. Initially called ‘Pistol Packing Mama’ by the very people who built the aircraft, she was flown from the United States to Glatton by Lt. Col. Luper and his crew.

Over the next year, ‘Rene III‘ would complete fifty-three missions, many over Germany including: Augsburg, Schweinfurt, Ludwigshafen, Leipzig, Munich, Cologne and Bremen. On her final mission, March 21st, 1945 to Hopsten, she was piloted by Lt. Craig P. Greason (s/n: 0-825840) of the 749th BS.

As the 749th BS aircraft approached the target, ‘Rene III‘ took a direct hit in the wing, close to the No. 4 engine, which caused a fuel leak and subsequent fire. The aircraft then dropped out of formation – one of the worst things that could happen to a stricken bomber. Official records suggest that the B-17 then went on to bomb the target after the fire appeared to extinguish itself. However, the crew were known to have all bailed out safely, after which all the aircrew (apart from Aircraft Engineer Sgt. William Wagner, who was caught and became a POW) managed to evade capture.

The station commander, Lt. Col. Luper, who was not aboard that day, continued to fly with his crew, eventually being lost on 7th October 1944 whilst flying in B-17 #44-8046 on a mission to Politz. Lt. Col. Luper survived a Flak strike on the aircraft and along with 4 other crewmen, was captured and taken prisoner by the Germans. The other six members who were not captured were sadly killed in the attack*6.

The salvage and rescue of damaged aircraft went a long way to supporting the work of the allied Air Forces in Europe. The need to keep aircraft flying meant stripping bits of damaged or scrapped aircraft and reusing them to repair less damaged examples. At Glatton, this went one step further.

B-17 #42-38064 was made into a composite aircraft with an olive drab front end and an aluminium rear; the two fuselage halves being joined at the wing root. The aircraft was named ‘Arf ‘n’ Arf‘, after a popular pub drink at the time made up of half a bitter and half a mild.

The rear of the aircraft came from B-17 #42-32084 ‘Li’l Satan‘ which lost an engine on landing at Glatton after receiving battle damage over Bremen in June 1944, the tail section being salvaged and added to #42-38064.

‘Arf ‘n’ Arf‘ went on to complete several missions, its fate being sealed on November 8th 1944, in a heavy dousing of irony when it collided over the channel with B-17 #44-8418, ‘Bad Time Inc II’. In the collision, in which all the crewmen of ‘Arf ‘n’ Arf‘ were killed, the propellers of 8418 sliced through the fuselage of ‘Arf ‘n’ Arf‘ cutting the aircraft in two. 8418 went on to land ‘safely’ the crew being uninjured.

With the end of the year in sight, many were looking forward to the New Year celebrations and a renewed hope for peace. But New Years day 1945, would be a notable day in the European Air War for other reasons. Not only for the appalling bad weather that had dogged the whole theatre of operations for the entire winter, but also for the fact that the Eighth Air Force Bomb Divisions were re-designated as ‘Air Divisions’. It was also a day where the Luftwaffe launched a series of attacks against allied airfields in the low countries causing widespread damage to aircraft and airfields.

Glatton’s 457th continued the battle, returning to skies over Germany once more. This time they were assigned to the oil refinery at Derben, an industrial target sitting on the banks of the Elbe to the west of Berlin. A massed and concentrated attack, it saw all the 1st Air Division in operation along with both the 2nd and 3rd Air Divisions. In all 850 B-17s and B-24s were launched that winter’s day. With cloud covering large parts of the continent, targets were difficult to find, the Group had to deviate from both its primary and secondary targets, as neither could be seen for visual bombing. Instead Kassel was chosen as a target of opportunity, and the bomb run made. Again, cloud covered much of the area, but the target itself was found to be clear and so the formation followed a Pathfinder force and bombed on their markers.

Whilst Flak was light, it was considered accurate, with fourteen aircraft being damaged, but thankfully there were no 457th losses that day, and all crews returned to Glatton safely. It was during this mission that B-17 #42-38021 “Mission Maid” achieved her seventy-fifth mission, a remarkable achievement for any heavy bomber of the Second World War. In February she would be forced down onto French soil, after which she was declared ‘War Weary’ and transferred No. 5 SAD where she was modified to carry lifeboats. In July 1945 she was then transferred to the United States where she was sold for scrap metal. During her operational life ‘Mission Maid‘ was credited with the downing of eight enemy aircraft – a sad end to a glorious career.

The cold winter of 1944 / 45 also saw the German’s last-ditch effort to defeat the allied forces on the ground. With a massed counter attack through the Ardennes forests in what became famously called the ‘Battle of the Bulge’, the Germans surrounded the town of Bastogne and the 101st Airborne. The Glatton crews supported the ground troops by attacking resupply lines behind enemy lines, including the numerous failed attempts at the Remagen Bridge.

As the Allies fought their way over the Rhine, the Glatton crews were there in support attacking other targets behind German lines.

On April 20th 1945, the 457th flew their final operational mission, attacking the marshalling yards at Seddin, to the south of Berlin. With the end of the war just around the corner there was little resistance from either ground forces or the Luftwaffe, none of the 457th aircraft taking hits or suffering any damage, it was virtually a ‘milk run’.

Following VE day, the 457th flew POWs back from Europe to England, then with no further action to undertake, the airfield was handed back to the RAF’s No. 3 Group under the control of Bomber Command operating both the Avro Lancaster and Consolidated B-24 Liberators flying out to the Middle East.

By June the war for the 457th was over. The men and machines were transferred back to the United States with the aircraft leaving Glatton between May 19th and 23rd, and the ground echelons sailing on the Queen Elizabeth from Gourock in Scotland, at the end of June. After arriving at New York there was 30 days rest before the men assembled at Sioux Falls. Here the axe fell and the 457th was no more, the four squadrons being disbanded for good and the Group removed from the Air Forces inventory. Glatton was eventually closed and the site was sold off in 1948.

The 50ft high Braithwaite water tower is virtually the only surviving structure at Glatton. Thus stands on the edge of the former Site 7.

The 457th had been short-lived. They had taken part in many of Europe’s major battles, seen action over Normandy, the breakout at St. Lo, supported the Airborne attack on Holland and the crossing over the Rhine into Germany itself. They had bombed many of Germany’s major cities, including the heart of the German Reich, Berlin. In all, the 457th flew 236 missions, dropping 17,000 tons of bombs, and destroying 33 enemy fighters (along with 12 probable and 50 damaged). They lost a total of 83 aircraft to enemy action, with a small number being scrapped following accidents and heavy flak damage.

Glatton quickly returned to agriculture. The vast technical area was demolished, concrete tracks were dug up and buildings removed. Two of the three runways however, remained, and during the 1970s flying activity began to return once more. The main runway was resurfaced, and is now used by the Peterborough Business Airport whilst the second runway remains in its original concrete but unlicensed for any aviation activity. The third runway has been turned into the road that traverses the site, but all other hard tracks have all but gone.

