After visiting the many museums and former airfields in the southern and central parts of Kent (Trail 4 and Trail 18) we now turn north and head to the northern coastline. Here we overlook the entrance to the Thames estuary, the Maunsell Forts – designed to protect the approaches to London and the east coast – and then take a short trip along the coastline of northern Kent. Our first stop is not an airfield nor a museum, it is a statue of the designer of one of the world’s most incredible weapons – the bouncing bomb. Our first short stop is at Herne Bay, and the statue of Sir Barnes Wallis.

Sir Barnes Wallis – Herne Bay

There cannot be a person alive who has not seen, or knows about, the famous Dambusters raid made by 617 Sqn. It is a story deeply embedded in history, one of the most daring raids ever made using incredible ideas, skill and tenacity. There is so much written about both it, and the man behind the idea – Sir Barnes Neville Wallis CBE FRS RDI FRAeS.

Wallis was a man famous for his engineering prowess and in particular the famous ‘Bouncing Bomb’ that was used by Guy Gibson’s 617 Squadron in that daring raid of 16th May 1943. But there is so much more to Barnes Wallis than the Bouncing bombs; he made a huge contribution to British Aviation, weaponry of the Second World War, and later on in his life, supersonic and hypersonic air travel. He is certainly one the Britain’s more notable designers, and has memorials, statues and plaques spread across the length and breadth of the country in his honour.

But he was not just a designer of the Bouncing bomb, his talent for engineering and design led him through a series of moves that enabled him to excel and become a major part of British history.

Born on 26th September 1887 in Ripley, Derbyshire, he was educated at Christ’s Hospital in Horsham, he went on to study engineering in London, and shortly afterwards moving to the Isle of Wight. With the First World War looming, he was offered a chance to work on airship designs – an innovative design that would become widely used by the Naval forces of both the U.K. and Germany. Wallis cut his teeth in marine engines as an engineer and draughtsman.

He began his career in the London’s shipyards, moving to the Isle of Wight after which he broke into airship design. He followed a colleague he had met whilst working as a draughtsman with John Samuel White’s shipyard, together they would design His Majesty’s Airship No.9 (HMA 9). The design process of HMA 9 was dynamic to say the least. Early non-rigid airships were proving to be very successful, and the new rigids that were coming in – whilst larger and more capable of travelling longer distances with greater payloads – were becoming the target for successive quarrels between the government and the Admiralty.

World unrest and political turmoil was delaying their development even though plans for HMA 9 had already been drawn up. Joining with his colleague, H.B. Pratt in April 1913, at the engineering company Vickers, the two designers began drawing up plans for a new rigid based along the lines of the German Zeppelin. HMA 9 would be a step forward from the ill-fated HMA No. 1 “Mayfly”, and would take several years to complete. Further ‘interference’ from the Admiralty (One Winston Churchill) led to the order being cancelled but then reinstated during 1915. The final construction of the 526 ft. long airship was on 28th June 1916, but its first flight didn’t take place until the following November, when it became the first British rigid airship to take to the Skies.

With this Wallis had made his mark, and whilst HMA 9 remained classed as an ‘experimental’ airship with only 198 hours and 16 minutes of air time, she was a major step forward in British airship design and technology.

The Pratt and Wallis partnership were to go on and create another design, improving on the rigids that have previously been based on Zeppelin designs, in the form of the R80. Created through the pressure of war, the R80 would have to be designed and built inside readily available sheds as both steel and labour were in very short supply. Even before design or construction could begin there were barriers facing the duo.

Construction started in 1917, but with the end of the war in 1918, there was little future as a military airship for R80. Dithering by the Air Ministry led to the initial cancellation of the project, forcing the work to carry on along a commercial basis until the project was reinstated once more. With this reinstatement, military modifications, such as gun positions, were added to the airship once again.

With construction completed in 1920, she made her first flight that summer. However, after sustaining structural damage she was returned to the sheds where repair work was carried out, and a year later R80 took to the air once again. After a brief spell of use by the U.S. Navy for training purposes, R80 was taken to Pulham airship base in Norfolk and eventually scrapped.

Wallis’s design had lasted for four years and had only flown for 73 hours. However, undaunted by these setbacks, the Vickers partnership of Pratt and Wallis went on to develop further designs. In the 1920s, a project known as the 1924 Imperial Airship Scheme, was set up where by a Government sponsored developer would compete against a commercial developer, and the ‘best of both’ would be used to create a new innovative design of airship that would traverse the globe. This new design, would offer both passenger and mail deliveries faster than any current methods at that time.

The Government backed design (built at the Royal Airship Works at Cardington) would compete against Vickers with Wallis as the now Chief Designer. The brief was for a craft that could transport 100 passengers at a speed of 70 knots over a range of 3,000 miles. Whilst both designs were similar in size and overall shape, they could not have been more different. Wallis, designing the R.100, used a mathematical geodetic wire mesh which gave a greater gas volume than the Government’s R101, which was primarily of stainless steel and a more classic design. This geodesic design was revolutionary, strong and lightweight, it would prove a great success and emerge again in Wallis’s future.

Built at the Howden site a few miles west of Hull, the R100 was designed with as few parts as possible to cut down on both costs and weight; indeed R100 had only 13 longitudinal girders half that of previous designs. Wallis’s design was so far-reaching it only used around 50 different main parts.

The design plan of Wallis’ R-100 airship*2

The 1920s in Britain were very difficult years, with the economy facing depression and deflation, strikes were common place, and the R100 was not immune to them. Continued strikes by the workers at the site repeatedly held back construction, but eventually, on 16th December 1929, Wallis’s R100 made its maiden flight. After further trials and slight modifications to its tail, the R100 was ready.

Then came a test of endurance for the airship, a flight to Canada, a flight that saw the R100 cover a journey of 3,364 miles in just under 79 hours. Welcomed as heroes, the return journey would be even quicker. Boosted by the prevailing Gulf Stream, R100 made a crossing of 2,995 miles in four minutes under 58 hours. The gauntlet had been thrown, and Wallis’s airship would be hard to beat.

The R101 would face a similar flight of endurance, this time to India, and it would use many of the same crew such was the shortage of experienced men. On October 4th 1930, R101 left its mooring at Cardington for India. Whilst over France she encountered terrible weather, a violent storm caused her to crash, whereupon she burst into flames and was destroyed with all but six of the 54 passengers and crew being killed. The airship competition became a ‘one horse race’, but an inspection of the outer covering of Wallis’s R100 revealed excessive wear, only cured by replacing the skin, an expense the project could barely swallow.

With plans already in place for the R102, the project was in jeopardy, and eventually, even after offers from the U.S. Government, it was deemed too expensive, and by 1932 R100, the worlds largest airship and most advanced of its time, had been scrapped and the parts sold off. Wallis’s airship career had now come to an end, but his prowess and innovation as a designer had been proven, he had set the bench mark that others would find hard to follow.

With the outbreak of the Second World War, new designs of aircraft and weapons were much-needed. Wallis’s geodesic design, as used in the R100, had been noticed by another Vickers designer Rex Pierson, who arranged for Wallis to transfer to Weybridge, where they formed a new team – Pierson working on the general design of the aircraft with Wallis designing the internal structures. This was a team that produced a number of notable designs including both the Wellesley and the Wellington; both of which utilised Wallis’s geodetic design in both the fuselage and wing construction. What made Wallis’s idea so revolutionary was that the design made the air frame both light-weight and strong, and by having the bearers as part of the skin, it left more room inside the structure thus allowing for more fuel or ‘cargo’. An idea that helped provide greater gas storage for the R100.

Whilst both the Wellesley and the Wellington went on to be successful in the early stages of the war (11,400 Wellingtons saw service), they were both withdrawn from front line service by the mid war years, being replaced by more modern and advanced aircraft that could fly further and carry much larger payloads. Saddened by the rising death toll, Wallis put many of his efforts into shortening the war. His idea was that if you attack and destroy the heart of production, then your enemy would have nothing to fight with; in this case, its power supply.

