The third and final part of this Trail around North Norfolk, takes in two further former USAAF airfields. Being in the more northern reaches of Norfolk, they share similar stories of tragedy and loss. Our first stop is an airfield that lives on – just – and was the home to only one major bomb group. This group led the way for the B-24, they took heavy loses and bore the brunt of B-17 crew jokes. Their loses were so high that unofficially, they became the ‘Jinx Squadron’.

Our first stop is Shipdham home to the ‘Flying Eightballs‘ followed by a short hop to Wendling, the most northerly of the American bases.

RAF Shipdham (Station 115)

On leaving RAF Watton, we travel north-east across the countryside to the small village of Shipdham, some 3.5 miles south of East Dereham. If you miss the turn, you will pass along the main road and a row of memorial trees dedicated to the parishioners of Shipdham who died in both World Wars. A list of those concerned is on a large board placed adjacent to the road. Turn back, return towards the village and take the left turn toward the airfield site. Opened in 1942, it was the first airfield to receive the Mighty 8th, who named it Station 115.

Shipdham was built during the period 1941-42 and opened as the first US heavy bomber airfield in Norfolk. It was built as a Class A airfield having three concrete runways, one of 2,000 yards, and two of 1,400 yards, each 50 yards wide. A standard perimeter track linked all three runways, the main one of which ran east-west.

The technical and administrative area was located in the south-eastern corner, the bombs store to the south-west, and the accommodation areas dispersed off to the south, unusually, between the two aforementioned sites. There were initially 50 concrete hardstands, but this increased later on to 55 as the airfield was updated. The majority of these hardstands (37) were the single pan style, whilst the remainder were the dual spectacle style.

Accommodation was built for around 3,000 personnel using a range of temporary buildings over nine different sites, with a further two sites, both sewage works, and a wireless transmitter site, also being located here . Shipdham unusually had three communal sites, two male and a WAAF, and many buildings were temporary in nature: Laing, Nissen, Thorn and some Hall huts. A further number of buildings were brick with both temporary and permanent designs in use.

The Watch Office (built to drawing 8936/40) was part timber and part concrete, a deviation from drawing 2423/40, and still stood, albeit in a very poor condition, at the time of visiting.

The first group to arrive here were the 319th BG, a group made up of twin-engined B-26 ‘Marauders’, who flew across the northern route of the Atlantic during September 1942. Their trip across was hazardous, many aircraft suffering as a result of the cold and closing winter months. Sent to Shipdham to begin training operations, they only remained here for around one month, being moved to RAF Horsham St. Faith in October, and with it vacating Shipdham for good. In their place came the main resident unit, the 44th BG known as the ‘Flying Eight Balls‘ bringing with them the mighty B-24 Liberators.

Shipdham’s Watch Office sites amongst the cranes and industrial buildings. (Just below the two cranes)

Activated on January 15th 1941, they were the USAAF’s first Liberator unit, becoming an operational training unit in February 1942, carrying out anti-submarine duties before making preparations for the European theatre. They moved from MacDill Field in Florida to Barkdale Field, Louisiana, and then onto Will Rogers Field in Oklahoma before setting off for England in October 1942. The three squadrons of the 44th, the 66th, 67th and 68th BS, were finally provided with aircraft and a full complement of aircrew at Will Rogers; however, this did not include the fourth and final squadron, the 404th BS, who were diverted to Alaska to protect the west coast against potential Japanese attacks. Being only three squadrons, the 44th BG would operate below full strength for almost six months until the replacement squadron, the 506th BS, would arrive. This weakened force would play its part in the 44th’s short and tragic history.

On September 4th, the ground echelons sailed on the Queen Mary, arriving in Scotland on the 11th. The first aircraft did not leave the US until later that same month, after which all personnel were gathered at their temporary base at Cheddington before moving off to Shipdham in October.

Once in England, the Liberators of the 44th were modified, flown to Langford Lodge, they were given scanning windows in the nose, the fitting of British IFF equipment, and improvement to the guns. The B-24s had been supplied with limiting ‘cans’ of ammunition rather than the much longer belt fed ammunition. Another adaptation at this point was the fitting of two .50 calibre machine guns in the nose, similar in style to those of the B-17.