The original control tower was demolished years ago but a new one has been built and flying continues in the form of microlight, helicopter and fixed wing training.

At the nearby All Saints Church in Conington, a memorial stands with the bust of a pilot looking over toward the field as if watching for lost comrades to return, a poignant and moving figure, it has gradually and very sadly begun to look rather unkempt. A further memorial has been erected adjacent to the only substantial building left, a water tower at what was the original entrance to the site next to the main A1 road. This tower now stands as a reminder of the days when B-17s would rumble over the fields on their way to occupied Europe, perhaps never to return. A small display is available in the flying school offices, a reminder to the budding flyers of today of the strong history and heritage of RAF Glatton.

From Glatton, the Trail continues on south. Here we find the second site of this trip, another American air base, that of RAF Kimbolton – home of the 379th BG.

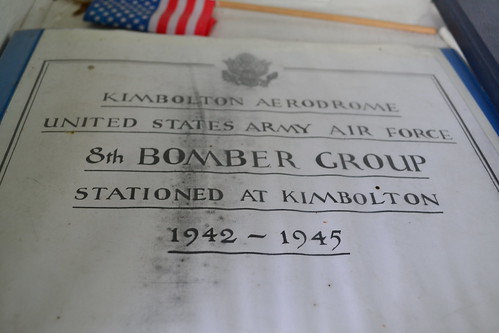

RAF Kimbolton. (Station 117)

We arrive not far from the busy A14 to the south-west of Graffham Water. Perched on top of the hill, as many of these sites are, is Station 117 – Kimbolton. Having a short life, it was home to the 379th Bombardment Group of the Eighth Air Force, flying some 330 missions in B-17s. The site is split in two by the main road which uses part of the original perimeter track for it’s base. To one side is where the runways and dispersal pens would have been, to the other side the main hangers, admin blocks, fuel storage and squadron quarters. The former is now open fields used for agriculture and the later a well-kept and busy industrial site. What was the main runway is crossed by this road where there is now a kart track.

Kimbolton Airfield in 1945, taken by 541 Sqn RAF. (English Heritage RAF Photography – (RAF_106G_UK_635_RP_3217)

Kimbolton was designed with three concrete runways, the main running north-west / south-east, (2154 yds); the second and third running slightly off north-south (1545 yds) and east-west (1407 yds), it also had two T2 hangars with a proposed third, along with 20 ‘loop’ style hardstands and 31 ‘frying pan’ hardstands around its perimeter.

The local railway line formed the northern boundary, the bomb store was to the south-west, the technical and administrative site to the south-east and beyond that the accommodation sites. To house the huge numbers staff to be located at Kimbolton, there were two communal sites; a WAAF site; sick quarters; two sewage sites; two officers quarters, an airmen’s quarters; a sergeants site and two further sites with ablutions and latrines. These were all spread to the south-eastern corner of the airfield,

Originally built in 1941 as a satellite for RAF Molesworth, it was initially used by the RAF’s Wellington IVs, a rare breed where only 220 airframes were built. 460 Sqn were formed out of ‘C’ flight 458 Sqn at Molesworth and used the Wellingtons until August 1942 when they replaced them with the Halifax II. Staying only until January 1942, their departure saw the handing over of both Molesworth and Kimbolton to the USAAF Eighth Air Force and the heavier B-17s. During this time, the airfield was still under construction, and although the majority of the infrastructure was already in place, the perimeter was yet to be completed.

First to arrive was the 91stBG, who only stayed for a month, before moving on to Bassingbourn. A short stay by ground forces preceded extensions to the runways, accommodation and improved facilities. Now Kimbolton was truly ready for a Heavy Bomb Group.

Soon to arrive, was the 379th BG, 41st CW, flying B-17Fs. Activated in November 1942 they arrived at Kimbolton via Scotland, ground forces sailing from New York whilst the crews flew their aircraft from Maine to Prestwick via the northern supply route.

Arriving in April / May, their first mission would be that same month. The 379th would attack prestige targets such as industrial sites, oil refineries, submarine pens and other targets stretching from France and the lowlands to Norway and onto Poland. Targets famed for heavy defences and bitter fighting, they would often see themselves over, Ludwigshafen, Brunswick, Schweinfurt, Leipzig, Meresberg and Gelsenkirchen. They would receive two DUCs for action over Europe including, raids without fighter escort over central Germany on January 11th 1944. They assisted with the allied invasion, the breakout at St. Lo and attacked communication lines at the Battle of the Bulge. They would operate from Kimbolton until after the war’s end, when on 12th June 1945, they began their departure to Casablanca.

Life at Kimbolton was not to be easy and initiation into the war would be harsh. On the first operation, four aircraft were lost, three over the target and one further crashing on return. Three of the crews were to die; a stark warning as to what would come. Their second mission would fair little better. An attack on Wilhelmshaven, saw a further six aircraft lost and heavy casualties amongst the survivors. Things were not going well for the 379th and with further losses, this was to be one of the bloodiest entries into the war for any Eight Air Force Group.

B-17 Flying Fortress (‘FR-C’, 42-38183) “The Lost Angel” of the 379th BG sliding on grass after crash landing, flown by Lieutenant Edmund H Lutz at Kimbolton. (Roger Freeman Collection)

As the air battle progressed, further losses would be the pay off for accurate and determined bombing by the 379th. Flying in close formation as they did, accidents often occurred. On January 30th 1944, 42-3325 “Paddy Gremlin” was hit by bombs from above. Then again, on September 16th 1943, two further aircraft were downed by falling bombs, close formation flying certainly had its dangers.

Some 1 in 6 losses of the USAAF were due to accidents of one form or another. Collisions were another inevitable part of the close formation flying. A number of memorials around the country remember crews who lost their lives whilst flying in close formation. Kimbolton and the 379th were to be no different. On June 19th 1944, two B-17Gs 44-6133 (unnamed) and 42-97942 “Heavenly Body II” crashed over Canvey Island killing all but one of 44-6133 and three of Heavenly Body II. The official verdict stated that the second pilot failed to maintain the correct position whilst in poor visibility, a remarkable feat in any condition let alone poor visibility whilst possibly on instruments alone. (See full details of the terrible accident).

However, not all was bad for the 379th though. Luck was on the side of B-17F, 42-3167, “Ye Olde Pub“, when on December 20th 1943, anti-aircraft fire badly damaged the aircraft whilst over Bremen. The aircraft limping for home, was discovered by Lt. Franz Stigler of JG 27/6. On seeing the aircraft, Stigler escorted the B-17 over the North Sea, whereupon he saluted and departed allowing the B-17 safe passage home where it landed and was scrapped.

A number of prestige visitors were seen at Kimbolton. These included King George VI, Queen Elizabeth, Princess Elizabeth and General Doolittle. One particular and rather rare visitor arrived at Kimbolton on January 8th 1944. A rebuilt Messerschmitt BF-109 stayed here whilst on a familiarisation tour for crews. Shot down over Kent it was rebuilt to flying condition and flown around the country.