To this end he started investigating the idea of breaching the dams of the Ruhr. Wallis’s idea was to place an explosive device against the wall of the dam, thus utilising the water’s own pressure to fracture and break open the dam. Conventional bombing was not suitable as it was too difficult to place a large bomb accurately and sufficiently close enough to the dam to cause any significant damage. His idea, he said, was “childishly simple”. Using the idea that spherical objects bounce across water, like stones thrown from a beach, he determined that a bomb could be skimmed across the reservoir over torpedo nets and strike the dam. A backward spin, induced by a motor in the aircraft’s fuselage, would force the bomb to keep to the dam wall where a detonator would explode the bomb at a predetermined depth, similar in fashion to a naval depth charge. The idea was simple in practical terms, ‘skip shot‘ being used with great success by sailors in Nelson’s navy; but it was going to be a long haul, to not only build such a weapon, the aircraft to drop it, nor train the expert crews to fly the aircraft; but to simply convince the Ministry of Aircraft Production that it was in fact feasible.

Wallis began performing a number of tests, first at his home using marbles and baths, then at Chesil Beach in Dorset. Both the Navy and the Ministry were interested when shown a film of the bomb in action, each wanting it for their own specific target; the Navy for the Tirpitz, and the Ministry for the dams. Wallis still determined to use it on the dams, carried out two projects side-by-side, “Upkeep” for the dams, and “Highball” for the Navy*3. “Upkeep” was initially spherical, and the first drop from a modified Lancaster took place in April 1943 at Reculver near to Herne Bay, where this statue is located. He persevered with aircraft heights, speeds and bomb design modifications, carefully honing them until on April 29th 1943, only three weeks before the actual attack, the bomb finally worked for the first time. Wallis’s plan could now be put into action, and with a new squadron of the RAF’s elite bomber crews put in place, the stage was set and the dams of Ruhr Valley would be the target.

The attack on the dams have become legendary, and of the 19 aircraft of 617 Squadron that took off that May evening in 1943, only 11 returned, some after sustaining considerable damage. Operation Chastise saw two of the three dams, the Mohne and Eder, successfully breached and the third, the Sorpe, severely damaged forcing the Germans to partially drain it for safety.

The names of the crews of 617 Squadron at RAF Scampton. Those with poppies next to them, did not return.

Following the success of Operation Chastise, Wallis went on to develop other bombs capable of devastating results. His initial plan, a Ten ton (22,000lb) bomb, had to be scaled back to 12,000lb as there was no aircraft capable of dropping it at that time.

Codenamed ‘Tallboy’, it would be a deep penetration bomb 21 feet in length with a hardened steel case and 4 inches of steel in the nose. The bomb contained 5200lbs of high explosive Torpex (similar to that used in the Kennedy Aphrodite mission) and would have a terminal velocity of around 750 miles per hour. The idea of Tallboy, was to create a deep underground crater into which structures would either fall or be rendered irreparable. With a time fuse that could be set to sixty minutes after release, it was used on strategic targets such as the Samur Railway Tunnel in France, rendering the tunnel useless as it had to be closed for a considerable amount of time.

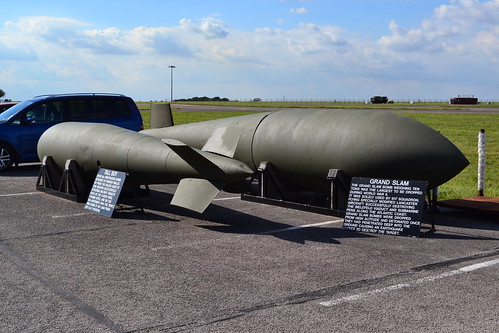

Soon after this, Wallis began developing his Ten Ton bomb, the “Grand Slam“, a mighty 26ft in length, it weighed 22,000lb, and would impact the ground at near supersonic speeds. Wallis’s design was such that the bomb could penetrate through 20 feet of solid concrete or 130 feet of earth, where it would explode creating a mini earthquake. It was this earthquake that would rock the foundations of buildings and structures, or simply suck them into a crater of massive proportions*5. Production of the Grand Slam was slow though. It took two days for the casting to cool and then after machining, it took a further month for the molten Torpex to set and cool. The first use of the Grand Slam occurred on 14th March 1945 against the Bielefeld Viaduct in Germany, on which one Grand Slam and 27 Tallboys were dropped. Unsurprisingly, the viaduct collapsed and the railway was put out of action. Wallis had created more exceptionally devastating weapons, they were so successful that 854 Tallboys and 41 Grand Slams were dropped by the war’s end.

Post war, Wallis carried on with his design and investigations into aerodynamics and flight. He was convinced that achieving supersonic flight with the greatest economy was the way forward, and in particular variable geometry wings. The government was keen to catch up with the U.S., awarding Vickers £500,000 to carry out research into supersonic flight. Wallis’s project received some of this money, and he researched unmanned supersonic flight in the form of surface-to-air missiles. Codenamed ‘Wild Goose‘ (later ‘Green Lizard’) the project ran to 1954 when it was terminated. Wallis continued with his research into swing wing designs, his first being the JC9, a single seat aircraft 46 feet in length. It was produced but never completed and was scrapped before it ever got off the ground. Wallis wasn’t put off though, and he continued on developing the ‘Swallow’, a swing wing aircraft that could reach speeds of Mach 2.5 in model wind tunnel investigations.

In its bomber form it would have been equivalent in size to the American B-1, with a crew of 4 or 5, and a cruising speed of Mach 2. It would have a range of 5,000 miles whilst carrying a single Red Beard nuclear bomb. Whilst not selected to meet the R.A.F.’s OR.330 (Operational Requirement 330), which was eventually awarded to TSR.2, they were interested enough for him to proceed until the 1957 Defence White Paper put an end to the project, and it was cancelled. Looking for funding Wallis turned to the U.S. hoping they would grant him sufficient funds to continue his work.

After many meetings between Wallis and the U.S American Mutual Weapons Development Program at NASA’s Langley research facility, he came away disappointed and saddened that the Americans used his ideas without granting him any funding. American research continued, eventually developing into the successful General Dynamics F-111 ‘Aardvark‘, the world’s first production swing-wing combat aircraft.

Wallis continued with other supersonic and hypersonic investigations; designs were drawn up for an aircraft capable of Mach 4-5, using a series of variable winglets to link subsonic, supersonic and hypersonic flights, many however, never went beyond the drawing board. Wallis didn’t stop there, he continued with many great inspirational projects: the Stratosphere Chamber, a test chamber where by simulated impacts on aircraft travelling at 70,000 feet could be safely tested and analysed; the Parkes Telescope, a radio telescope in New South Wales; the Momentum Bomb, a nuclear bomb designed to be released at low-level and high-speed, enabling the release aircraft to escape the blast safely, and in the 1960s, a High Pressure Submarine designed to dive deeply beyond the range of current detection.

In recognition of his work, Wallis was knighted in 1968, and he was also made an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Aeronautical Society. Wallis, after working beyond his forced retirement, died at the age of 83, on 30th October 1979, in Effingham, Surrey.

He is buried in the local church, St Lawrence’s Church, in Effingham, a village he contributed greatly to. He was the church secretary for eight years, and an Effingham Parish Councillor, serving as Chairman for 10 years. He was also the Chairman of the Local Housing Association, which helped the poor and elderly of the village to find or build homes; and as a fanatical cricketer, he was Chairman of the KGV Management Committee who negotiated the landscaping of the “bowl” cricket ground, so good was the surface, it was used as a substitute for the Oval in London. There are numerous memorials and dedications around the country to Wallis, and there is no doubt that he was both an incredible engineer and inventor who made a major contribution to not only the war, but British and world aviation in general. His statue at Herne Bay overlooks Reculver where the first “Upkeep” bomb was dropped by a Lancaster bomber during the Second World War, and it is a fine tribute to this remarkable man on this trail.

Sir Barnes Neville Wallis (Barnes Wallis Foundation)

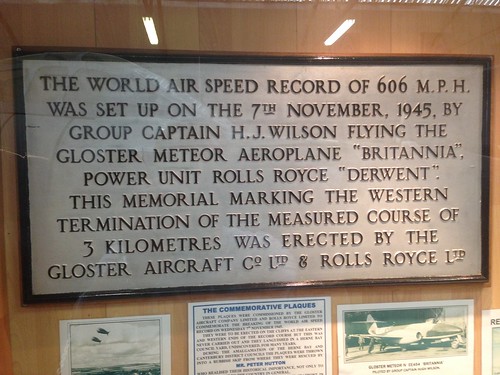

Before leaving Herne Bay, take a look out to sea and imagine yourself watching a Gloster Meteor flash by. On November 7th 1945, this very event occurred during which a new World Air Speed record was set.