On November 7th 1942, the ‘Flying Eight Balls‘ were put on limited combat status, with a small number of eight aircraft being sent on their first operational sortie. A diversionary flight, it was followed by four more sorties, of which only one involved any bombing at all. The 44th were not having a successful time though, the equipment they had been provided with was not protecting the crews from the extremely low temperatures found at high altitudes, several crewmen suffering from frostbite as a result.

By early December the last of the modified B-24s arrived back at Shipdham and the Group was back up to its three squadron strength. On the 6th December 1942, the group flew its first mission, a nineteen strong formation was sent to bomb the airfield at Abbeville-Drucat in France.

This mission would not go well. A diversionary attack, it would see the two squadrons the 66th and 67th called back, the abort signal did not however reach the 68th who unaware of the changes, carried on to the target. Being only six aircraft, they were woefully under protected, and after releasing their bombs over the target, were attacked by around thirty FW-190s. What resulted was devastating for the 68th, one aircraft was lost, Liberator #41-23786 piloted by 1st Lt. James Du Bard Jr. (s/n: 0-410225), along with its entire crew. Witness accounts from other crews say that as the aircraft went down, its guns continued to fire, the gunners of #786 staying at their respective stations even though their fate was sealed. As the pilot struggled to regain control and get the aircraft home, they managed to bring down two enemy aircraft before crashing into the sea themselves. For their actions and bravery, the entire crew were awarded the Silver Star.

In the attack on Abbeville-Drucat , every B-24 was hit by enemy cannon fire. Following a head on attack by fourteen FW-190s in waves of three or four, an exploding 20mm shell in the cockpit of ‘Victory Ship‘ #41-23813, badly injured both the pilot and co-pilot; but undeterred, 1st Lt. Walter Holmes Jr (s/n: 0-437615), managed to get home and land the aircraft even though he and his copilot, 2nd Lt. Robert Ager, were badly injured. For his brave action and determination to get home, he was awarded the first DFC for the group. Holmes would also go onto receive a DSC in the mission to Ploesti in August going on to complete his tour of duty later that same month.

A medical truck and ground personnel standby as B-24 Liberator #41-23813 “Victory Ship” returns from a mission. (IWM FRE 640)

A second attack to the same target was aborted, but during this mission one crewman suffered frostbite and had to have his arm amputated at the elbow. Then followed the third mission, and it proved just as disastrous for the 44th. A flight of 101 aircraft, a mix of B-17s and B-24s were sent to Romilly-sur-Seine, and of the 101 aircraft sent, only seventy-two made it to the target, the remainder being lost or aborting. From the 44th, only twelve of the twenty-one sent out made it through, and of these, one suffered a head on attack by a FW -190. The pilot Cap. Algene E. Key took evasive action but cannon shells ripped through the aircraft killing gunner S/Sgt. Hilmer Lund and seriously wounding two others. Key manged to fly the aircraft to the target and then home, even though it was badly damaged and difficult to fly. For his actions he was awarded the DSC.

The start of the war was not a good one for the 44th, many of those who came over were now in a state of shock, the extremely cold temperatures and determined fighters of the Luftwaffe both taking a toll on the crews. The early days of the 44th were difficult and the crews faced a very steep learning curve.

When the 44th’s sister group the 93rd BG departed for North Africa, the 44th’s three squadrons consisting of only nine aircraft each, accounted for the entire Liberator force in the European Theatre. Performance figures for the B-24s made it difficult to fly in tight formations, the faster speed of the B-24 also meant it ended up at the rear of the large formations and slightly higher. It was a difficult aircraft to fly and crews were finding it hard to maintain flight with the slower and lighter B-17s.

To counteract these problems they were given restricted fuel levels, a restriction that proved to be fatal on the January 3rd 1943 mission to St. Nazaire. With further aircraft aborting, only 8 aircraft reached the target and able to drop their bombs. On the way back, the leading B-17s took an incorrect heading, and the flight flew up the Irish Sea as opposed to crossing over southern England. Now desperately short of fuel they split up, searching for a safe haven. Some aircraft unable to locate an airfield, ran out of fuel, and had to land in fields with the expected results. Three crewmen were killed that day and seventeen were wounded, some dying later from injuries sustained in the crashes.

1943 had started as badly as 1942 had ended. Spirits were now low and over the next few weeks several aborted missions added to the misery of the 44th. With further losses in the few missions they flew, rumours spread of a ‘hard luck’ squadron, and questions were raised as to the suitability of the B-24 as a bomber. Things got so bad that the 67th was reduced to just three aircraft, with no sign of replacements of men or machine being delivered anytime soon.