Seen in front of a B-17, Messerschmitt BF-109 runs up her engine at Kimbolton, January 8th 1944. (Roger Freeman Collection FRE 4775)

All in all the 379th had a turbulent time. By the time they had left Kimbolton, they had lost a great many crews, but their record was second to none. They flew more sorties than any other Bomb Group of the Eighth Air Force – in excess of 10,000 in 330 missions; dropped around 24,000 tons of ordnance, equating to 2.3 tons per aircraft; pioneered the 12 ship formation that became standard practice in 1944 and had the lowest abortive rate of any group from 1943. Kimbolton was visited by Lieutenant General James Doolittle, and two B-17s held the record of that time “Ol Gappy” and “Birmingham Jewel“, for the most missions at the end of their service. They also had overall, one of the lowest loss rates of all Eighth AF Groups largely due to the high mission rates.

With their departure to Casablanca, the 379th would be the last operational unit to reside at Kimbolton. Post war it was retained by the RAF until sold off in the 1960s, it was returned to agriculture, the many buildings torn down, the runways dug up and crops planted where B-17s once flew.

Kimbolton today is little more than a small industrial estate and farmland. A kart track has been built on the former dispersal of the 534th, and in the clubhouse is a small display of memorabilia.

At the main entrance to the industrial site, is a well-kept memorial. Two flags representing our two nations, stand aside a plaque showing the layout of the field as was, with airfield detail added. Behind this, and almost un-noticeable, is a neat wooden box with a visitors book and a file documenting all those who left from here never to return. There are a considerable number of pages full of names and personal detail – a moving document. One of the B-17 pilots, Lt. Kermit D. Wooldridge, of the 525th Bomb Squadron, 379th Bomb Group, 8th Air Force kept a diary of his 25 raids, and many of the crew members mentioned in the memorial book appear in his diaries. These are currently being published by his daughter, and can be seen at https://sites.google.com/site/ww2pilotsdiary/ They tell of the raids, the crews and detailed events that took place over the skies of occupied Europe from June 29th 1943. I highly recommend reading it.

This is a lovely place to sit (benches are there) and contemplate what must have been a magnificent sight all those years ago. It made me think of the part in the film ‘Memphis Belle’, where the crew were sitting listening to the poetry just prior to departure, how many young men also stood here ‘listening to poetry’. The control tower would have stood almost opposite where you are now, with views across an enormous expanse. Here they would have stood ‘counting them back’. Like everything else, it has gone and the site is now ‘peaceful’.

Kimbolton saw great deal of action in its short life. But if determination and grit were words to associate with any flying unit of the war, the 379th would be high on that list.

From Kimbolton we move away to an airfield that is synonymous with both the first and last bombing raids of the American Air War in Europe. We travel a few miles north, here we find a truly remarkable memorial and an area rich in history. We go to RAF Grafton Underwood.

RAF Grafton Underwood. (Station 106)

Construction of Grafton Underwood began in 1941, originally part of the RAF’s preparation of the soon to be defunct bomber group to be based in this region. But with the birth of the Eighth Air Force on January 28th 1942, it would become the USAAF’s first bomber base, when the 15th Bomber Squadron arrived after sailing on the SS Cathay from the United States.

The original idea for the ‘Mighty Eighth’ was to house a total of some 3,500 aircraft of mixed design in 60 combat groups. Four squadrons would reside at each airfield with each group occupying two airfields, this would require 75 airfields for the bomber units alone. This figure was certainly low and it would increase gradually as the war progressed and demand for bomber aircraft grew.

The terrible attack by the Japanese on Pearl Harbour diverted both attention and crews away from the European Theatre, but in April / May 1942 the build up began and American forces started to arrive in the UK.

With ground staff sailing across the Atlantic and aircrews ferrying their aircraft on the northern route via Iceland, the first plain olive drab B-17Es and Fs of the 97th BG set down on July 6th 1942, two squadrons at Polebrook and two at Grafton Underwood.

The sight of American airmen brought a huge change to life in this quiet part of the countryside. Locals would gather at the fence and stand watching the crews as if they were something strange. But as the war progressed, the Americans would become accepted and form part of everyday life at Grafton Underwood.

Eventually the airfield would be complete and although it would go through development stages, it would remain a massive site covering around 500 acres of land.

A total of thirteen separate accommodation and support sites would be built; two communal; seven officers; a WAAF site; a sick quarters and two sewage treatment sites to cope with upward of 3,000 men and women who were to be based here.

The accommodation was based around an octagonal road design, the centre piece being the ‘Foxy’ cinema in Site 3 the main communal site. Roads from here took the crews away to various sites hidden amongst the trees of the wooded area. All theses site were located east of Site 1, the main airfield itself.

Grafton would have three runways; runway 1 (6,000 ft) running north-east / south-west, runway 2 (5,200 ft) running north-west / south-east and runway three (4,200 ft) running north to south, all concrete enabling the airfield to remain active all year round.

A large bomb store was located to the north-western side of the airfield, served by two access roads, it had both ‘ultra heavy’ and ‘light’ fuzing buildings; with a second store to the north just east of the threshold of runway 1. Thirty-seven ‘pan’ style hardstands and three blocks of four ‘spectacle’ hardstands accommodated dispersed aircraft around the perimeter track. Surprisingly only two hangars were built, both T2 (drg 3653/42) one in the technical area to the east and the second to the south-west.

On May 15th 1942, Grafton officially opened with the arrival of its first detachment. The 15th Bombardment Squadron (Light) arrived without aircraft and had to ‘borrow’ RAF Bostons for training and deployment. As yet there was no official directive, and so crews had little to do other than bed in. The 15th BS remained here until June 9th 1942 whereupon they moved to their new base at RAF Molesworth and began operations in their RAF aircraft supported by experienced RAF crews. This move coincided with the arrival of the main body of the Eighth Air Force on UK soil and the vacancy at Grafton was soon filled with B-17s of the 97th BG (Heavy).

Only activated in February that year, the 97th consisted of four Squadrons: at Polebrook were the 340th BS and the 341st BS, whilst at Grafton were the 342nd BS and the 414th BS. Whilst State side they flew submarine patrols along the US coast, but with clear skies and little in the way of realistic action, the ‘rookie’ crews would be ill prepared for what was about to come.

With the parent airfield at RAF Polebrook providing much of the administration for the crews, it was soon realised that gun crews, navigators, pilots and radio operators were poorly trained for combat situations. Quickly thrown together many could not use their equipment – whether a radio or gun – effectively and so a dramatic period of intense training was initiated. The skies around Grafton and Polebrook, quickly filled with the reverberating sound of the multi-engined bombers.

