In this next trail, we start just a few miles to the south-west of Bury St. Edmunds in Suffolk, where we visit a number of airfields that were associated with the heavy bombers of the RAF’s Bomber Command.

Our first stop, although a satellite, more than earned its rightful place in the history books of aviation. It is an airfield where large numbers of the ill-fated Stirling flew many missions over occupied Europe, where the staggering statistics of lost men and machines speak for themselves.

Now little more than fields and a small industrial estate, the remnants of this wartime airfield stand as reminders of those dark days in the 1940s when night after night, young men flew enormous machines over enemy territory to drop their deadly payload on heavily defended industrial targets.

We begin our next trip at the former airfield RAF Chedburgh, home to the mighty four-engined bombers of No. 3 Group Bomber Command of the Royal Air Force.

RAF Chedburgh.

Built in 1942 (by John Laing and Son Ltd) as a satellite for RAF Stradishall, Chedburgh would be built to the Class A specification, a later addition to the RAF’s war effort. Being a bomber station Chedburgh would have three runways made of concrete, the initial construction being one of 2,000 yards and two of 1,400 yards, all the standard 50 yards wide, as was the standard specification brought in during 1941. Later on, these would be extended giving Chedburgh much longer runways than many of its counterparts, i.e. one at 3,000 yards and two at 2,000 yards. Having runways this long, meant that heavy bombers could use the site when in trouble, something that Chedburgh would get used to very quickly.

With the village of Chedburgh to the north of the site, directly opposite the main gate; the technical area along the north-eastern side of the main runway, and the bomb store to the east, Chedburgh would have two T2 hangars, a B1 and later on 3 glider hangars. Dotted around the perimeter track were a number of dispersals comprising 34 pan styles and 2 looped.

Whilst housing only two major squadrons 214 Squadron and 620 Squadron, it would also be home to a small number of other operational units, 218, 301, 304 Sqns and 1653 Heavy Conversion Unit (HCU).

Opening under the control of No. 3 Group, on September 7th 1942, the first resident unit was 214 Squadron (RAF) flying the Stirling MK. I, a model they operated until as late as February 1944. The bulk of the unit arrived in the October, with operations beginning very soon after. Within four months they would begin replacing some of these models with the upgraded MK.III, also operating these until the beginning of 1944 and after transferring to RAF Downham Market in Norfolk.

As with many airfields at this time, the arrival of personnel preceded the completion of the works, development continuing well into the operational time of its residents, something that would cause a problem in the coming months.

It was in March of 1943 that the first casualties would occur, the night of March 1st/2nd being a baptism of fire for 214 Sqn. Stirling MK. I (R9143) BU-E piloted by F/S. J. Lyall (RCAF) would be hit by flak, she was badly damaged, and then abandoned by her crew. As he descended from the stricken aircraft, F/O. Hotson (RNZAF) would be hit by a splintering shell – the wounding he received as a result would be fatal. The remainder of the crew all escaped the aircraft safely but were later captured by the Germans and incarcerated. A multi-national crew, this loss was to be followed just two nights later with the loss of another Stirling, ‘BU-C’, but this time none of the seven crewmen were to survive.

Then on the next night, 5th/6th March, whilst on operations to Essen (the 100,000th sortie by RAF aircraft), Stirling BK662 ‘BU-K’ crashed into the North Sea about 30 km north-northwest of Ijmuiden. Only one of the crew, Air Gunner Sgt. William H. Trotter (s/n: 1128255) was ever found, the rest of the crew remaining ‘missing in action’. This was the first Stirling to be listed as such since the squadron’s operations began. This raid would prove devastating, taking the lives of 75 RAF airmen, but the War Office considered it a major success in terms of industrial damage to the German war machine. The targeted Krupps factory, which sat in the centre of over 100 acres of industrialised area, was devastated by both accurate marking and then the subsequent bombing.