Then came some good news, the fourth squadron the 506th, arrived in March 1943 raising the 44th to its full complement of four squadrons for the first time since leaving the United States. Manning these aircraft was going to be another challenge though, many of the gunners were ground crews retrained as aircrew, some were drafted in from other squadrons, often being crewmen who had ‘failed’ in their previous roles. The future didn’t look any better even with the full complement of staff.

The Eighth now looked toward night flying as a possibility, the 93rd, having returned from Africa, stopped flying in order to train in their new role, leaving the 44th to ‘carry the can’ once more. Reduced to diversionary raids, the 44th were sent to Kiel on May 14th 1943, carrying a large number of incendiaries. Flying behind the higher B-17s, they were easy pickings for the FW-190s who picked off five of the twenty-one sent out before they reached the target. However, the determination of the crews saw some aircraft both get through and bomb successfully, a determination that won the group their first Distinguished Unit Citation (DUC).

With another aircraft lost on the return leg, the 44th had taken yet another beating, apart from odd crewmen who had been on leave or indisposed, the entire 67th had now been wiped out, one-quarter of the 44th was gone. Those that were left became bitter, some refused to fly, some had breakdowns but many others became stronger and more determined to see this through. The strength of those left was fuelled by both the bitter feeling toward the B-17 crews who continually mocked them, referring to them as ‘the jinx unit’, and those in command who it was felt used them for Luftwaffe bait.

There then followed a short period of good luck. A raid on the Submarine repair depot at Bordeaux on May 17th 1943 saw the loss of only one aircraft. ‘Avenger II‘ #42-40130 suffered engine problems, and being too far from England to make it back, the pilot 1st Lt. Ray Hilliard and the crew, decided to try their luck in neutral Spain. Turning south, they landed at the airfield at Alhama de Aragon where they were interned spending the next three months at the pleasure of the Spanish, before being returned to England.

There next followed an operational intermission, the B-24s swapping ‘ops’ for low flying practice over the English countryside until, on June 26th, when they departed Shipdham for the warmer climates of North Africa. Here they would carry out bombing missions over Italy and southern Europe including the famous Ploesti Oil refinery raid in August, for which they took another hammering and earned a second DUC in August 1943.

In late August, the 44th began returning to Shipdham, with some detachments remaining in North Africa, this meant that the 44th was split between both England and North Africa, performing missions from both locations. A disastrous few months however, had taken further tolls on the crews, but camaraderie remained high and resilience strong.

On the night of 3rd/4th November 1943, 577 RAF bombers attacked Dusseldorf, and whilst losses were relatively light, Shipdham would play its part in one particular act of incredible heroism.

Flying in Lancaster LM360 was Flt. Lt. William ‘Bill’ Reid and his crew from 61 Sqn, RAF Syerston, near Newark. The aircraft was attached by a Bf 110 night fighter, on the outward leg of the flight. In the ferocious attack, the control systems were damaged, the rear gunner’s turret badly damaged and cockpit instruments were also damaged. The attack also left the aircraft’s windscreen shattered and Flt. Lt. Reid badly wounded in the head, shoulders and hands. Persevering, Reid continued on only to be raked by a second attack from an FW 190. Further damage was inflicted upon the aircraft which also killed the Navigator Flt. Sgt. J. Jeffries, and fatally injured the mid-upper gunner. To add insult to injury, the oxygen supply was put out of action, a potentially fatal situation, crews known to pass out from anoxia through the lack of oxygen.

Assisted by the Flight Engineer Sgt. J. Norris using a portable oxygen tank, Reid continued on using only his memory of the briefing notes to carry out his attack.

A successful raid was achieved, and Reid put the Lancaster on a course for home. Continued flak harassed the crew but soon England was reached and an airfield was sought. Shipdham came in to view, and with deteriorating health, Reid attempted a landing. His continued passing out through lack of blood prevented him from keeping their aircraft in the air alone, the navigator and bomb aimer coming to help as the stricken bomber made its way gingerly toward Shipdham.

On landing, the undercarriage gave way, and the Lancaster slid along, tearing parts away as it eventually ground to a halt.

For his actions that night, Flt. Lt. Reid was awarded the Victoria Cross, his citation in the London Gazette (14th November 1943) quoting “most conspicuous bravery”. His story can be read in Heroic Tales.