These early days were to be hazardous for the 97th. On August 1st, B-17 “King Condor” would crash on landing at Grafton Underwood. The aircraft’s brakes failed, it overshot the runway, went through a hedge and hit a lorry killing the driver.

B-17 41-9024 ‘King Condor’ Crash landed August 1st, 1942 pilot Lt Claude Lawrence ran off runway, through hedge and hit a truck, killing driver John Jimmison. (IWM UPL 19654)

On August 9th, the atmosphere at Grafton became electric, as orders for the first mission came through. Unfortunately for the keen and now ‘combat ready’ crews, the English weather changed at the last-minute and the mission was scrubbed. This disappointment was to be repeated again only 3 days later, when further orders came through only to find the weather changing again and the mission being scrubbed once more.

In the intervening days the weather was to play another cruel joke on the group claiming the first major victim of the 97th. A 340th BS B-17E ’41-9098′, crashed into the mountainside at Craig Berwyn, Cadair Berwyn, Wales, killing all 11 crew members. A sad start indeed for the youngsters.

Eventually though the weather calmed and on August 17th 1942, at 15:12, twelve aircraft took off from Polebrook and Grafton and headed south-east over the French coast. Not only was it notable for its historical relevance as Mission 1, but on board one of the B-17s was Major Paul Tibbets who later went on to drop the atom bomb on Hiroshima 3 years later. If this wasn’t enough, a further B-17, ’41-9023′, “Yankee Doodle”, also contained the Commanding General of the Eighth, Ira Eaker, – truly a remarkably important and historical flight indeed.

The 97th would go on to attack numerous targets including airfields, marshalling yards, industrial sites and naval installations before transferring to the Twelfth Air Force and moving away from Grafton to the Mediterranean in November 1942.

There then followed a quiet spell, for Grafton. A short spell between September and December 1942 saw the heavy bombers of the 305th BG reside at Grafton before moving off to Chelveston and another short spell for the heavies of the 96th BG in the latter half of April 1943 whilst on their way to Great Saling in Essex. It wouldn’t be until early June 1943 that Grafton would once again see continuous action over occupied Europe.

Activated at the end of 1942, the 384th BG (formed with the 544th, 545th, 546th and 547th BS) would train for combat with B-17Fs and Gs, move to Grafton via Gowen Field, Idaho, and Wendover Field, Utah, and perform as a major strategic bomber force. Focussing their attacks on airfields, industrial sites and heavy industry deep in the heart of Germany, they would receive a Distinguished Unit Citation (D.U.C) for their action on January 11th 1944. Targets included the high prestige works such as: Cologne, Gelsenkirchen, Halberstadt, Magdeburg and Schweinfurt. They would take part in the ‘Big Week’ attacks in February 1944, support the Normandy invasion, the break out at St. Lo, Eindhoven, the Battle of the Bulge and support the allied advance over the Rhine. A further DUC came on 24th April 1944 when the group led the 41st Wing in the attack against Oberpfaffenkofen airfield and factory. Against overwhelming odds, the group suffered heavy losses but took the fight all the way to the Nazis.

A dramatic photo of B-17 Flying Fortress BK-H, (s/n 42-37781) “Silver Dollar” of the 546th BS, 384th BG as it goes down after losing its tail. (IWM FRE1282)

Just as Grafton had played its part in the opening salvo of American bombings, it was to be a part of the last. On April 25th 1945, the last bombing raids took place over south-east Germany and Czechoslovakia. Mission 968 saw 589 bombers and 486 fighters drop the final salvos of bombs of the war on rail, industrial and airfield targets, shooting down a small number of enemy aircraft including an Arado 234 jet. Last ditch efforts by the remnants of the Luftwaffe claimed 6 bombers and 1 fighter, before the fight was over. After this all remaining missions were propaganda leaflets as bombs were replaced by paper.

Two years after their arrival the 384th departed for France, eventually returning to the US in 1949 and disbandment. Their departure left Grafton quiet, it was retained by the RAF under care and maintenance and then finally in 1959 declared surplus to requirements and sold off.

In the short two years of being at Grafton, the 384th had amassed 9,348 operational sorties, in 314 missions. They dropped 22,415 tons of explosives and lost 159 aircraft for the shooting down of 165 enemy aircraft. They received two Distinguished Unit Citations and over 1000 Distinguished Flying Crosses. A remarkable achievement for any bomb group.

Grafton today is very different to how it was in the mid 1940s. But before you go to the airfield, you must visit the local church. Passing through the village you’ll see a signpost for the church, park here and walk up the short path. Approaching the church, roughly from the East, you see a dark window which is difficult to make out. However, enter the church and look back, you will see the most amazing stained glass window ever, – the vibrant colours strike quite hard. This window commemorates the men and women of the 384th Bombardment Group of the Eighth Air Force who were stationed at here at Grafton Underwood.

Next to it, someone has placed a handwritten note with the picture of a very young man 2nd Lt. Thomas K Kohlhaas and details of the crew of B-17 ‘43-37713’ “Sons o’ Fun”. It states that he, along with 3 others of the crew, were murdered by German civilians after their aircraft was downed by flak on 30th November 1944. This is a very moving and personal place to be and a poignant reminder of what these young men were facing all those years ago.

When you leave the church, look on the wall of the porch and you will see two dedications. These list the location and names of trees, dedicated to the personnel of the Mighty Eighth, that have now replaced the runways on the airfield. Unfortunately these are on private land and for some very odd reason, not accessible.

Leave the church, turn left into the village, following the stream and then turn left up the hill. The memorial is on your right. Like most American memorials of the USAAF, it has the two flags aside the memorial which is well-kept. When I visited, ‘the keeper’ (who has since become a good friend of mine) was there and we chatted for ages. The memorial stands on what was the 6000 ft main runway and when you look behind you, you see what is left of it, a small track used for estate business. Other than this and a few inaccessible sections, the remains of the airfield have gone and it is open agriculture once more.

Grafton, like Kimbolton, is split by the road. Leaving the memorial drive back to the village, turn left and follow the road. Along on the left is the former technical site, a few small huts still stand here used by the local farmer. Also, a few feet from the roadside would have been the perimeter track and dispersal pans. What is left of the main entrance, now nothing more than a large blue gate, can be seen as you pass. Odd patches of concrete can also be seen through the thick trees but little else. Then a little further along, passed the equine sign, is another blue gate. Park here. This is the entrance to Grafton Park, a public space, and what was the main thoroughfare to the mess, barracks and squadron quarters. Grafton housed some 3000 personnel of which some 1600 never returned. It is immense! Walking along the path, you can just see the Battle Headquarters, poking out of the trees, the site is very overgrown and nature is claiming back what was once hers. The roads remain and are clearly laid out, some having been recovered with tarmac, but careful observations will see the original concrete beneath. Keep on the ‘Broadway’ and you will pass a number of side roads until you come to the hub. This forms a central octagonal star, off from which were the aptly named: ‘Foxy’ cinema, mess clubs and hospitals. Each road taking you from here, site 3, to the various other sites a short distance away. Careful observations and exploring – there are many hidden ditches and pits – will show foundations and the odd brick wall from the various buildings that remain. A nice touch to the hub, is that it is now a grassed area with picnic tables.