Throughout this month there were further loses to the squadron: Stirlings ‘BU-Q’ and ‘BU-A’ (in which F/S. D Moore (RCAF) and Sgt. T. Wilson were both awarded the George medal for saving the life of their companion Sgt. J. Flack), along with ‘BU-M’ were all lost; ‘BU-M’ losing all but one crewman. Another aircraft, ‘BU-L’, lost all seven aircrew on the night of March 27th/28th, and closing March off, was a collision between Stirlings BK663 and EF362, which left several more crewmen either injured or dead. Although many losses were as a direct result of flak or night fighters, the cracks were beginning to show, and the poor performance of the Stirling was becoming evermore apparent.

It was during this year on 17th June 1943, that Chedburgh’s second main operational unit would be formed, 620 Sqn (RAF), also carrying out bomber operations, again with the Stirling MK. I and later in the August, the MK. III. Also part of 3 Group Bomber Command, 620 Sqn were created through the streamlining of 214 Sqn and 149 Sqn at nearby Lakenheath. The move reduced each of the two former squadrons from three flights to two, releasing ‘C’ Flight of 214 Sqn who were already stationed here at Chedburgh.

As many of these crews were already well established and experienced, there would be no delay in commencing operations, the first sortie occurring on the night of the 19th June 1943 – two days after their formation. The first casualties occurred three days later on the night of 22nd/23rd June 1943, just a few days into their operational campaign. There then followed five months of heavy operational activity, a period in which the Stirling and its crews would be pushed to the very limit and beyond. The shortcomings of the aircraft being realised further more.

Being on a partially built airfield would be the cause of the demise of Stirling EF336 (QS-D) which swung on take off and ran into the partially constructed perimeter track. The uneven surface caused the undercarriage to collapse, and whilst there were no injuries to the crew, the aircraft was written off.

The poor service ceiling of the Stirling led to several aircraft being damaged through falling bombs from aircraft flying above. A number of Stirlings were recorded returning to bases, including Chedburgh, with damage to the air frames, damage caused by these falling ‘friendly’ bombs! However, the extent of this damage did give great credit to the aircraft, showing both its robustness and strength in design; something that often gets forgotten when talking about the Stirling in operations.

The next few months for 620 Sqn would be filled with a mix of operational sorties, mining operations (Gardening) and training flights, including both ‘Bullseye‘ and ‘Eric‘; testing the home defence searchlight and AA batteries both at night and during the day. During a fighter affiliation exercise on July 2nd, two 620 Squadron aircraft collided, ‘EF394’ (QS-V) and BK724 (QS-Y) killing fifteen and injuring two. One of those killed, Flight Mechanic AIC Arthur Haigh (s/n: 1768277) was only 18 years old, and one of five ground crew who were aboard the two aircraft that day.

Both 214 Sqn and 620 Sqn would go on for the next few months taking part in some of the war’s largest bomber missions including Hamburg, Essen and Remscheid. A number of aircraft would be lost and many aircrew along with them. The worst recorded night for 620 Sqn was the night operation on August 27th/28th, 1943 to Nuremberg, when three aircraft were shot down, all Stirling MK.IIIs: BF576 (QS-F) piloted by Sgt. Frank Eeles (s/n: 1531789); EE942 (QS-R) piloted by Flt. Sgt. John F. Nichols (s/n: 1318759) and EF451 (QS-D) piloted by Sgt. William H. Duroe (s/n: 658365). These three losses accounted for sixteen deaths and five taken as POWs, there were no other survivors.

The last 214 Sqn Stirling to be written off during bombing missions occurred on the night of November 22nd/23rd, 1943. Whilst on a mission to Berlin, Stirling EF445 (BU-J) was hit by flak, attacked by a FW-190 and then suffered icing. The resultant damage along with a lack of fuel, caused the pilot to ditch in the North Sea with the loss of two crewmen: pilot F/S. George A. Atkinson (s/n: 1485104) and Sgt. W. Sweeney (RCAF) (s/n: R/79844).