The winter of 1943/44 was one of the worst for the cold, ice and snow. England like most of Europe was snowed in and temperatures dropped dramatically. For the 44th, the new year would not bring any let up, and it started on yet another terrible note.

On January 13th, a training mission was organised for a new crew, who had only joined the group on the Christmas Eve, and were barely three weeks into their war. On this day, B-24 #42-7551 of the 68th BS piloted by 2nd Lt. Glenn Hovey, would come in on approach to Shipdham, a landing in which one of the engines was feathered to simulate one engine out. With flaps and gear down, the pilot overshot, banking to the left striking a tree causing the aircraft to crash. The ensuing fireball killed nine men instantly, the tenth 2nd Lt. Richard Sowers being taken to hospital where he died shortly after. For a rookie crew this was perhaps the worst possible cause of death.

Liberators, including a B-24 (#41-29153), ‘Greenwich’ of the 506th BS, 44th BG (pilot 1st Lt. Robert Marx) conducts a raid on a German airfield near Diepholz. February 21st 1944. This aircraft was subsequently lost on April 8th 1944, all the crew were taken prisoner. (Official U.S. Air Force Photo)

The extreme pressures placed of aircrew were beyond that imaginable, and for some, it was just too much. After having joined the 44th and flown since July 1943, for one pilot it all became too great, and on January 20th he sadly took his own life. Not a unique event by any means, but his death shows the great pressure that airmen were subjected to and for some it was simply a step too far.

The end of March and into April saw the poor weather continuing, with many missions being aborted. On April 1st, a mission to Grafenhausen was yet again cancelled, but B-24s of the 44th and 392nd did continue on. Unbeknown to them, they were way of course, and when they released their bombs it was the Swiss town of Schaffhausen that was beneath them, and not the Germany city. Ten aircraft were lost that day whilst Swiss papers reported the loss of thirty residents. The Nazi propaganda machine-made good use of this most unfortunate accident.

Only eight days later the ‘Eightballs’ would suffer their greatest loss of the war, April being the month that cost more in men and machines than any other month of the conflict. This was a month that put even Ploesti and Foggia in the dark. A mission to Brunswick was scrubbed as the town was shrouded in smoke, and so a secondary target was selected Langenhagen Aerodrome near Hanover in Germany.

Now for the first time, fitted with PFF, the B-24s flew toward the target. It was a cloudless and sunny day, an escort of P-51s were with the Liberators when suddenly, out of the sun, came a whole horde of enemy fighters. They struck from above and in front making a concentrated attack that took out eleven of the 44th’s group; forty-one airmen were killed that day with almost as many being taken prisoner.

For the remainder of the war the group attacked many high prestige targets, including airfields, oil refineries, railways, V-weapon sites, aided the Normandy landings and the breakout at St. Lo. They supported the ground forces in the Battle of the Bulge and attacked railway bridges, junctions and tunnels preventing German reinforcements arriving at the front.

With their last operational bombing sortie taking place on April 25th 1945, never again would they lose as many aircraft as they did during those three major raids. Bombing turned to food supplies and transit flights bringing home POWs from camps across Europe.

Then over May / June 1945, the various echelons began to depart Shipdham returning to the U.S., they had completed 343 missions using six different marks of B24. They had flown against submarine pens, industrial complexes, airfields, harbours and shipyards. Whilst in Africa they had flown in the Ploesti raid in Romania, the raid on Foggia and had helped in the invasion of Italy.

The Unit achieved one of the highest mission records of any B24 group for the loss of 153 aircraft, the highest loss of any B-24 group. They had taken the taunting of the B-17 crews, been called ‘Jinxed’ and had lost a lot of young men in the process. The 44th had paid the price, but they had earned two DUCs, a Purple Heart and numerous other medals for gallantry and bravery in the face of adversity.

The 44th and their home at Shipdham had well and truly written itself into the history books.

Following cessation of conflict the mighty 8th left Shipdham. The airfield became a POW camp closing in 1947, it then remained in care and maintenance until finally being sold off in 1963. Over the years it has been turned into agricultural premises with an industrial complex covering the technical area of the airfield. Fortunately, flying activity has managed to keep a small part of Shipdham alive with the Shipdham Aero Club utilising one of the remaining runways.

If you drive round the site to the industrial area, you can clearly see the remaining two hangers through the fence. Behind these are a small selection of dilapidated buildings from what was the technical site, including the control tower and operations block.