You do lose a sense of this being an airfield; the trees and vegetation have taken over quite virulently and hidden what little evidence remains. Exploring the area, you will find some evidence, but you have to look hard. Walk back along the Broadway, and take the first turn left. Keep an open to the right, and you will see other small buildings, the officers’ quarters and shelters – this was site 4. Again, very careful footing will allow some exploration, but there is little to gain from this.

Considering the size of Grafton Underwood, and then fact that 3000 men and women lived here, there is little to see for the casual eye. A beautiful place to walk, Grafton’s secrets are well hidden; perhaps too well hidden, but maybe the fact that it is so peaceful is as a result and great service to those that fought in that terrible battle above the skies of Europe directly from here.

There is a superb website dedicated to the crews of Grafton Underwood and it can be found at: http://384thbombgroup.com

The memorial has been ‘updated’ since this visit. It was opened on May 22nd 2015 and a video / photos can be seen in the posts below.

1. 7/3/2015, 9/3/15, 11/3/15, 7/5/15 and 9/6/15

During the early 2020s restoration work took place on some of the buildings left on the site. The work can be seen via Facebook.

Leaving Grafton Underwood behind, proceed in a northerly direction. When you pass through Weldon, stop at the church, I believe there is another delightful stained glass window here to commemorate the lives of the crews at this local airfield. But unlike Grafton, the church was sadly locked, so next time I’m down this way I shall stop by.

RAF Deenethorpe (Station 128)

Deenethorpe saw action by 4 squadrons from the 401st Bombardment Group, reputedly “The best damned outfit in the USAAF”. They flew 254 combat missions and received two Distinguished unit Citations. They had the best bombing accuracy of the mighty Eighth and one of the lowest loss ratios of any USAAF unit. However, a local disaster and inauspicious start, did not mean it was all plain sailing.

Deenethorpe October 1942, taken by No. 8 OTU (RAF/FNO/166). English Heritage (RAF Photography). The memorial is to the bottom right (IWM)

Constructed in 1942/43 as a Class ‘A’ airfield, it would have three concrete runways, a main of 2,000 yds and two secondary both 1,400 yds. The main runway ran in a north-east to south-west direction whilst the two secondary runways ran north-west to south-east and east-west respectively. The airfield was built adjacent to the (now) main A427 Weldon to Upper Benefield road and had around 50 loop style hardstands for aircraft dispersal.

For maintenance of the heavy bombers, two ‘T2’ hangars were sited on the airfield, one to the south-eastern corner and the second to the west, next to the apex of the ‘A’. Fuel stores were in the southern and northern sections, away form the technical site located to the south-east. Accommodation sites for 421 Officers and 2,473 enlisted men were also to the south-east beyond the road. Initially used as the RAF as a training base, it was quickly adopted by the USAAF and personnel soon moved in.

The main inhabitants of Deenethorpe were the four squadrons of the 401st BG, 94th Combat Wing, 1st Air Division. This Division, operated from nine airfields, in this Peterborough-Cambridge-Northampton triangle with three further fields to the south-east of Cambridge. A small cluster of sites located close together but away from the main 2nd and 3rd Air Divisions of Norfolk and Suffolk.

The 401st were a short-term unit operating until the end of the war; although they did go on to serve post war in the 1950s following reactivation. Originally constituted on March 20th 1943, they moved through various training airfields eventually arriving in England in October/November 1943.

B-17 Flying Fortress SC-O (42-97487) “Hangover Haven” of the 612th BS/401st BG after crash landing at Deenethorpe, 3rd October 1944 (IWM)

The four squadrons of the 401st, the 612th, 613th, 614th and 615th, all flew B-17Gs and operated with the codes ‘SC’, ‘IN’, ‘IW’ and ‘IY’ respectively. Using a tail code of a white ‘S’ in a black triangle, a yellow band was later added across the fin (prior to September 1943, the tail fin codes were reversed, i.e. black ‘S’ in a white triangle as in the above photo). The ground forces arrived via Greenock sailing on the Queen Mary, whilst the air echelon flew the northern routes via Iceland. Their introduction into the war would be a swift one.

The primary role of the 401st would be to attack strategic targets, such as submarine pens, ship building sites, heavy industrial units, marshalling yards and other vital transport routes. Many of these were heavily defended either by flak or by fighter cover, much of which was very accurate and determined.

On the 26th November 1943 they would fly their first mission – Bremen, headed by their commanding officer Colonel Harold W. Bowman. It was not to be an auspicious start though. With 24 crews briefed, engines started at 08:00, twenty-four B-17s rolled along the perimeter track to their take off positions at the head of the northern end of the main runway.

It was then that B-17 “Penny’s Thunderhead” 42-31098, of the 614th BS, slipped of the perimeter track trapping the following aircraft, commanded by the Station Commander Major Seawell, behind it. Then a further incident occurred where aircraft 42-39873, “Stormy Weather” suffered brake failure and collided into the tail of 42-31091 “Maggie“, severely damaging the tail. Four crews were out of action before the first mission had even started. Bad luck was not to stop there. Once over the target, cloud obscured vision and whilst on the bomb run “Fancy Nancy“, 42-37838, collided with another B17 from the 388thBG. “Fancy Nancy” was luckily able to return to England, but severely damaged it could only make RAF Detling in Kent where it crash landed. So severe was the damage, that it could only be salvaged for parts and scrap. The mission report for the day shows that the ball turret gunner lost his life in the incident, the turret being cut free from the fuselage. A further gunner was wounded by flak and a third suffered frost injuries to his face.

On their second mission, the 401st were able to claim their first kill. A FW-190 was hit over the target at Solingen and the aircraft destroyed, but their luck was not necessarily about to change.

Within a matter of weeks the 401st were to have yet another set back and it was only due to the quick thinking of the crew that casualties were kept to a minimum. On December 5th 1943, mission 3 for the 401st, target Paris; B-17 42-39825, “Zenobia” crashed on take off coming to rest in nearby Deenethorpe village. The uninjured crew vacated the burning aircraft and warned the villagers of an impending explosion. Fire crews and colleagues rushed to the scene, and the two remaining injured crewmen were safely pulled out. Twenty minutes after the initial crash, the aircraft, full of fuel and bombs, finally exploded destroying a number of properties along with the fire tender. The explosion was so enormous, it was heard nine miles away.

The new year however, brought new luck. During operations in both January and February 1944 against aircraft production facilities, the 401st were awarded two DUCs for their action and as part of the 1st Air Division, they would be awarded a Presidential Citation. The 401st attacked many prestige targets during their time at Deenethorpe including: Schweinfurt, Brunswick, Berlin, Frankfurt, Merseburg and Cologne, achieving an incredible 30 consecutive missions without the loss of a single crew member.