620’s stay at Chedburgh would be fairly short-lived, taking part in their final operation on the night of November 19th/20th, 1943 to Leverkusen. They then departed Chedburgh at the end of that month after suffering a heavy toll on their numbers and a devastating start to their war. By now the limitations of the Stirling were very well-known, and it was already being replaced by the much favoured Lancaster. In the short five months it had existed, the squadron had lost eighteen of its aircraft in operations, and a further six in accidents, statistics that are however, overshadowed by the loss of ninety-three lives. 620 Sqn left both Chedburgh and Bomber Command to join other units at RAF Leicester East and the Allied Expeditionary Air Force in November, where the unit was to perform Airborne operations along side 196 Sqn and 1665 Heavy Conversion Unit (HCU). A role that 620 performed for the remainder of the war.

With their departure came the arrival of another Stirling squadron, 1653 HCU, a Stirling training unit rather than a front line operational squadron. A month later 214 Sqn would also leave Chedburgh taking their Stirlings to Downham Market and then onto Sculthorpe where they replaced them with the B-17 Flying Fortress.

A P-51 Mustang (5Q-Q, serial number 42-106672) of the 504th Fighter Squadron, 339th Fighter Group, that has crash landed at Chedburgh, 18 May 1944. (IWM FRE 2784)

1653 HCU, as a training unit, would also have it share of accidents and losses, many due to technical problems, but some due to pilot error. A number of accidents were caused by tyres blowing, and some were caused by engine failures, the bravery of these pilots in dealing with these matters being no less than exemplary. One such incident being that of F/O. Hannah and his crew, who took off at 20:50 on the evening of November 3rd 1944, on a radar training flight. Immediately after take off both port engines cut out, something that was almost fatal in a Stirling. The aircraft, virtually uncontrollable, was heading towards a row of cottages but the crew managed to turn it away missing the houses but colliding with a row of trees instead. All of the crew were injured to varying degrees – one fatally. Sgt. Eddie (RCAF) dying in the resultant crash.

After a year of being at Chedburgh, 1653 HCU would also depart (December 1944) by which time the Lancaster was well and truly the main bomber of the RAF. This late stage of the war would not be the end of Chedburgh though, Bomber Command retaining its use, sending the Lancasters I and III of 218 (Gold Coast)*1 Squadron here from RAF Methwold.

On December 2nd 1944 the first ground units began to arrive, with flying personnel arriving on the 5th, after much-needed runway repairs were completed. The airfield reopened with the arrival of eighteen Lancasters, formed into three new flights, of which thirteen would undertake operations on the 8th, to the railway yards at Duisburg – their first from Chedburgh. Both this mission and that of the 11th to the marshalling yards at Osterfeld, were heavily restricted by thick cloud, and so G-H navigation aids were used in conjunction with ‘Oboe‘.

For the majority of the remainder of the war Bomber Command continued its strategic missions against German cities, with marshalling yards and oil refineries being other major targets. It was of course this continued use of bomber aircraft against what was now a demoralised and weakened German population, that led to the outcry over Harris’s continued attacks on German cities. A controversial action that led to his move away from the lime light at the war’s end, and the lack of recognition for bomber commands efforts throughout the conflict.

218 Sqn would continue on though. The winter of 1944 / 45 proving to be one of the worst weather wise, many missions were either scrubbed or carried out in poor weather. On the night of January 1st/2nd 1945, one hundred and forty-six aircraft of No. 3 Group were tasked with the attack on Vohwinkel railway yards. During the attack in which 218 Sqn were a part, two aircraft were hit by heavy anti-aircraft fire from American guns below. One of these was 218 Sqn Lancaster MK. I PB768 (XH-B) piloted by 20 yr old Australian F/O. Robert G. Grivell. The accuracy of these guns was ironically excellent, hitting the aircraft not once but twice, causing it to spin uncontrollably toward the ground. All but one of the crew were killed in the ensuing crash.

It was during this period that the RAF began daylight bombing missions too, such was the poor state of the defending Luftwaffe. Numerous missions over the next weeks led to attacks on the coking plants at both Datteln and Hattingen, repeated again on March 17th in attacks at Huls (and Dortmund). Hattingen was again attacked by 218 Sqn aircraft on the 18th without loss.