The tower is now a mere shell and in danger of demolition. For those not tempted to venture further, views of these can be seen from across the fields on the aero club side of the site. Further views reveal one runway covered in farm storage units, but the runway they sit on, remains intact.

This is a large site, much of which is now either agriculture or industrial, with what is left is in desperate need of TLC. Whilst there is a small part of this airfield alive and kicking, the more physical features cling on by their finger nails desperate for the care and attention they wholeheartedly deserve.

The club house at the aero club houses a small museum in memory of those who flew from here, with many pictures and personal stories it is one to add to the list of places to go.

I found this rare original footage of the 44BG taken at Station 115 on ‘You Tube’. This features a number of B-24s preparing for, and returning from, the November 18th Mission to Kjeller Airfield, Oslo (not the 19th as implied on the film). It also includes B24H #42-7535 ‘Peepsight‘ of the 506th crash landing after a mission.

The latter half of the film includes footage from 1944-45 noted by the change in the tail fin Bomb Group coding (Black stripe on white background as opposed to the black ‘A’ in a white circle). It would appear therefore to be a compilation of dates, but this aside, it is very much worth watching.

Shipdham was a relatively short-lived airfield, used by only one unit, the 44th Bomb Group, it saw many crews come and go and bore witness to some incredible actions. Whilst Shipdham lives on, the future of its buildings remain in doubt, the creeping industrial strong hold gaining in strength with each passing day. How long will it be before it sinks into obscurity and the brave actions of those who never returned are forgotten.

On leaving Shipdham go back to the village and head toward our next stop, RAF Wendling, where the 392nd were cited for their incredible bombing accuracy but losses were high.

RAF Wendling (Station 118)

On 15th January 1943, a new bomb Group was formed at Davis-Monthan Field in Arizona, it would be the 392nd BG and would consist of four squadrons: the 576th, 577th, 578th and 579th Bomb Squadrons. On completion of its training, the 392nd would leave the United States, and fly across the Atlantic to their new base in England. These four squadrons would be the first to operate the newly updated B-24 ‘H’ model ‘Liberators’; an improvement of the previous variants by the addition of a motorised front turret, improved waist gun positions and a new retractable belly turret. The supporting ground echelons had left the United States, sailing on the Queen Elizabeth from New York, much earlier, and before the group had received these newer models. As a result, they had neither received any training, or gained any experience with these new updated variants. The arrival of these new aircraft would therefore be met with some surprise, followed by a steep learning curve supported by additional training programmes.

The first B-24s of the 392nd arrived at Wendling, Norfolk, on 15th August 1943, and would soon be joined by the 44th at nearby Shipdham, the 389th at Hethel and the 93rd at Hardwick; four Groups that would be combined to form the Second Bombardment Wing (later 2nd Bombardment Division)*1. Battle hardened from fighting in the Mediterranean Theatre, these other three groups knew only too well the dangers of bombing missions, all having suffered some heavy losses themselves already.

During September 1943, the 392nd joined with these other three units flying missions under Operation ‘Starkey‘; probing German defences and gauging their responses to massed allied attacks on coastal regions. Largely uneventful they went on to undertake diversionary missions over the North Sea, the first three being escorted by fighters, and without incident. On the fourth however, the fighters were withheld and the bombers struck out alone.

On this particular flight, 4th October, 1943, the 392nd would gain their first real taste of war, and it would be an initiation they would rather forget. During the battle over thirty Luftwaffe fighters would shoot down four B-24s with the loss of forty-three crew members. A further eleven were injured in the remaining bombers that managed to continue flying and return home – it was not a good start for the 392nd.

Licking its wounds, they would then be combined with more experienced units, flying multiple missions as far as the Baltic regions before returning to diversionary raids again later that month. Viewed with some misgivings by crews, these ‘H’ model Liberators were soon found to be heavier, slower and less responsive at the higher altitudes these deeper missions were flown at.

The 392nd would take part in many of the Second World War’s fiercest operations; oil refineries at Gelsenkirchen, Osnabruck’s marshalling yards and factories at both Brunswick and Kassel were just some targets on the long list that entered the 392nd’s operations records book.