Like many of their counterparts, they would go on to support the Normandy invasion, the break out at St Lo. the Siege of Brest and the airborne assault in Holland. They attacked communication lines in the Battle of the Bulge and went on to support the Allied crossing into Hitler’s homeland over the Rhine.

The 401st performed many operations, 254 in total. Their last being on April 20th 1945 to the Marshalling yards at Brandenburg. During the mission, B17 “Der Grossarschvogel” (The Big Ass Bird) was shot down. Five crew members were killed in the crash and several others, who had managed to escape, were beaten by civilians almost killing two of them. Ironically, they were ‘saved’ by Luftwaffe personnel, and in one case, even freed although the orders had been to shoot him.

These were not to be the last 401st fatalities though. On May 5th 1945, VE day of all days, Sgt G. Kinney was hit by the spinning propeller of a taxying B17 killing him; a devastating end to operational activities at Deenethorpe.

On June 20th, the 401st vacated Deenethorpe, returning via the same route they came and were disbanded in the US. Deenethorpe was returned to RAF ownership and retained until the 1960s when it was sold off. The standard design 12779/41 tower was demolished in 1996 and the remainder of site returned to agriculture. All major buildings have been removed as have two of the three runways. The main one still exists today for light aircraft and microlights, as does most of the perimeter track – but as a mere fraction of its former self.

Whilst there is little to see of this once enormous airfield, best views can be obtained from the main road the A427 Weldon to Upper Benefield road. A few miles along from Weldon on your left is the airfield. Stop at the memorial. The original control tower, now gone, stood proud, visible from here beyond the memorial. The technical site would be to your right, and you would be looking almost straight down the secondary runway to your left. The communal and accommodation sites were directly behind you and traces of these can be seen but only as building footings. In the distance you can see the modern-day hangars used to store the microlights,

Access to this area is restricted, prior permission being needed before entering the site, records show that there have been a number of ‘incidents’ with landowners and users of the airfield. So what little remains is best viewed from here.

The memorial is flanked by two flags, is neat and well cared for. The runway layout is depicted on the memorial stone and it proudly states the achievements of the 401st. I am led to believe the ‘Wheatsheaf’ pub further along was the haunt of many an American airman and has a ‘401 bar’ with photos and memorabilia. I was not able to visit this unfortunately and cannot therefore verify this. Definitely one for another day!

Deenethorpe is one of those airfields that has quietly slipped away, the passage of time leaving only simple scars on the landscape. This once busy and prestigious airfield now nothing more than rubble and fields with a memorial to mark the brave actions, the death and the sacrifice made by crews of the United States Army Air Force so long ago.

A BBC news report covered the planting of a time capsule in June 2011, when the widow of Tom Parker (the last of the 401st Bombardment Squadron crew, that flew the B-17 plane “Lady Luck” out of Deenethorpe), kept their promise that whoever was last would bring a collection of tankards back to Deenethorpe with their own personal stories. The tankards were a gift from the pilot of Lady Luck, Lt Bob Kamper who presented them to the crew at a reunion in 1972. Mr Parker, the last member of the crew, sadly died in March 2011.

May their stories live on forever more.

For further accounts of life at Deenethorpe, read the recollections of a B-17 co-pilot through his memories at ‘A Box of Old Letters‘.

The BBC news report can be found here.

Deenethorpe falls under Northampton County Council, and like Kings Cliffe in the same area, has been the subject of planning applications. It is proposed that the airfield be removed and all flying activity stopped. A Garden Village will be built on the site, and the area landscaped accordingly. The proposal can be found here.

From here we go onto an airfield that saw action involving a large numbers of paratroopers, and into the jaws of death – we go to Spanhoe.

RAF Spanhoe (Station 493)

With the BEF evacuation at Dunkirk, some thought that the war was over and that the mighty Nazi war machine was undefeatable. Poised on the edge France, a mere 20 or so miles from the English coast, the armies of the Wehrmacht were waiting ready to pounce and invade England. For Britain though, the defences came up and the determination to defeat this evil regime grew even stronger.

Defeat in the air during the Battle of Britain reversed the fortunes of Germany. Then the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour in the Pacific, which led to the United States joining the war, set the scene for a new and vigorous joint front that would lead to the eventual invasion of occupied Europe, and ultimately the freedom for those held in the grip of the Nazi tyranny.

Plans for the invasion were never far from the thoughts of those in power – even in the darkest hours of both Dunkirk and the Battle for the British homeland. To complete this enormous task, an operation of unprecedented size and complexity would be needed. Vehicles, troops and supplies would all needed to be ferried across the English Channel, a massive air armada would have to fly thousands of young men to the continent. To succeed in this auspicious and daring operation, a number of both training and operational airfields would need to be built, and in 1943 Spanhoe was born.

Known originally as RAF Wakerley (and also referred to as Harringworth or Spanhoe Lodge) it was handed over to the U.S.A.A.F. and designated Station 493.

Located in the county of Northamptonshire, it would be a huge site with three concrete runways, the longest of which was 6000 ft. Two smaller intersecting runways were of 4,200 ft and all three were a huge 150 ft wide. A total of 50 spectacle hardstands were spread around the perimeter track whilst the tower, built to a 1941 design (12779/41), was located to the south of the airfield between the technical area and main airfield. Such was the design of the airfield, that the tower was located a good distance away from the main runway to the north. The technical area included a small number of Quonset huts, temporary brick-built buildings and two T2 hangars. Instructional and training buildings included a Synthetic Navigation Classroom (2075/43) designed with the most up-to-date projection and synthetic training instruments possible. These buildings were made more distinct by the two glazed astrodomes located at one end of the building which could be used on nights when stars were visible.

As Spanhoe was originally built as a bomber station, a bomb and pyrotechnic store was built on the eastern side of the airfield with three huge fuel stores, one to the north and two others to the west, all capable of holding 72,000 gallons of aviation fuel each.

Accommodation for the crews and ground staff was widely spread to the south amongst the local woods and fields, and consisted of numerous cold Quonset huts – but for the residents, Spanhoe was considered nothing special to write home about.

The first U.S. units to arrive were the Troop Carriers the of the 315th Troop Carrier Group (TCG), whose journey from the United States was not as straightforward as most.

Whilst on their way over the north Atlantic route, they were hit by bad weather and had to be diverted to Greenland. Here they stayed for over a month scouring the seas for downed aircraft and dropping supplies to the crews before they were rescued.

Eventually the 315th made England and began a series of training operations. A small detachment were sent to Algiers to assist in the dropping of supplies to troops in the Sicily and Italy campaigns before returning to the main squadron in the U.K. The 315th arrived at Spanhoe on 7th February 1944 now part of the Ninth Air Force, IX Troop Carrier Command, 52nd Troop Carrier Wing. They operated two versions of the adapted Douglas DC-3; the C-47 Skytrain and the C-53 Skytrooper transport aircraft. Four Troop Carrier Squadrons (TCS) would use Spanhoe: the 34th, 43rd, 309th and 310th, and would all operate purely as paratroop carriers.