The World Air Speed Record.

On that day, two Meteor aircraft were prepared in which two pilots, both flying for different groups, would attempt to set a new World Air Speed record over a set course along Herne Bay’s seafront.

The first aircraft was piloted by Group Captain Hugh Joseph Wilson, CBE, AFC (the Commandant of the Empire Test Pilots’ School, Cranfield); and the second by Mr. Eric Stanley Greenwood O.B.E., Gloster’s own chief test pilot. In a few hours time both men would have the chance to have their names entered in the history books of aviation by breaking through the 600mph air speed barrier.

The event was run in line with the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale‘s rules, covering in total, an 8 mile course flown at, or below, 250 feet. For the attempt, there would be four runs in total by each pilot, two east-to-west and two west-to-east.

With good but not ideal weather, Wilson’s aircraft took off from the former RAF Manston, circling over Thanet before lining his aircraft up for the run in. Following red balloon markers along the shoreline, Wilson flew along the 8 mile course at 250 feet between Reculver Point and Herne Bay Pier toward the Isle of Sheppey.

Above Sheppey, (and below 1,300 ft) Wilson would turn his aircraft and line up for the next run, again at 250ft. Initial results showed Greenwood achieving the higher speeds, and these were eagerly flashed around the world. However, after confirmation from more sophisticated timing equipment, it was later confirmed that the higher speed was in fact achieved by Wilson, whose recorded speeds were: 604mph, 608mph, 602mph and 611mph, giving an average speed of just over 606mph. Eric Greenwood’s flights were also confirmed, but slightly slower at: 599mph, 608mph, 598mph and 607mph, giving an overall average speed of 603mph. The actual confirmed and awarded speed over the four runs was 606.38mph by Wilson*1.

The event was big news around the world, a reporter for ‘The Argus*2‘ – a Melbourne newspaper – described how both pilots used only two-thirds of their permitted power, and how they both wanted permission to push the air speed even higher, but both were denied at the time.

In the following day’s report*3, Greenwood described what it was like flying at over 600 mph for the very first time.

As I shot across the course of three kilometres (one mile seven furlongs), my principal worry was to keep my eye on the light on the pier, for it was the best guiding beacon there was.

On my first run I hit a bump, got a wing down, and my nose slewed off a bit, but I got back on the course. Below the sea appeared to be rushing past like an out-of-focus picture. I could not see the Isle of Sheppey, toward which I was heading, because visibility was not all that I wanted. At 600mph it is a matter of seconds before you are there. It came up just where I expected it.

In the cockpit I was wearing a tropical helmet, grey flannel bags, a white silk shirt, and ordinary shoes. The ride was quite comfortable, and not as bumpy as some practice runs. I did not have time to pay much attention to the gauges and meters, but I could see that my air speed indicator was bobbing round the 600mph mark. On the first run I only glanced at the altimeter on the turns, so that I should not go too high. My right hand was kept pretty busy on the stick (control column), and my left hand was. throbbing on the two throttle levers.

Greenwood went on to describe how it took four attempts to start the upgraded engines, delaying his attempt by an hour…

I had to get in and out of the cockpit four times before the engines finally started. A technical hitch delayed me for about an hour, and all the time I was getting colder and colder. At last I got away round about 11.30am.

He described in some detail the first and second runs…

On the first run I had a fleeting glance at the blurred coast, and saw quite a crowd of onlookers on the cliffs. I remembered that my wife was watching me, and I found that there was time to wonder what she was thinking. I knew that she would be more worried than I was, and it struck me that the sooner I could get the thing over the sooner her fears would be put at rest.

On my first turn toward the Isle of Sheppey I was well lined up for passing over the Eastchurch airfield, where visibility was poor for this high-speed type of flying. The horizon had completely disappeared, and I turned by looking down at the ground and hoping that, on coming out of the bank, I would be pointing at two balloons on the pier 12 miles ahead. They were not visible at first. All this time my air speed indicator had not dropped below 560 mph, in spite of my back-throttling slightly. Then the guiding light flashed from the pier, and in a moment I saw the balloons, so I knew that I was all right for that.

On the return run of my first circuit the cockpit began to get hot. It was for all the world like a tropical-summer day. Perspiration began to collect on my forehead. I did not want it to cloud my eyes, so for the fraction of a second I took my hands off the controls and wiped the sweat off with the back of my gloved hand. I had decided not to wear goggles, as the cockpit was completely sealed. I had taken the precaution, however, of leaving my oxygen turned on, because I thought that it was just that little extra care that might prevent my getting the feeling of “Don’t fence me in.” Normally I don’t suffer from a feeling of being cooked up in an aircraft, but the Meteor’s cockpit was so completely sealed up that I was not certain how I should feel.

As all had gone well, and I had got half-way through the course I checked up my fuel content gauges to be sure that I had plenty of paraffin to complete the job. I passed over Manston airfield on the second run rather farther east than I had hoped, so my turn took me farther out to sea than I had budgeted for. But I managed to line up again quite satisfactorily, and I opened up just as I was approaching Margate pier at a height of 800 feet. My speed was then 560 mph.

Whilst the first run was smooth, the second he said, “Shook the base of his spine”.

This second run was not so smooth, for I hit a few bumps, which shook the base of my spine. Hitting air bumps at 600 mph is like falling down stone steps—a series of nasty jars. But the biffs were not bad enough to make me back-throttle, and I passed over the line without incident, except that I felt extremely hot and clammy.

After he had completed his four attempts, Greenwood described how he had difficulty in lowering his airspeed to enable him to land safely…

At the end of my effort I came to one of the most difficult jobs of the lot. It was to lose speed after having travelled at 600 mph. I started back-throttling immediately after I had finished my final run, but I had to circuit Manston airfield three times before I got my speed down to 200mph.

The two Meteor aircraft were especially modified for the event. Both originally built as MK.III aircraft – ‘EE454’ (Britannia ) and ‘EE455’ (Yellow Peril) – they had the original engines replaced with Derwent Mk.V turbojets (a scaled-down version of the RB.41 Nene) increasing the thrust to a maximum of 4,000 lbs at sea level – for the runs though, this would be limited to 3,600 lbs each. Other modifications included: reducing and strengthening the canopy; lightening the air frames by removal of all weaponry; smoothing of all flying surfaces; sealing of trim tabs, along with shortening and reshaping of the wings – all of which would go toward making the aircraft as streamlined as possible.

EE455 ‘Yellow Peril’ was painted in an all yellow scheme (with silver outer wings) to make itself more visible for recording cameras.*4

An official application for the record was submitted to the International Aeronautical Federation for world recognition. As it was announced, Air-Marshal Sir William Coryton (former commander of 5 Group) said that: “Britain had hoped to go farther, but minor defects had developed in ‘Britannia’. There was no sign of damage to the other machine“, he went on to say.

Wilson, born at Westminster, London, England, 28th May 1908, initially received a short service commission, after which he rose through the ranks of the Royal Air Force eventually being placed on the Reserves Officers list. With the outbreak of war, Flt. Lt. Wilson was recalled and assigned as Commanding Officer to the Aerodynamic Flight, R.A.E. Farnborough. A year after promotion to the rank of Squadron Leader in 1940, he was appointed chief test pilot at the Royal Aircraft Establishment (R.A.E.) who were then testing captured enemy aircraft. He was promoted to Wing Commander, 20th August 1945, retiring on 20th June 1948 as a Group Captain. Eric Greenwood, Gloster’s Chief Test Pilot, was credited with the first pilot to exceed 600 miles per hour in level flight, and was awarded the O.B.E. on 13th June 1946.

His career started straight from school, learning to fly at No. 5 F.T.S. at Sealand in 1928. He was then posted to 3 Sqn. at Upavon flying Hawker Woodcocks and Bristol Bulldogs before taking an instructors course, a role he continued in until the end of his commission.