The massive effort of ‘Big Week’ of February 20 – 25th saw the 392nd in action over Gotha, in an operation that won them a DUC for their part. Upon entering enemy airspace, the formation was relentlessly attacked by Fw-190s, Me 110s and Ju 88s using a mix of gun, rockets, air-to-air bombing and even trailing bombs to disrupt and destroy the groups. Ironically it was the very same twin-engined aircraft and component factory that was the intended target that day; a focus of the Second Bomb Division in an operation that saw the lead section, headed by aircraft of the 2nd Combat Wing, bomb in error due to the bombardier collapsing onto his bomb release as a result of oxygen starvation. Unrelenting the 392nd carried on. They realised and ignored the major error, and flew on to drop 98% of their bombs within 2,000 feet of the intended target. This highly accurate bombing came at a high cost though, Missing Air Crew Reports (MACR) indicate seven aircraft were lost, with another thirteen sustaining battle damage.

The 392nd would carry on, with further battles taking their deadly toll on both crews and aircraft. In March that same year, the 392nd would turn their attention to Friedrichshafen – a target that would claim further lives and be the most costly yet.

Even before entering into enemy territory, losses would be incurred. Flying in close formation, two B-24s flew too close – one through the prop wash of another – which caused them to collide bringing both aircraft down. One of those B-24s #42-109824 ‘Late Date II‘, lost half of its crew.

Despite good weather over the target the attack on Friedrichshafen in southern Germany, would have to be led by pathfinders. In an attempt to foil the attackers, the Germans released enormous quantities of smoke, enveloping the town and concealing it from the prying eyes high above. Of the forty-three bombers to fall that day, half were from the 14th Combat Wing of which fourteen came from the 392nd. Despite losses elsewhere, this would prove to be the worst mission for the 392nd, in all some 150 crew men were lost that day.

Bombing targets in Europe was never straight forward and bombs often fell well away from the intended site. On one rather unfortunate occasion at the end of March, the 392nd joined the 44th BG in mistakenly bombing Schaffhausen, a town in neutral Switzerland. The event that not only deeply upset the Swiss, but heavily fed the Nazi’s determined propaganda machine.

Eventually March, and its terrible statistics, was behind them. The 392nd would then spend the reminder of 1944 supporting ground troops, bombing coastal defences in the lead up to D-day (their 100th mission), airfields and V-weapons sites in ‘NOBALL‘ operations. Like many of their counterparts they would support the St. Lo breakout, and hit transport and supply routes during the cold weeks of the Battle of the Bulge.

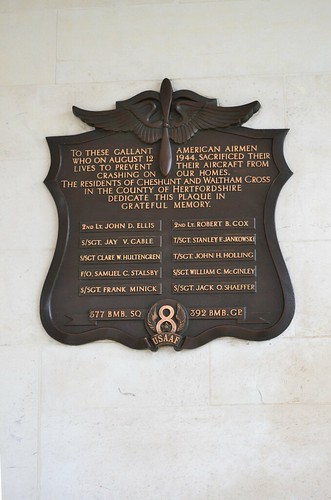

It was during this time, on 12th August 1944 that heroic pilot, 2nd Lt. John D. Ellis, flying B-24H #42-95023, would manage to steer his stricken aircraft away from a residential area at Cheshunt, some 15 miles north of London, crashing the aircraft near to what is now the A10 road. Sadly all on board were killed in the incident but undoubtedly the lives of many civilians were saved, and a memorial in their memory lies in the nearby library at Cheshunt and on the wall at Madingley, the American War Cemetery, Cambridge.

This was not to be the only accident that the 392nd (nor any other B-24 unit) were to suffer. Crews were finding that these heavier machines were difficult to get out of if hit by flak or attacking fighters. Ferocious fires in the wing tanks and fuselage were leading to many losses, and in particular, the pilots who after fighting to keep aircraft stable long enough for crewmen to jump out, were then finding it viciously spinning the moment they let go of the controls.

On February 16th 1945 Liberator #42-95031 ‘Mary Louise‘ flown by 1st Lt. Albert J. Novik, was hit by falling bombs from another aircraft flying above him. After wrestling for some four and half hours to keep the aircraft flying, he ordered the crew out and then attempted to leave the aircraft himself. This event occurred only a month after a similar incident where he had managed to dive through the open bomb bay to safety. In this instance though, Novik was pinned to the roof as the bomber, half its tail plane missing, spun violently towards the Norfolk landscape beneath. Eventually, after a 7,000 ft fall, he was released from this centrifugal grip by a change in the aircraft’s direction. He managed to crawl down from his position and throw himself out through the bomb bay just seconds before the aircraft exploded, sending burning aircraft parts tumbling all around him. For his actions Novik was awarded the DFC, but many others were not quite so lucky, and perished in these huge lumbering giants of the sky.