C-47 Skytrains of the 315th Troop Carrier Group in flight. over the Harringworth Viaduct. RAF Spanhoe, the home of the two Aircraft is just out of shot. (IWM – FRE 3396)

For the next few months they would train in preparation for the forthcoming D-day landings in which they would rehearse both formation flying at night and night paratroop drops with the 82nd Airborne; the unit the 315th would take to drop zones behind enemy lines in Normandy. These preparations were relentless, and not without casualties. The 315th were considered as one of the ‘weaker’ elements of the air invasion force, and would carry out drops nightly until the paratroops had completed their full quota of jumps and all were finally classed as ‘proficient’. The majority of these jumps were however, carried out in clear weather, a point that had not been factored into the final decision.

Flying at night would, unsurprisingly, claim lives and this was brought home when on the night of May 11th-12th, two aircraft from the 315th’s sister group the 316th, collided during combined operations, killing fourteen airmen.

Even with all this training and a very high aircraft maintenance programme, there were many factors that could affect the outcome of operations. Some 40% of crews had only recently arrived before operations, and thus were not a party to a large part of the training missions. Of the 924 crews that were designated for the operations, 20% had only had minimal training and 75% had never actually been under fire. The airborne crews were not well prepared.

On the third day of June the order came through to paint invasion stripes on the aircraft. These three white and two black stripes, each two feet wide, were designed to enable the recognition of allied aircraft who were sworn to radio silence over the invasion zones. D-Day was now imminent.

The 52nd’s mission would involve all the other groups of the Wing, taking aircraft from: Barkston Heath (61st TCG), Folkingham (313th TCG) Saltby (314th TCG) and Cottesmore (316th TCG) as well as eleven other paratroop and glider-towing units of the U.S. Ninth Air Force and fifteen RAF Squadrons – it was going to be an incredible sight.

Forty-eight aircraft took off from Spanhoe and formed up with the other Groups at checkpoint ‘ATLANTA’, they continued on toward Bristol turning south at checkpoint ‘CLEVELAND’ . They flew crossed the south coast at Portland and headed out toward Guernsey. The route would then take them north of the island where the 52nd would turn east and head over the Cherbourg Peninsula. They would drop their load of heavily laden paratroops south of Utah beach to capture the important town of St. Mere-Eglise. A ten-mile wide corridor would be filled with aircraft and gliders.

Over the drop zone the aircraft encountered cloud and heavy flak. Whilst a quarter received damage, all but one were able to return to England, the last being lost over the drop zone. For their efforts that night, the 315th TCG was awarded the Distinguished Unit Citation, the only one they would receive during the war.

After D-day, units of the 315th continued to drop supplies to the advancing troops, a default role they carried out for much of the war.

Tragedy was to rear its ugly head again and strike down Spanhoe crews. In July 1944, 369 Polish paratroopers arrived for training as part of Operation ‘Burden’. This involved thirty-three C-47s of the 309th TCS, fully loaded flying in formation at around 1,300 ft. The aim of the flight was to drop the Polish Paratroops at a drop zone (DZ) over R.A.F. Wittering.

Shortly before arriving at the DZ near to the Village of Tinwell, two aircraft made deadly contact and both plummeted to the ground. Twenty-six paratroops and eight crewmen were killed that day, the only survivor was Corporal Thomas Chambers who jumped from an open door. Eyewitness accounts tell of “soil soaked in aviation fuel”, and bodies strapped to part open parachutes as many tried to jump as the aircraft fell. This tragic accident was a devastating blow to the Polish troops especially as they had not yet been able to prove themselves in combat and one that ultimately led to the disbandment of the section and reabsorption into other units.*1

The 315th’s next major combat mission would be ‘Market Garden‘ on September 17th, 1944, another event that led to many tragedies. On the initial day, ninety aircraft left Spanhoe with 354 Paratroops of the U.S. 82nd Airborne, the following day another fifty-four aircraft took British paratroops and then on the third day they were to take Polish troops. However, bad weather continually caused the cancellation of the Polish operations and even with attempts at take-offs, it wasn’t to be. Finally on September 23rd good skies returned and operations could once more be carried out. During all this time, the Polish troops were loaded and unloaded, stores under the wings of the C-47s were added and then removed, it became so frustrating that one Polish paratrooper, unable to cope with the stress and anticipation of operations, fatally shot himself.

Later that month, another plan was hatched to resupply the beleaguered troops in Holland. The idea was to land large numbers of C-47s on different airfields close to Nijmegen. Not sure if they had been secured, or even taken, the daring mission went ahead. Escorting fighters and ground attack aircraft neutralised anti-aircraft positions around the airfields allowing hundreds of C-47s to land, deposit their supplies and take off again, in a mission that took over six hours to complete. In total: jeeps, trailers, motorcycles, fuel, ammunition, rations and 882 new troops were all delivered safely without the loss of a single transport aircraft – a remarkable feat.

Further supplies were dropped to troops during both the Battle of the Bulge and Operation Varsity – the crossing of the Rhine – in March 1945. During this operation, the 315th would drop more British paratroopers near Wesel, Germany, a mission that would cost 19 aircraft with a further 36 badly damaged.

By now the Allies were in Germany and the Troop Carrier units were able to move to France leaving their U.K. bases behind. This departure signalled the operational end for Spanhoe and all military flying at the airfield would now cease.

Two months later the 253rd Maintenance Unit arrived and prepared Spanhoe for the receiving of thousands of military vehicles that would soon be arriving from the continent. Now surplus to requirements, they would either be scrapped or sold off, Spanhoe became a huge car park and at its height, would accommodate 17,500 vehicles. For the next two years trucks, trailers and jeeps of all shapes and sizes would pass through, until in 1947 the unit left and the site was closed for good and eventually sold off.

This was not the end for Spanhoe though. Aviation and controversy would return again for a fleeting moment on August 12th 1960, with the crash of Vickers Valiant BK1 ‘XD864’ of 7 Squadron RAF. The aircraft, piloted by Flt. Lt. Brian Wickham, took off from its base at nearby RAF Wittering, turned and crashed on Spanhoe airfield just three minutes after take off. The official board of enquiry concluded that the accident was caused by pilot error and that Flt. Lt. Wickham, was guilty of “blameworthy negligence”. The Boards findings were investigated by an independent body who successfully identified major flaws in both the analysis and the Boards subsequent findings. Sadly no review of the accident or the Boards decision has ever taken place since.

Spanhoe was the home of the 315th Troop Carrier Group, part of the 52nd Troop Carrier Wing, Ninth Air Force.