Mechanics at work on an engine of Lancaster B Mk. III, (LM577) ‘HA-Q’ “Edith”, of No. 218 Squadron. On March 19th 1945, this aircraft was hit by flak over Gelsenkirchen damaging the rear turret and injuring the gunner’s eye. LM577 went on to complete more flying hours than any other Lancaster on the station. (@ IWM CH 15460)

The remainder of the war would see 218 Sqn fly from Chedburgh, completing many missions until the war’s end. During Operation ‘Manna‘ in which the German Army lifted an embargo on food transport into Holland, ten Lancasters of 218 Squadron dropped food supplies to the starving Dutch below. Understandably April had seen fewer operations than in previous months, but with May seeing many more food trips to the Hague, 218 Squadron leapt to the top of the leader board for operational tours, overtaking both 77 Sqn and 115 Sqn their closest friendly ‘competitors’. With further flights under ‘Manna‘, and then repatriation flights under both ‘Dodge‘ and ‘Exodus‘ 218 Sqn continued to operate the long haul flights into European territory.

During August the big wind down began, and the Lancasters were gradually flown out of Chedburgh for disposal. Then on the 10th, 218 (Gold Coast) Squadron was finally disbanded, and the various crews sent home to their respective territories across the globe.

On August 27th 1945, the last two Lancasters departed Chedburgh, and all was very quiet for those left behind. Then in September, two Polish bomber squadrons arrived, both 301 and 304 Sqns remaining here until they were also disbanded a year later on December 18th, 1946; their Warwicks, Wellingtons and Halifaxes being no doubt scrapped. Whilst here, the Polish squadrons flew long-range transport flights, retaining at least some link to the heavy aircraft and long-range flights that had been common only a year or so before.

Over the remaining years the airfield, like many, has reduced to both agriculture and industrial use. The watch Office has been heavily modified and lies hidden within an industrial complex that has completely taken over the former technical site. A number of these original buildings still survive and visible from the main A143 Bury St. Edmunds to Haverhill road, the road that separates the airfield from the village opposite. The runways and perimeter tracks, visible only in small parts, are mere concrete platforms, now used to store farm produce and machinery, rather than the lumbering bombers of RAF Bomber Command.

The huts used to house the 1,600 RAF personnel and 240 WAAFs, have all been removed, as have the thirty-six hardstands – the airfield site now being completely agricultural.

Whilst Chedburgh was only built as a satellite airfield, by the end of the war it had been witness to many great sacrifices. Eighty-three aircraft had been lost on operations, all but 12 being Stirlings; eighteen from 620 Sqn and fifty from 214 Sqn. For a period of only fourteen months for 214 Sqn and five for 620 Sqn, this was an appalling loss of life, and one that was sadly mirrored by many bomber squadrons across the British Isles in the 1940s.

Moving on from RAF Chedburgh, we continue south-west along the A143 to another former bomber airfield, and the parent station of Chedburgh. This next site has a history that dates back to the late 1930s and is one that has many of its original buildings still in situ, many thankfully still being used albeit by a completely different organisation.

The next stop on this trail is the historically famous airfield the former RAF Stradishall.

RAF Stradishall.

RAF Stradishall has a rather unique history, it was one of the first to be built during the expansion period of Britain’s Air Force beginning in 1935. A series of Schemes, this programme was to develop the RAF over a period of years to prepare it for the forth coming war; a series of schemes that continued well into the war and created the basis of what we see today around Britain’s forgotten landscape.

This first scheme, Scheme ‘A’ (adopted by the Government in July 1934), set the bench mark by which all future schemes would develop, and called for a front line total of 1,544 aircraft within the following five years. Of these aircraft, 1,252 would be allocated specifically for ‘home defence’. This scheme brought military aviation back to the north of England, and to the eastern counties of Norfolk and Suffolk. Under this scheme, a number of airfields would be built or developed, of which Marham (the first completed under these schemes), Feltwell and Stradishall were among the first. These airfields were designed as “non-dispersed” airfields, where all domestic sites were located close to the main airfield site, and not spread about the surrounding area as was common practice in later airfield designs. At this stage, the dangers of an air attack were not being whole heartedly considered, and such an attack could have proven devastating if bombs had been accurately dropped.