After leaving the R.A.F., Greenwood joined up with Lord Malcolm Douglas Hamilton (later Group Captain), performing barnstorming flying and private charter flights in Scotland. Greenwood then flew to the far East to help set up the Malayan Air Force under the guise of the Penang Flying Club. His time here was adventurous, flying some 2,000 hours in adapted Tiger Moths. His eventual return to England saw him flying for the Armstrong Whitworth, Hawker and Gloster companies, before being sent as chief test pilot to the Air Service Training (A.S.T.) at Hamble in 1941.

Here he would test modified U.S. built aircraft such as the Airocobra, until the summer of 1944 when he moved back to Gloster’s – again as test pilot. It was whilst here at Gloster’s that Greenwood would break two world air speed records, both within two weeks of each other. Pushing a Meteor passed both the 500mph and 600mph barriers meant that the R.A.F. had a fighter that could not only match many of its counterparts but one that had taken aviation to new record speeds.

During the trials for the Meteor, Greenwood and Wilson were joined by Captain Eric ‘Winkle’ Brown, who between them tested the slimmed-down and ‘lacquered until it shone’ machine, comparing drag coefficients with standard machines. Every inch of power had to be squeezed from the engine as reheats were still in their infancy and much too dangerous to use in such trials.

To mark this historic event, two plaques were made, but never, it would seem, displayed. Reputed to have been saved from a council skip, they were initially thought to have been placed in a local cafe, after the cliffs – where they were meant to be displayed – collapsed. The plaques were however left in the council’s possession, until saved by an eagle-eyed employee. Today, they are located in the RAF Manston History Museum where they remain on public display.

To mark the place in Herne Bay where this historic event took place, an information board has been added, going some small way to paying tribute to the men and machines who set the world alight with a new World Air Speed record only a few hundred feet from where it stands.

Part of the Herne Bay Tribute to the World Air Speed Record set by Group Captain H.J. Wilson (note the incorrect speed given).

For a ‘small’ seaside town Herne Bay has strong aviation links. In addition to both Barnes Wallis and 617 Sqn, and the World Air Speed record, it was also the site where that famous female aviatrix Amy Johnson, mysteriously and so tragically disappeared.

Amy Johnson – aviatrix

Amy Johnson is one of those names known the world over for her achievements in aviation, being the first woman to fly solo halfway around the world from England to Australia in 1930. This amongst numerous other flying achievements made her one of the most influential women of the 1900s. She was born in 1903, at 154 St. George’s Road in Kingston upon Hull, in the East Riding of Yorkshire.

The eldest daughter of John William Johnson and Amy Hodge, she was the oldest of four sisters. Her education took her through Boulevard Municipal Secondary School and on to the University in Sheffield, where she studied economics at degree level, before moving to London to start a new life after a failed relationship. One Sunday afternoon while she was away from her office work, Amy travelled to Stag Lane Aerodrome in North London, where she was immediately captivated and enthralled by the aircraft she saw. Amy was determined she was going to fly, and even though flying was the preserve of the rich and famous, she persevered using money supplied by her father.

She gained a number of certificates including a ground mechanics qualification and an aviator’s certificate before going on to gain her pilots “A” Licence, on 6th July 1929. Ignoring the ridicule she was targeted with by the media, Amy began to fly, taking solo flights to her home town and across the United Kingdom.

Amy’s biggest challenge came when she decided to fly solo to Australia. Plotting the most direct route from England, she would cross some of the world’s most inhospitable landscapes, meaning she would have to be airborne for many hours at a time, with no accurate weather reports or radio contact with the ground. Fuel would be supplied en-route, and it was therefore imperative that she made each stop on time in order to achieve her goal. Before long, the ridicule stopped and the media began to take serious notice of what she was doing.

They began to praise her, call her “Wonderful” and compare her to Charles Lindbergh. On May 24th 1930, she finally touched down in her second-hand de Havilland DH.60 Gipsy Moth, an aircraft she had called ‘Jason‘. She landed in Australia, in a time that was sadly outside of the previous record set by the Australian aviator Bert Hinkler in 1928.

Nevertheless Amy was still an aviation heroine, and was welcomed and revered across the world. Now Amy really had the bug, and flying would become a series of challenges, each as daring as the last. A year later in 1931, she would fly with her mechanic and friend, Jack Humphreys, to Tokyo. Together they would set a new record from Moscow to Japan. Amy then fell in love with another pioneering aviator, Jim Mollison, in 1932, a relationship that bonded two like-minded people with a common interest, and they began many journeys flying together. But Amy, still determined to achieve great things, also continued with her solo efforts.

She set another record flying from London to Cape Town in 1933, and then flew across the Atlantic with her husband, being given a tumultuous reception in America. Amy and Jim then took part in the MacRobertson Air Race, a gruelling air race that took competitors from Great Britain across the world to Australia. Sadly, part way across, engine trouble forced the couple to retire from the race, much to their frustration.

In 1936, just six years after achieving her pilots licence, Amy undertook her last record-breaking flight when she flew from England to South Africa setting yet another new world record.

In the years before the Second World War, Amy turned away from record-breaking flights and began her own business ventures. She carried out modelling projects using her good looks and personality to model clothes by Elsa Schiaparelli, the Italian fashion designer, another prominent and influential woman of the inter-war years. But flying was never far from her heart and with the outbreak of war, both the draw to serve her country and to fly, were too much, and she joined the Air Transport Auxiliary service In 1940.

Ferrying aircraft around the country, Amy dutifully carried out this work until January 5th 1941. On this day she was asked to take an Airspeed Oxford from Blackpool to RAF Kidlington, in Oxfordshire. Sadly, Amy and her passenger never made their destination. For some reason Amy was flying way off course, over the east coast of England rather than down the west coast or across central England, bot more direct routes. Over the North Sea, a few miles off-shore off Herne Bay, an aircraft was heard, and a parachute was seen falling from the snowy sky. A ship, HMS Haslemere raced toward the downed crew but even after frantic searches, neither of them could be found.

The commander of HMS Haslemere, Lt. Cmdr. Walter Fletcher, himself dived into the icy waters to search for survivors, but he couldn’t locate anyone, and sadly perished as a result of the extremely cold water. For his bravery and determination he was posthumously awarded the Albert Medal, an award given for extreme acts of gallantry, and the highest honour until the introduction of the George Cross in 1940.

Shortly after, personal items belonging to Amy along with parts of her aircraft were washed up on the nearby shores, strengthening the argument that it was indeed Amy’s aircraft that had come down. However, why she was flying where she was, and how she died, both remained a mystery, as does the whereabouts of her Airspeed Oxford aircraft.

Conspiracy theories were not slow in forthcoming. Ranging from secret missions to a victim of friendly fire, secret agents and covert operations were all banded about. Sailors on board HMS Haslemere believe she was sucked into the spinning propellers of the ship, a claim that is certainly plausible but not as yet substantiated.

The exact cause why she was so far off course and what caused her aircraft to crash has never been satisfactorily identified and continues to remain a mystery to this day. A vast number of plaques, buildings and statues have been dedicated in Amy’s honour, Schools and public buildings have been named after her, even aircraft have been called ‘Amy Johnson’ after the intrepid flyer. Her portrait has been displayed on tail fins and her home town of Hull have dedicated a number of structures and buildings to her, and the corridors of educational establishments resonate to the sound of her name. In Herne Bay, a life-size bronze stature was erected and unveiled jointly by HRH Prince Michael of Kent and Tracey Curtis-Taylor (a modern-day aviator herself embroiled in media attention) on 17th September 2016 to mark the 75th anniversary of Amy’s untimely death.

A bronze statue, it was designed by Stephen Melton, and sponsored by a number of local and national businesses. Nearby to the statue is a wooden bi-plane bench, also as a commemorative feature not only to Amy Johnson but all those who served in the Air Transport Auxiliary Service during the war. There has been much written about Amy Johnson’s life, her achievements and the records she set. She was indeed a remarkable woman, one whose determination proved that dreams can come true, and one whose dramatic life was tragically taken away from her at such a young age. She achieved many, many great things and is a superb role model to all, especially to women and aviators alike.

From Herne Bay, you can continue on to another trail of aviation history, eastward toward the coastal towns of Margate and Ramsgate, to Manston airport. Formerly RAF Manston, it is another airfield that is rich in aviation history, and one that closed with huge controversy causing a great deal of ill feeling amongst many people in both the local area and the aviation fraternity. More recently in 2020, a move was made to reopen the site for air traffic again, we await a firm decision about that. However, on the last stop on this trail, we head west to the Hoo Peninsula. Here we visit the former RAF/RFC Allhallows, an airfield that has long gone. Primarily a World War One site, it was reopened as an emergency lading ground in the Second World War.