Spanhoe was then turned into a limestone quarry by new owners, the runways and the majority of the perimeter track was dug up and the substrate was removed. The majority of the buildings were demolished but a few were left and now survive as small industrial units involved in, amongst other things, aircraft maintenance and preservation work. A private flying club has also started up and small light aircraft now use what remains of the southern section of the perimeter track and technical area.

The main entrance to the airfield is no longer grand, and in no way reflects the events that once took place here. From this point you can see some of the original technical buildings and hidden behind the thicket, what was possibly a picket post. A footpath though the nearby woods allows access to the remains of eastern end of the main runway and perimeter track, other than this little is accessible without permission.

Outside the main entrance are two memorials consisting of a modern board detailing the group and squadron codes, and a stone obelisk listing the names of those crew members who failed to come home. Both are well cared for if not a little weathered.

Spanhoe leaves a legacy, for both good reasons and bad. The crews that left here taking hundreds of young men into the jaws of death showed great bravery and skill. Determination to be the best and perform at the limits were driving factors behind their successes. Relentless training led to the deaths of many who had never even seen combat, and the scars of these events linger in what remains of the airfield today. Thankfully for the time being, the spirit of aviation lives on, and Spanhoe clings to the edge, each last gasp of breath a reminder of those brave men who flew defenceless in those daring and dangerous missions over occupied Europe.

On leaving Spanhoe, return to the main road, keeping the airfield to your left, join the A43, and then turn right and then immediately left. Follow signs to Oundle and Kings Cliffe and our next destination, the former airfield at Kings Cliffe, an airfield with its own modern controversies.

RAF Kings Cliffe (Station 367)

Unlike the other airfields in the tour, Kings Cliffe was a fighter airfield. Pass through the village from the south, out the other side, under the odd twin-arched bridge and then right. A few hundred yards along and the airfield is now on your right hand side. The memorial is here, flanked by the two flags. It is a more elaborate memorial than some, being made with the wing of a Spitfire on one side and the wing of a Mustang on the other. Various squadron badges are etched into the stone and as the weather takes it’s toll, these are gradually disappearing.

Over its life, Kings Cliffe would have a number of fighter units grace it skies. Built in 1943, it would receive its first squadron late that same year when P-39 Airacobras of Duxford’s 347th FS (350th FG) were temporarily based here. A short spell they would soon leave and be replaced with another short-term unit.

Protected aircraft pen, with ‘dual skin’ defences on three sides. A number of these litter the site.

The following January, the 347th left and three squadrons: the 61st (code HV), 62nd (code LM) and the 63rd (code UN) of the 56th FG arrived from the U.S. This group fell under the command of the 67th Fighter Wing, Eighth Air Force. Re-designated the 56th FG in the previous May, they were initially given P-47s and continued to train at Kings Cliffe for fighter operations until moving on the 4th/6th April 1943 to Horsham St Faith, Norfolk. A few days later on 13th April 1943, they undertook their first operational sortie. Over the next two years the 56th FG would become famous for the highest number of destroyed aircraft of any fighter unit of the entire Eighth Air force. A remarkable feat.

After the 56th left Kings Cliffe, three more squadrons arrived. In August that year, the 20th FG arrived with their P-38 Lightnings. The 55th (code KI), 77th (code LC) and the 79th (code MC), would fall under the umbrella of the 67th Fighter Wing, Eighth Airforce.

After a spell of renaming, aircraft changes and training, their arrival at Kings Cliffe would see a period of stability for the 20th. Initial operations started in December that year, and their primary role would be to escort bombers over Europe, a role it maintained until the cessation of conflict. Targets of opportunity were often found whilst on these missions, but toward the end of the war, with fighter cover becoming less of an issue, dive bombing and ground attack missions became more common place. Their black and white chequered markings became feared by airfields, barracks and in particular trains as they became known as the “Loco Group” for their high number of locomotive attacks.

On April 8th 1944, the 20th attacked an airfield in Germany, action for which they received a Distinguished Unit Citation (DUC). They would later take part in the Normandy invasion, Operation Market Garden, and air cover in the Battle of Bulge. In July 1944 they converted to P-51s and continued to escort bombers and search out targets of opportunity until the war closed. In the following October 1945, they returned to the U.S. and Kings Cliffe was returned to RAF ownership. The RAF would use it as a storage depot until selling it off in 1959. Its runways were dug up for hardcore, the buildings demolished and the site finally returned to agriculture.

Whilst standing at the memorial, it is difficult to imagine any of the activity that occurred here all those years ago. However, behind the memorial you can see a number of brick defence buildings enshrouded in trees and bushes. Move along the road to your right and there is the main gate. Stating that it is an airfield, it doesn’t encourage entrance. However, walk or drive a little further and there is a bridal way that allows access to the site. Walking along around the edge of the airfield, you can see hidden amongst the thorn bushes an Oakington Pill box. Found in pairs and common in this area, they offer a 360 degree view of the site. The second of the pair is short distance away in the middle of the field and more visible to the viewer. Also round here are three protected dispersal pens. Each pen has a double skin, in other words, an outside loop holed wall for firing through and an inner wall to protect air and ground crews in the event of an attack. There are a handful of other ancillary buildings here, all of which can be accessed with careful treading. A considerable number of these exist close to the road and path, so extensive travelling or trespass is not required for the more ‘informal’ investigation.

Walking further along the path, you pass a large clump of trees heading of in an easterly direction. These mark the line of the east-west runway. Whilst the runway has gone, evidence of its existence can be found. A drainage channel, numerous pieces of drainage material and grates can be found amongst the remains of hardcore.

The path continues in a southerly direction away from the main part of the airfield, and a better option may be to return to the car and drive along to a different part of the site.

If you return through Kings Cliffe, bear left and through the small but gorgeous village of Apethorpe. Continue on and you’ll see a footpath that goes through the woods. Park here and walk through the woods. A couple of miles in and you come across a large open space, to your left is a distinguished memorial to Glenn Miller.

The memorial is located on the site of the original T2 hangar, quite a distance away from the main airfield. It was here that Miller performed his final hangar concert on October 3rd 1944. Standing here in the wintry air listening to ‘In the Mood’, is a surreal experience. To think that, on this spot 70 years ago, this very tune was performed by Miller himself; whilst young couples jitterbugged the evening away – a brief respite from the wartime tragedies that dominated their daily lives.

Leaving here, back to the track, you come across a footpath that takes you north, toward the main airfield before veering off and away to the west.

This path provides what is probably the nearest access point to the tower, as it crosses the track that joins the perimeter near to the towers location. The control tower still stands, but access from the path is over private land and should be undertaken with the land owner’s permission.

A final car trip back to the north side of the airfield reveals evidence of the accommodation blocks. The cinema, Gymnasium and chapel along with some other communal buildings still stand and in use by local timber companies. Well preserved, they are easily accessible and offer a good view to anyone aiming to find evidence of Kings Cliff’s history.