Thus in 1938 Stradishall was born, its neo-Georgian style buildings built-in line with common agreements and local features. Within the grounds of the airfield accommodation blocks provided rooms for just over 2,500 personnel of mixed rank, and all tightly packed in within the main airfield site.

In these pre-war years, the development of hard runways and large airfields was a new phenomena, hard surfaces being a new aspect still very much a topic of considerable controversy. By now, Bomber Command had realised that the new era of bombers would call for hard runways on its airfields, and so they pushed the Government on allowing these to be developed. However, before any firm decisions could be made, trials would need to be carried out to determine whether or not they were indeed needed and if so, how they should be best constructed.

The test to determine these needs was to take a Whitley bomber, laden to equal its full operational weight, and taxi it across a grassed surface. A rather primitive assessment, it was intended to ascertain the effects of the aircraft on the ground beneath. Trials were first carried out at Farnborough and then Odiham, and these were generally successful, the Whitley only bogging down on recently disturbed soils. Further trials were then carried out here at Stradishall in March 1938, and the results were a little more mixed. Whilst no take offs or landings took place during these trials, the general agreement was that more powerful bombers would have no problems using grassed surfaces, as long as the ground was properly prepared and well maintained. All well and good when the soils were dry and well-drained.

However, Dowding continued to press home the need for hard surfaces, and by April 1939, it had finally been recognised by the Air Ministry that Dowding was indeed right. A number of fighter and bomber airfields were then designated to have hard runways, of which Stradishall was one. These initial runways were only 800 yards long and 50 yards wide, extended later that year to 1,000 yards long, as aircraft were repeatedly running off the ends of the runways on to the grassed areas. Over the years Stradishall would be expanded and further developed, its longest runway eventually extending to 2,000 yards.

Stradishall was also one of the first batch of airfields to have provisions for the new idea of dispersing aircraft around the perimeter. To meet this requirement, hard stands were created to take parked aircraft between sorties, thus avoiding the pre-war practice of collective storage, and so reducing the risk of damage should an attacking force arrive – a practice not necessarily extended to the accommodation! By the end of development, Stradishall would have a total of 36 hardstands of mixed types, the extension of the runway being responsible for the removal and subsequent replacement of some. For maintenance, five ‘C’ type hangars and three ‘T2’ hangars were built, again standard designs that would be later superseded as the need required.

As Stradishall was one of this first batch of new airfields, it would also be used for trials of airfield camouflaging, particularly as the now large concrete expanses would reveal the tell-tale sign of a military airfield. On wet days the sun would shine off these surfaces making the site highly visible for some considerable distance. Initial steps at Stradishall used fine coloured slag chippings added to the surface of the paved areas. Whilst generally successful, and initially adopted at many bomber stations, Fighter Command refused the idea as too many aircraft were suffering burst or damaged tyres as a result of the sharp stones being used. Something that is reflected in many casualty records of airfields around the country.

The Type ‘B’ Officers Mess at Stradishall is now a Prison Officers Training Facility. The Officers quarters are located in wings on either side of the mess hall.

On opening Stradishall would fall under the command of 3 Group Bomber Command, and would operate as an RAF airfield until as late as 1970, being home to 27 different operational front line squadrons during this time. Many of these would be formed here and many, particularly those post-war, would be disbanded here, giving Stradishall a long and diverse history.

The first squadrons to arrive did so on March 10th 1938. No. 9 Sqn and No. 148 Sqn (RAF) arriving with Heyford III and the Vickers Wellesley respectively. 148 Sqn replaced these outdated Wellesleys with the Heyfords in November, and then again replacing these with both the Wellington and Anson before departing for Harwell on September 6th 1939. No. 9 Sqn also replaced their aircraft with Wellingtons in January 1939, themselves departing on July 7th that same year.

It was during a night training flight, on November 14th 1938, that Wing Commander Harry A. Smith MC along with his navigator Pilot Officer Aubrey W. Jackson would be killed in Heyford III K5194, when the aircraft undershot the airfield striking trees outside the airfield boundary. The crash was so forceful that the aircraft burst into flames killing both airmen.