RFC/RAF Allhallows. (1916-1935).

By Mitch Peeke.

The operational life of this little known Kent airfield began in the October of 1916, a little over two years into World War 1. Situated just outside the Western boundary of Allhallows Village, the airfield was bounded to the North by the Ratcliffe Highway and to the East by Stoke Road. Normally used for agriculture, the land was earmarked for military use in response to a direct threat from Germany.

Toward the end of 1915 and into 1916, German Zeppelin airships had begun raiding London and targets in the South-east by night. At a height of 11,000 feet, with a favourable wind from the East, these cigar-shaped monsters could switch off their engines and drift silently up the Thames corridor, to drop their bombs on the unsuspecting people of the city below, with what appeared to be impunity.

Not surprisingly, these raids caused a considerable public outcry. To counter the threat, street lights were dimmed and heavier guns and powerful searchlights were brought in and Zeppelin spotters were mobilised. Soon, some RFC and Royal Naval Air Service squadrons were recalled from France and other, specifically Home Defence squadrons, were quickly formed as the defence strategy switched from the sole reliance on searchlights and anti-aircraft guns, to now include the use of aeroplanes. Incendiary bullets for use in aircraft were quickly developed, in the hope of any hits igniting the Zeppelins’ highly flammable lifting gas and thus bringing down these terrifying Hydrogen-filled German airships.

No. 50 Squadron RFC, was founded at Dover on 15 May 1916. Quickly formed in response to the Zeppelin threat, they were hastily equipped with a mixture of aircraft, including Royal Aircraft Factory BE2’s and BE12’s in their newly created home defence role. The squadron was literally spread about trying to cover the Northern side of the county, having flights based at various airfields around Kent. The squadron flew its first combat mission in August 1916, when one of its aircraft found and attacked a Zeppelin. Though the intruder was not brought down, it was deterred by the attack; the Zeppelin commander evidently preferred to flee back across the Channel, rather than press on to his target.

At the beginning of October 1916, elements of 50 Squadron moved into Throwley, a grass airfield at Cadman’s Farm, just outside of Faversham. This was to become the parent airfield for a Flight that was now to move into another, newly acquired grass airfield closer to London; namely, Allhallows. On 7 July 1917 a 50 Squadron Armstrong-Whitworth FK8 successfully shot down one of the big German Gotha bombers off the North Foreland, Kent.

In February 1918, 50 Squadron finally discarded its strange assortment of mostly unsuitable aircraft, to be totally re-equipped with the far more suitable Sopwith Camel. 50 Squadron continued to defend Kent, with Camels still based at Throwley and Allhallows. It was during this time that the squadron started using their running dogs motif on their aircraft, a tradition which continued until 1984. The design arose from the squadron’s Home Defence code name; Dingo.

Also formed at Throwley in February of 1918, was a whole new squadron; No. 143, equipped with Camels. After a working-up period at Throwley, the complete new squadron took up residence at Allhallows that summer, the remnants of 50 Squadron now moving out.

RFC Allhallows had undergone some changes since 1916. When first opened, it was literally just a mown grass field used for take-off and landing. Tents provided accommodation for mechanics and such staff, till buildings began to appear in 1917. The first buildings were workshops and stores huts, mostly on the Eastern side of the field, on the other side of Stoke Road from the gates. The airfield itself was never really developed, though. No Tarmac runway, no vast Hangars or other such military airfield infrastructure was ever built.

On 1st April, 1918, the RFC and the RNAS were merged to become the RAF. 143 Squadron and their redoubtable Camels continued their residence at what was now RAF Allhallows even after the Armistice. In 1919, they re-equipped with the Sopwith Snipe, but with the war well and truly over, the writing was on the wall. They left Allhallows at the end of that summer and on October 31st, 1919; 143 Squadron was disbanded.

Their predecessors at Allhallows, 50 Squadron, were disbanded on 13th June 1919. An interesting aside is that the last CO of the squadron before their disbandment, was a certain Major Arthur Harris; later to become AOC-in-C of RAF Bomber Command during World War 2.

The Allhallows was presented by the Airfields of Britain Conservation Trust. The former airfield lies beyond the trees. (Photo by Mitch Peeke).

Now minus its fighters, RAF Allhallows was put into care and maintenance. It was still an RAF station, but it no longer had a purpose. The great depression did nothing to enhance the airfield’s future, either. But it was still there.

In 1935, a new airport at Southend, across the Thames Estuary in Essex, opened. A company based there called Southend-On-Sea Air Services Ltd began operating an hourly air service between this new airport and Rochester, here in Kent. They sought and were granted, permission to use the former RAF Allhallows as an intermediate stop on this shuttle service. Operating the new twin engined Short Scion monoplane passenger aircraft, each flight cost five shillings per passenger. Boasting a new railway terminus, a zoo and now a passenger air service, Allhallows was back on the map!

Alas, the new air service was rather short-lived. The service was in fact run by Short Bros. and was used purely as a one-season only, testing ground for their new passenger plane, the Scion. At the end of that summer, the service was withdrawn. As the newly re-organised RAF no longer had a use for the station either, it was formally closed. Well, sort of.

The land reverted to its original, agricultural use. But then, four years later, came World War 2. The former RAF station was now a declared emergency landing ground. In 1940, the RAF’s Hurricanes and Spitfires fought daily battles with the German Luftwaffe in the skies over Allhallows, as the might of Germany was turned on England once again, in an attempt at a German invasion. That planned hostile invasion never came to fruition thankfully, but in 1942/43 came another, this time, friendly invasion. America had entered the war and it wasn’t long before the skies over Allhallows reverberated to the sound of American heavy bombers from “The Mighty Eighth.” It wasn’t long before the sight of those same bombers returning in a battle-damaged state became all too familiar in the skies above Allhallows, either.

On 1st December 1943, an American B 17 heavy bomber, serial number 42-39808, code letters GD-F, from the 534th Bomb Squadron of the 381st Bombardment Group; was returning from a raid over Germany. She was heading for her base at Ridgewell in Essex, but the bomber had suffered a lot of battle damage over the target. Three of her crew were wounded, including the Pilot; Harold Hytinen, the Co-Pilot; Bill Cronin and the Navigator; Rich Maustead.

B-17 42-39808 of the 534BS/381BG [GD-F] based at RAF Ridgewell, crashed landed at Allhallows following a mission to Leverkusen on 1st December 1943 . The aircraft was salvaged at Watton, all crew returned to duty. (@IWM UPL 16678)

Tired from the long flight, fighting the pain from his wounds and struggling to keep the stricken bomber in the air, Hytinen chose to crash-land his aircraft at the former RAF station, Allhallows. Coming in roughly from the South-east, he brought her in low over the Rose and Crown pub, turned slightly to Port and set her down in a wheels-up landing along the longest part of the old airfield. All ten crew members survived and later returned to duty. The USAAF later salvaged their wrecked aircraft.

That incident was the last aviation related happening at the former airfield. In 2019, the Airfields of Britain Conservation Trust erected a memorial to the former RAF station, in the car park of the Village Hall. No visible trace of the airfield remains today, as the land has long since reverted to agriculture, but the uniform badge of the nearby Primary School, features a Sopwith Camel as part of the design of the school emblem.

RAF Allhallows is yet another part of the UK’s disappearing heritage, but although it has long gone, it will be long remembered; at least in the village whose name it once bore.

Editors Note: Allhallows, or to be more precise ‘Egypt Bay’ also on the Hoo Peninsula and a few miles west of Allhallows, was the location of the death of Geoffrey de Havilland Jnr., when on 27th September 1946 he flew a D.H. 108, in a rehearsal for his attempt the next day, on the World Air Speed record. He took the aircraft up for a test, aiming to push it to Mach: 0.87 to test it ‘controllability’. In a dive, the aircraft broke up, some say after breaking the sound barrier, whereupon the pilot was killed. The body of Geoffrey de Havilland Jnr. was days later, washed up some 25 miles away at Whitstable, not far from another air speed record site at Herne Bay – his neck was broken.