On April 25th 1945, Mission 285, the 392nd BG prepared for what would be their last mission of the war. The Target, Hallein Austria. Not only would it end the 392nd’s aerial campaign, but that of the Eighth Air Force, bringing the air war in Europe to an end for the American units based in England.

By then, the 392nd had conducted some 285 missions with a high rate of loss, some 184 aircraft in total, with over 800 young men killed in action. They had dropped around 17,500 tons of bombs on some of the highest prestige targets in the German heartland. The group was cited by Major General James Hodges for its degree of accuracy for bombs on target – higher than any other unit of the 2nd Air Division over 100 consecutive missions. Operations had ranged from Norway to southern France and as far as the Baltic and advancing Russian armies at Swinemunde. Over 9,000 decorations were handed out to both air and ground crews for bravery and dedication.

After flying food supply missions to the starving Dutch, the 392nd departed Wendling and the site closed down, remaining dormant until it’s disposal in 1963/4.

RAF Wendling, otherwise known as Beeston from the nearby village, was classified as Station 118 by the Americans. Initially intended as an RAF Bomber base it was updated during the winter of 1942/43 opening in the summer of 1943. It would have 3 concrete runways of class ‘A’ specification, one of 2000 yards and two of 1,400 yards. The bomb dump which survives today as a nature reserve, was to the south-east, whilst the technical area is to the north-west. Two T2 hangars were located near to these sites and the watch office (drawing 5852/41) seems to have been modified in 1943 with the addition of what may have been a Uni-Seco control room (1200/43). Originally built with an adjoining Nissen hut (operations / briefing room) this is now encompassed within another more modern building, and is not visible from the outside.

Around the perimeter were a mix of ‘pan’ (28) and ‘spectacle’ (26) style hardstands, all of which have since been removed or built upon. The technical area, housing a range of: stores, workshops, huts and associated buildings, were to the north-west also. Interestingly, Wendling used Orlit huts, built by the Orlit Company of West Drayton, a mix of panel and concrete posts they were more economical than the British Concrete Foundation (BCF) huts initially ordered by the Ministry of Works.

Today, parts of two of the main runways still survive, housing turkey farms these buildings synonymous with Norfolk. The third was removed and the perimeter track has been reduced to a path. The bomb dump is part of a local nature reserve which has very limited parking, but access to the remaining buildings there is straight forward. Many of the buildings from the remaining twelve accommodation sites have been removed, however a number are still believed to be standing bound in heavy undergrowth, or used by local businesses. One currently retains a huge mural covering an entire wall, with evidence of others also within the same building.

Unfortunately when I visited Wendling, daylight ran out forcing me to make a retreat and head for home – a return visit is certainly planned for later. Like many other airfields in this part of the country, losses were high, and the toll on human life dramatic, both here, ‘back home’ and of course, beneath the many thousands of tons of high explosives that were dropped over occupied Europe. Now a high number of these sites house turkey farms, small industrial units or have simply been dug up, and forgotten. I hope, that we never forget and that they all get the honour and respect they deserve.

On a last note, there is a remarkable memorial in the Village of Beeston to the west of the airfield site. This is in itself worth a visit. Not only does it mention the 392nd, but all the auxiliary units stationed on the base, something we often forget when considering the Second World War. A nice and moving end to the trip.

Sources and Further Reading (RAF Shipdham).

Lundy, W., “44th Bomb Group Roll of Honor and Casualties“, 2005, Greenharbor.com – a detailed account of the 44th’s missions, including personal accounts of each mission and details of the losses. (Twitter @44thbgROH)

Todd, C.T., “History of the 68th Bomb Squadron 44th Bomb Group – The Flying EIghtballs“. PDF document

Notes and further reading (RAF Wendling).

*1 September 1943 saw a reorganisation of the US Eighth Air Force, and in September, the ‘Wings’ designation was changed to ‘Divisions’. Then in early 1944, a further reorganisation led to further strategic changes of the Air Force, one of which, saw the 44th and 392nd join with the 492nd to form the 14th Combat Wing, 2nd Bomb Division. Both the 389th and the 93rd became part of the 2nd and 20th Combat Wings respectively.

A detailed website covering every mission, aircraft and most crew members offers a good deal of information and supporting photographs. It is well worth a visit for further more detailed information .