Wing Commander Smith MC qualified as a pilot whilst in the Royal Flying Corps in 1916, and was the first of his rank to be killed since the inception of Bomber Command in July 1936. He had been awarded the Military Cross ‘for gallantry and distinguished service in the field‘ in 1918.

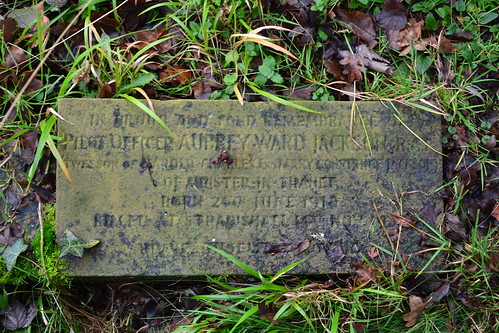

Pilot Officer Jackson was appointed for a Short Service Commission in January 1937, and later a Permanent Commission. He was only 20 years old at the time of his death.

Both crewmen are buried in Stradishall’s local cemetery.

A very much less than grand grave stone marks the plot of P.O. Aubrey W. Jackson, killed on November 14th 1938 on a night training flight.

Wing Commander Smith, killed alongside P.O. Jackson on a night training flight. He was the first of his rank to die since the formation of Bomber Command.

Two more squadrons arrived here in 1939. No. 75 Sqn operated the Wellington MK. I from July, departing here just after the outbreak of war in September, and 236 Sqn flying Blenheims between the end of October and December that same year. 236 Sqn were reformed here after being disbanded in 1919, and after replacing the Night-Fighter Blenheims with Beaufighters, they went on with the type until the end of the war and disbandment once more. Almost simultaneously, 254 Squadron reformed here in October 1939, also with Blenheims. They remained here building up to strength before moving to RAF Sutton Bridge in Lincolnshire in December – one of many ‘short stay’ units to operate from Stradishall during its life.

This pattern would set the general precedence for the coming years, with bizarrely, 1940 seeing what must have been one of the shortest lived squadrons of the war. No. 148 Sqn being reformed on April 30th with Wellingtons only to be disbanded some twenty days later!

This year saw three further squadrons arrive at Stradishall: 150 Sqn on June 15th, with the Fairy Battle (the only single engined front line aircraft to be used here during the war), whilst on their way to RAF Newton; a detachment of Wellington MK.IC from 311 Sqn based at East Wretham (Sept); and 214 Sqn flying three variants of Wellington between 14th February 1940 and 28th April 1942. No. 214 Sqn would be the main unit to operate from here during this part of the war, and would suffer a high number of casualties whilst here.

On June 6th 1940, 214 Sqn Wellington IA ‘N2993’ piloted by F/O. John F. Nicholson (s/n 70501), would take off on a routine night flying practice flight. During the flight, it is thought that F/O. Nicholson became blinded by searchlights throwing the aircraft out of control. Unable to regain that control, the aircraft came down near to Ely, Cambridgeshire, killing the five crewmen along with an additional Leading Aircraftman (LAC) Maurice Peling who had joined them for the flight. A tragic accident that needlessly took the lives of many young men. F/O. Nicholson is buried in the local cemetery at Stradishall, whilst the remainder of the crew are buried in different cemeteries scattered around the country.

214 Sqn began operations from Stradishall on the night of June 14th/15th, the day German forces began entering Paris. This first raid was to the Black Forest region of Germany, a mission that was relatively uneventful.

Joining 214 Sqn at Stradishall was another unit, 138 Sqn*1 between December 1941 and March 1942. Flying a mix of aircraft, including the Lysander, Whitley, and later: Liberator, Stirling and Halifax, they would perform duties associated with the Special Operations Executive (SOE) carrying out clandestine missions dropping agents behind enemy lines.

It was one of these aircraft, Lysander III T1508, that crashed in January, nosing over near to the French town of Issoudun, a medieval town that bordered the regions of occupied France and ‘free’ France. The towns people protected many wanted resistance supporters, and so it was the scene of many heroic acts. From this particular accident, Squadron Leader J. Nesbit-Dufort managed to escape, evading capture and eventually returning to England where he was awarded the DSO for his actions. Needing to destroy the aircraft, locals pushed the Lysander onto nearby railway lines where it was obliterated after being hit by a passing train*2. It is believed that this was the first Lysander to be lost on these clandestine operations.