Our next stop along this trail of the North Kent coast is another of Britain’s airfields that has since disappeared under housing. It has a history going back to the heydays of aviation and the 1920s. It was, during the war, a fighter airfield and was home to many famous names including James “Ginger” Lacey DFM and Squadron Leader Peter Townsend. A number of RAF squadrons used the site, as did American units in the build up to D-day. A wide range of aircraft from single engined biplanes to multi-engined fighters and even air-sea rescue aircraft could have been seen here during those war years. Gravesend was certainly a major player in Britain’s war time history and thanks to Mitch, we can visit the site once more.

RAF Gravesend

Gravesend aerodrome was born during the heyday of public interest in aviation in the late 1920’s and early 1930’s. The original site was nothing more than two fields off Thong Lane in Chalk, which was used by some aviators of the day as an unofficial landing ground. One such pilot was the Australian aviator Captain Edgar Percival, who often landed his own light aircraft there when visiting his brother, a well-known Doctor in Gravesend. It is widely thought that it was Percival, who was after all a frequent user of those fields, who first suggested the actual building of an airport there.

Whether he did or whether he didn’t, the two men who founded the airport’s holding company, Gravesend Aviation Ltd., in June of 1932, were Mr. T. A. B. Turnan and Mr. W. A. C. Kingham. A local builder, Mr. Herbert Gooding, was engaged to build the Control Tower/Clubhouse building. In September of that year, with the construction work well advanced, Herbert Gooding and a man named Jim Mollison (the husband of the British aviatrix Amy Johnson), joined the Board of Directors of Gravesend Aviation Ltd.

The Mayor of Gravesend, Councillor E. Aldridge JP, officially opened the newly constructed airport as “Gravesend-London East”, on Wednesday 12th October 1932. To mark this Gala occasion, the National Aviation Air Days Display Team, led by Sir Alan Cobham, visited the new airport and gave flying demonstrations to thrill those people present. Also on display for visitors was a curious flying machine called the Autogiro, a sort of cross between a helicopter and a small aircraft, that had been built for a Spanish aviator by the name of Senor Cierva.

At the time of its opening, Gravesend airport covered 148 acres. Its two 933 yard-long runways were grass and the airfield buildings comprised the combined Control Tower/Clubhouse, two smallish barn-style hangars and some other, small ancillary workshop and stores buildings. Located in open countryside on the high, relatively flat ground on the western side of Thong Lane, between the Gravesend-Rochester road and what is now the A2 (Watling Street), Gravesend airport boasted an Air-Taxi service and a flying school among its amenities.

In November of 1932, just one month after the airport’s opening, Herbert Gooding took over as Managing Director of Gravesend Aviation Ltd. It seems likely that Mr. Gooding had effectively been “saddled” with the airport that he’d largely built. The original Directors, Messrs. Turnan and Kingham, possibly had run out of cash with which to pay Mr. Gooding for his construction work. They disappeared at this time, probably having paid Mr. Gooding with their own company shares. Jim Mollison, though married to Amy Johnson, had never been anything more than a “sleeping” director anyway, so it fell solely to Gooding to try to recoup his investment by making the airport a commercial success.

The original idea behind the airport had been to encourage the rapidly expanding European airlines to use Gravesend as an alternative London terminal to the often-fogbound Croydon airport, and this, Gooding now set out to accomplish. Although a number of airlines such as KLM, Swissair, Imperial Airways and even Deutsche Lufthansa did indeed make use of Gravesend, they didn’t utilise it on anything like the scale that had been hoped for. Perhaps it was thought at the time that Gravesend just wasn’t quite close enough to London, geographically.

Then in 1933, a year after the airport had been officially opened; Captain Edgar Percival established his aeroplane works in the small hangar next to the flying school. It was from here that he started to turn out the Percival Gull and Mew Gull aircraft. These were possibly the finest light and sports aeroplanes respectively, of their day, and in fact pilots flying these aircraft set many inter-war aviation records. Such pilots, for example, as Alex Henshaw, (who later became a Spitfire test pilot), Sir Charles Kingsford-Smith, Amy Johnson, and another well-known aviatrix, Jean Batten, as well as Edgar Percival himself.

During this time, a much larger, third hangar had been constructed by A.J. & J. Law Ltd. of Merton, alongside the existing two. This new hangar, forever referred to as the “Law hangar”, was 130 feet wide and 100 feet long, with integral offices and workshops running down each of its two sides. The Law hangar was completed in the early part of 1934 and prominently bore the legend “GRAVESEND LONDON EAST” above the hangar doors.

In December of 1936, Captain Percival moved his business to Luton. This may have seemed like a disaster for Gooding and his airport at the time, but as luck would have it, a company called Essex Aero Ltd., moved into Percival’s vacated premises almost immediately and stayed at Gravesend, building a thriving business from aircraft overhaul and maintenance, though their real forte was the preparation of racing aircraft and the manufacture of specialist aircraft parts.

Business at Gravesend airport was positively booming when Gooding sold the place to Airports Ltd., the owners of the recently built Gatwick airport. It was felt that if anyone could make a proper commercial success out of using Gravesend for its originally intended purpose, these people could. They certainly tried, but in the end sadly, even they couldn’t; and they quickly offered the site to Gravesend Borough Council, for use as a municipal airport. There followed protracted negotiations over terms, price, etc., all of which were suspended when, because of the increasingly ominous rumblings from Adolf Hitler’s Germany, the Air Ministry stepped in.

It was the expansion of the Royal Air Force that ultimately saved Gravesend. In 1937, No 20 Elementary and Reserve Flying Training School was established at Gravesend to train pilots for the RAF and the Fleet Air Arm.

The training of service pilots began in October of 1937. The school operated the De Havilland Tiger Moth and the Hawker Hart at that time. Accommodation for the instructors and the student pilots wasn’t exactly salubrious. For the most part, they used the clubhouse, together with rooms in some of the local houses.

Meanwhile, as the trainee service pilots learned their craft daily, (and not without accident!) the civil aviation side of Gravesend continued, with record attempts to the fore. In 1938, the twin-engined De Havilland Comet, G-ACSS that was used to set a record for the flight to New Zealand and back, was fully prepared for its successful record attempt by Essex Aero, as was Alex Henshaw’s Percival Mew Gull, which he used the following year to make a record-breaking flight from England to Capetown and back. Both of these record flights departed from Gravesend and were well publicised at the time.

The origin of the Hawker Hurricane. This visiting Hawker Fury MkI, K2062 belonging to No.1 Squadron, was photographed at Gravesend airport in 1938. Photo: S Parsonson via Gravesend Airport Research Group (Ron Neudegg).

But in the same year that Alex Henshaw set his record, war with Germany looked to be a near certainty and the Air Ministry duly set in motion the formalities needed to requisition Gravesend airport, in the increasingly likely event of war.

When war indeed came that September, No 20 E&RFTS was relocated, Airports Ltd surrendered their lease to the Air Ministry and the RAF duly took over Gravesend airport as a satellite fighter station in the Hornchurch sector. Essex Aero however, stayed; taking on a vast amount of contract work for the Air Ministry. Among the items they soon found themselves making, were fuel tanks for Spitfires.

The first fighter squadron to be based at what was now RAF Gravesend was 32 Squadron, who moved in with their Hurricanes in January of 1940. They were followed by 610 (County of Chester) Squadron with their Spitfires, who helped cover the Dunkerque evacuation. Following the deaths in action of two successive commanding officers within a short space of time, 610 Squadron was moved to Biggin Hill in July and 604 Squadron moved into RAF Gravesend temporarily with their Bristol Blenheims, whilst training as a night fighter unit. Also on temporary detachment at this time from their usual base at Biggin Hill, were the Spitfires of 72 Squadron.

It was during this period that the two decoy airfields at Luddesdown and Cliffe were completed, to help protect Gravesend. It was thought to have been an obvious matter to the Germans that the RAF would take over the airport at the commencement of hostilities. After all, the Germans certainly knew that Croydon airport was now a fighter station.

Accommodation was always to remain something of a problem at Gravesend. The clubhouse of course had some rooms, but nowhere near enough to house an operational fighter squadron’s complement of pilots, let alone the ground crews, station maintenance crews, or even the administration staff. In the end, most pilots were billeted either in the Control Tower/Clubhouse accommodation, or at nearby Cobham Hall, the ancestral home of Lord Darnley. (In fact, Lord Darnley nearly lost his home during the Battle of Britain. Not to German bombs, but to the hi-jinks of some of 501 Squadron’s pilots, who nearly burned the place down letting off steam on one drunken evening!).

The station’s Ground crews were billeted at either the Laughing Waters Roadhouse (the original site of which is now occupied by The Inn on the Lake) about one mile up Thong Lane, or just the other side of Watling Street in somewhat spartan accommodation encampments, where “home” was a village of Nissen huts hidden in Ashenbank Woods. (Nothing remains of these encampments today save for three of the large underground Air Raid Shelters). Those who could not be accommodated in the huts were billeted in Bell tents pitched around the airfield perimeter. No doubt this was fine during the spring and summer, but not so good during the winter.

On 27th July 1940, 604 and 72 Squadrons moved out and 501 Squadron took up residence, being based there throughout the greater part of the Battle of Britain period, during which time the sector boundary was changed, so that Gravesend then came under the aegis of Biggin Hill. 66(F) Squadron arrived to relieve 501 in September, but as the Battle of Britain raged and German bombs mercilessly pounded Fighter Command’s other airfields, Gravesend got off lightly, especially compared to the sector command station at Biggin Hill.

Pilots of 66(F) Squadron in the clubhouse at RAF Gravesend in September 1940. From left to right, standing: Flight Lieutenant Bobby Oxspring, Squadron Leader Rupert Leigh and Flight Lieutenant Ken Gillies. From left to right, seated: Pilot Officer C Bodie, Pilot Officer A Watkinson, Pilot Officer H Heron, Pilot Officer H (Dizzy) Allen, Hewitt (Squadron Adjutant), Pilot Officer J Hutton (Squadron Intelligence Officer) and Pilot Officer Hugh Reilley. Photo: The Times, via Gravesend Airport Research Group (Ron Neudegg).

Although the Luftwaffe reconnaissance branch belatedly photographed Gravesend airfield again in November of 1940 and updated their target identification sheet, (Gravesend was given the target designation G.B. 10 89 Flugplatz) one can only conjecture that prior to that, the decoy site at Cliffe must have performed its role superbly. The fact that only two German bombs ever landed on RAF Gravesend during the entire Battle of Britain period, and then only in passing, would seem to support this, as the decoy airfield at Cliffe was bombed many times. Each time the Germans bombed the decoy airfield at Cliffe, with its equally fake Hurricanes dispersed around it, RAF work gangs would fill in the craters. This activity in turn seemed to convince the Germans that Cliffe ought to be bombed again. In the meantime, the real fighter station at Gravesend was left virtually unmolested. On the only occasion when Gravesend airfield was specifically targeted, the Germans bombed the wrong side of Thong Lane and missed the airfield completely.

Given the fact that during the pre-war period, Lufthansa flights had regularly made use of Gravesend airport to deposit passengers, it seems all the more astonishing that the Luftwaffe were seemingly unable to find the place again when distributing their stock of bombs. Ultimately, the night decoy airfield at Luddesdown also attracted little attention from the Luftwaffe either.

Piece of paper from the Sergeants Mess at RAF Gravesend in 1940, bearing the signatures of some of the Sergeant Pilots of 501 Squadron. Clearly legible is that of James “Ginger” Lacey DFM, who became the top-scoring RAF Battle of Britain pilot, and Geoffrey Pearson, (last one down, right hand column) who was killed in combat, aged just twenty-one. Via Kent County Library Services.

In October, at Churchill’s insistence, 421 Flight was formed at Gravesend from a nucleus of 66(F) Squadron’s pilots. In recognition of their origin, 421 Flight’s aircraft wore the same squadron identification letters as 66(F) Squadron’s aircraft, (LZ) but with a hyphen between them. Their job was to act as singleton flying observers to incoming enemy raids. A job with rather a high risk element!

With the manifest failure of the Luftwaffe’s daylight offensive, 66(F) Squadron and 421 Flight moved out of Gravesend at the end of October, and 141 Squadron with their Boulton-Paul Defiants moved in. They were joined soon afterwards by the Hurricanes of 85 Squadron, a former day-fighting unit led by Squadron Leader Peter Townsend, to take up the challenging role of night-fighting. These two squadrons stayed at Gravesend throughout the remainder of 1940. Townsend’s squadron moved out just after New Year, leaving 141 Squadron as the resident unit into the spring of 1941, though another Defiant-equipped squadron, 264 Squadron, joined them for a short time while the Luftwaffe continued with their efforts to destroy London by night. When the Luftwaffe finally abandoned that enterprise late in May of 1941, the night fighters moved out and Gravesend once again saw the Spitfires of several different day-fighting squadrons based there to carry out offensive sweeps over occupied France.

In 1941, the height of the control tower was raised by one level and during more major works that were carried out during 1942 and 1943, the two existing 933-yard grass runways were extended. The north-south runway was lengthened to 1, 700 yards and the east-west runway to 1, 800 yards. The station’s storage facilities were also enlarged and runway lighting was finally installed, as was Summerfield runway tracking, in an attempt to combat the autumn and winter mud. Also enlarged was the ground crew accommodation camp at nearby Ashenbank Wood.

Spitfire LF VB BM271/SK-E Kenya Daisy of No 165 Squadron returns to its dispersal at Gravesend on 16 October 1942. (© IWM CH 7686)

In December of 1942, 277 Squadron, an RAF Air-Sea Rescue unit, duly took up residence. An unusual unit inasmuch as they flew a variety of aircraft at the same time. They had the amphibious Supermarine Walrus, which one would expect given the nature of their work, but they also had Westland Lysanders, Boulton-Paul Defiants and Spitfires. They were stationed at RAF Gravesend for a total of sixteen months, making them the record holders for the longest stay of any squadron at Gravesend.

The enlargement and improvement of the station had made possible the accommodation of three squadrons and in fact, three fighter squadrons of the USAAF were stationed at Gravesend for a while. Having longer and better runways also meant that battle-damaged heavy bombers returning from raids on Germany now stood a reasonably good chance of making a successful emergency landing at Gravesend, too.

In the early part of 1944, 140 Wing of the 2nd Tactical Air Force was based at Gravesend with their Mosquito fighter-bombers. The Wing comprised two Australian squadrons and one New Zealand squadron. The Wing’s task was that of “softening up” targets prior to the Normandy landings. With the success of the D-Day landings, 140 Wing continued their operations but shortly after D-Day, a new menace totally curtailed the station’s flying activities.

On 13th June, the very first V-1 “Doodlebug” landed at nearby Swanscombe, having flown almost directly over RAF Gravesend. In the coming weeks, the sheer numbers of these high speed pilot-less rocket-bombs passing very close to, if not actually over the RAF station, meant that flying from there was now a hazardous undertaking. 140 Wing moved out.

With the aircraft gone, RAF Gravesend became a command centre for the vast number of barrage balloon units that were brought into the surrounding area to help deal with the V-1 menace. The station also became a local air traffic control centre, to ensure that no friendly aircraft fell foul of the balloons. The V-1 campaign petered out toward the end of 1944 as the advancing Allied armies rapidly overran the launching sites and five months into 1945, the war ended.

With the end of the war, Gravesend was put into a care and maintenance state and surplus service equipment was stored in the Law hangar for a while. Only Essex Aero continued to work there, as they had throughout the war, eventually taking over the Law hangar, too.

Although Essex Aero tried hard to carry on from where they had left off just before the war, the nature of civilian aircraft and aviation had changed a great deal. Air racing and record-breaking was no longer in the public eye, as they had been in the thirties. The Air Training Corps now ran a gliding operation from Gravesend, and Essex Aero continued to make specialist aircraft parts and revolutionary Magnesium Alloy products, but the biggest problem facing them was the fact that Gravesend Borough Council steadfastly refused to grant the necessary planning permission that would allow the wartime runway extensions to be properly incorporated into the post-war aerodrome.

In April 1956, unable to work on the more numerous but ever-larger civilian aircraft types, because the pre-war dimensions of the airfield would not permit them to land there, Essex Aero went into liquidation.

In June of 1956, the Air Ministry relinquished their lease on the airfield and demolition and clearance work began in 1958. First to go were the two Barn-style hangars. The Law hangar was dismantled and re-erected on Northfleet Industrial Estate, minus its offices and workshops, where it served as a bonded warehouse until the late 1990’s. The rest of the buildings, except the Control Tower/Clubhouse, which became the site offices of the developers, were bulldozed to make way for a massive new housing estate, known today as Riverview Park. In 1961, the control tower was finally demolished and the last houses were built where it had stood. No visible trace of the once vital fighter station was left to remind anyone of what had been there.

A final view to the south from the Control Tower of Gravesend aerodrome, prior to its demolition in 1961. The stacks of bricks piled up on the old hangar floors are for the construction of the houses that made up the final stage of the development. These houses were built where the airport buildings once stood, thus removing the last visible trace of this once vital fighter station. Photo: P Connolly, Gravesend Airport Research Group, via Ron Neudegg.

Yet RAF Gravesend had one last, hidden, reminder of its presence left to reveal. In April of 1990, many of the houses on the estate had suddenly to be evacuated when an unusual item was found buried in one of the gardens.

Fifty years previously, in June of 1940, the prospect of a German invasion looked very real. As we have seen, measures were taken to protect the airfield such as the setting up of the two decoy fields and the building of perimeter defence positions. Another, since totally forgotten measure, was the laying of “pipe mines” that would be exploded to deny the use of the airfield to the Germans should they succeed in invading England. It was one of these mines that had been found.

It transpired that Dolphin Developments Ltd, the building contractors who had constructed Riverview Park, were completely unaware of the presence of these mines and had happily built the entire estate on top of them. The original plans of the minefield were finally procured and the Royal Engineers were called in to locate and remove the rest of the mines. Once this operation had been successfully completed, the very last wartime vestige of RAF Gravesend had been removed.

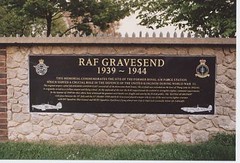

Yet the story of RAF Gravesend doesn’t quite end there. When “Cascades” Leisure Centre was built on the eastern side of Thong Lane, almost opposite where the main entrance to the RAF station once was, they put up a plaque of remembrance to the station and the pilots who had lost their lives flying from there during the Battle of Britain. The original plaque was initially located on an outside wall. Unfortunately, the name of the first of those pilots, Phillip Cox of 501 Squadron, was somehow shamefully omitted.

The plaque stayed there, despite the inglorious error, for many years until 2003; when Sunday 2nd March saw the dedication of an all-new memorial to commemorate RAF Gravesend, the part it played in the Battle of Britain and a new plaque commemorating all fifteen of the pilots who died in combat whilst flying from the airfield during the battle.

The memorial itself is a large Black Marble plaque with Gold lettering, bearing both the RAF and the Fighter Command crests; one set either side of the gilded legend “RAF GRAVESEND”. The plaque is set into a purpose-built, stone-clad wall outside the gates of the Leisure Centre, and faces the houses that now stand close to where the airfield’s main entrance once was. The new plaque, finally listing all fifteen pilots, can now be found on the wall in the reception of the Leisure Centre, along with other displays which include a brief history of the airfield and the two squadrons that flew from there during the Battle of Britain. A few years later, photographs of all of the fifteen pilots were put into a collective frame and added to the display.

There was a full dedication ceremony flanked by standard-bearing parties of Air Cadets from the two local units, 402 Gravesend and 2511 Longfield Squadrons, led by Flight Lieutenant Tony Barker, the Commanding Officer of 2511 Squadron. Reverend Group Captain Richard Lee, lead the service of dedication and thanksgiving. Also included was a short history of the airfield read by Ron Neudegg, a founder of the Gravesend Airport Research Group. The Right Honourable Chris Pond, MP for Gravesham, then read the lesson, before Sergeant Steve Maher of the Central Band of the Royal Air Force sounded the ‘Last Post’ on the bugle. At last was paid a truly fitting tribute to a once vital fighter station and the fifteen pilots who lost their lives while flying from there.

One last, but still little-known fact however, is that if you know where to look, you will find the graves of two of those fifteen pilots quite nearby, in Gravesend Cemetery. The graves are those of Pilot Officer John Wellburn Bland of 501 Squadron, and Pilot Officer Hugh William Reilley of 66(F) Squadron.

The fortunes of the place where the pilots used to relax, The White Hart, have been as up and down as the aircraft those pilots flew. The pub the airmen knew was opened on October 19th 1937, just as the RAF moved into Gravesend Airport and started to train service pilots there. It was a new building, replacing one that had stood there for over a century, which was itself a replacement of the much older original building. The new White Hart was owned by Truman’s Brewery and Daniel Pryor was the first Landlord of this newly built inn. Daniel’s association with the airfield’s pilots probably started with those being trained at No 20 E&RFTS. By the time Daniel’s Den was playing host to the pilots of 501 and later, 66(F) Squadrons’ pilots, a direct line had been set up from the airfield to the pub, to warn pilots of imminent air raids (and probably visits from high-ranking officers!). Daniel Pryor’s tenure lasted till 1943. After a succession of further Landlords, the building was demolished in 1999 to make way for the Harvester Pub and Restaurant that occupies the site today.

In what is surely a strange quirk of fate, more actually remains of the fake airfield at Cliffe marshes, despite the bombing, than the real one at Gravesend, today. At the site of the decoy airfield, the southwest and the western parts of the access track remain, as does the fake control point. The control point is accessible from the track and is a two-roomed, brick-built bunker with a concrete roof. The bunker is entered via a small, door-less corridor. The two rooms are at the end of the short corridor, one on each side. The left-hand room has light, due to a square hatch in the ceiling, the cover of which has long since been removed. The right-hand room is smaller and completely dark, as the whole bunker is window-less. There is nothing inside the bunker today except for a small amount of rubbish and the seemingly inevitable graffiti that adorns the walls. The three-quarter-mile-long grass runways that never actually were, are today home to grazing cattle.

The new memorial situated in Thong Lane, Gravesend, to commemorate the part played in the Battle of Britain by RAF Gravesend. Photo: Mitch Peeke.

Apart from the bunker, there is no lasting or purpose-built memorial to the part played by the dummy airfield, even though it saved untold damage being done to the real fighter station at Gravesend, not to mention the corresponding casualties that would have been sustained among the personnel stationed there. Sadly, RAF Cliffe is now but a little-known and seldom remembered place. Above all, like the vital fighter station it once protected, it is yet another example of this country’s disappearing heritage.

By Mitch Peeke.

Editors note: in 2016 the Airfields of Britain Conservation Trust erected an airfield marker outside of Cascades Leisure Centre to commemorate and mark the location of RAF Gravesend.

Sources and further reading (Barnes Wallis)

*1 Photo from airshipsonline

*2 Photo from The Barnes Wallis Foundation

*3 The Mail online published a report on the discovery of a Highball bomb found in Loch Striven, Scotland in July 2017.

*4 Photo © IWM (CL 4322)

*5 The Independent news website– “Secrets of the devastation caused by Grand Slam, the largest WWII bomb ever tested in the UK.” Published 22/1/14 The Barnes Wallis Foundation website has a great deal of information, pictures and clips of Barnes Wallis. A list of memorials, current examples of both Upkeep and Highball bombs, and displays of material linked to Barnes Wallis, is available through the Sir Barnes Wallis (unofficial) website.

Sources and further reading (Air Speed Record)

*1 Guinness World Records website accessed 22/8/17.

*2 The Argus News report, Thursday November 8th 1945 (website) (Recorded readings quoted in this issue were incorrect, the correct records were given in the following day’s issue).

*3 The Argus News report, Thursday November 9th 1945 (website)

*4 Photo from Special Hobby website. The RAF Manston History Museum website has details of opening times and location. The Manston Spitfire and Hurricane Memorial museum website has details of opening times and location. Sources and further reading (Amy Johnson): The Amy Johnson Arts Trust has a wealth of information about Amy and her links to aviation. Their website is worth visiting.

Sources and further Reading (RAF/RFC Allhallows)

Airfields of Britain Conservation Trust website

Southend Timeline website

American Air Museum website

Imperial War Museum website

Village Voices Magazine

Allhallows Life Magazine