This night of January 28th/29th 1942, was a particularly bad night for Stradishall, with three aircraft being lost, two from 138 Squadron and one from 214 Squadron. Thirteen souls were lost that night none of which have any known grave.

1942 would also see a short one month stay by the Wellingtons of 101 Squadron, a detachment of 109 Squadron, and the accommodation of 215 Squadron’s ground echelon. Formed at Newmarket, the ground crews were posted to India whilst the air echelons were formed up at Waterbeach joining them with Wellingtons in April.

An updating of Wellington MK.Is with the MK.VI saw the remainder of 109 Squadron move into Stradishall, only leaving a small detachment at Upper Heyford – a residency that only lasted 4 months between April and July 1942. As 109 Sqn left, Stradishall was joined by the Heavy Conversion Unit 1657 HCU.

Formed as a bomber training unit through the merger of No. 7, 101, 149 and 218 Squadron Conversion Flights and 1427 (Training Flight), it would also operate the Stirling, and later the Lancaster along with some smaller aircraft such as the Airspeed Oxford. They would remain here until late 1944 when they too were finally disbanded. This meant that 1943 was quieter than usual, there wasn’t any sign of the previous ebbing and flowing that had taken place in the preceding years.

With a focus on training, few of these aircraft were used for ‘operational’ sorties until the closing stages of the war. That said, there were still a number of accidents and crashes that resulted in injury. A number of these were due to technical issues, engine failure, engine fires or undercarriage problems, some were due to pilot error. One of the earliest incidents here was that of Stirling MK.I W7470 which crashed, after suffering engine problems over County Durham. The accident killed two crewmen and injured a further two.

After a short spell at Honnington, 214 Sqn would join 1657 HCU, also replacing the Wellington with the ill-fated Short Stirling MK.I in April 1942. But the last flights of the Wellington would not be a good one. The night of April 1st/2nd 1942 would go down as 214 Sqn’s worst on record, and one that would prove devastating to the crews left behind.

The raid would be to Hanau railways yards located 25 km east of Frankfurt am Main. During the raid thirty-five Wellingtons and fourteen Hampdens from both 57 Squadron (RAF Feltwell) and 214 Sqn (RAF Stradishall) would be dispatched. Take off was between 20:00 and 21:00 hrs and the attack by 214 Sqn would be carried out at heights as low as 400 feet using a mix of 250 lb and 500 lb bombs with impact fuses and some 3 hour delay fuses. During the attack, railway lines, bridges and carriages were hit, explosions were seen and the gunners strafed stationary trains and gun positions. The bomb aiming and shooting was reported as ‘good’.*3

However, of the fourteen 214 Sqn Wellingtons that left, seven were lost and a further Wellington was hit in both engines by light flak the pilot nursing it back to England. Of those seven lost, one airman, Sgt. C. Davidson was taken prisoner of war, four have no known grave and the remaining thirty-seven all died, and remain buried in graves across Belgium and Germany. Truly a terrible night for 214 Sqn. 57 Squadron fared little better, losing five aircraft with the deaths of twenty-five airmen, the remaining five being taken prisoner.

Further losses that month were restricted to just odd aircraft with the last loss being recorded on the night of 28th/29th April, with all crewmen being lost. Before the month would be out, 214 would begin the conversion to Stirlings, a new start and a new challenge.

The Stirling would prove to be a robust but under performing aircraft, its short wingspan and subsequent lack of lift, proving to be its biggest downfall. 214 Sqn would, during the conversion programme, write off nine aircraft, much of this though being as a result of operational activity, some however, due to pilot error or accidents. The first incident occurring on May 5th, 1942, approximately one week into the programme, when Stirling N6092 piloted by F/O. Gasper and Sgt. M Savage, swung on take off resulting in its undercarriage collapsing.

In the October 1942, 214 Sqn would leave for the final time, moving off to Stradishall’s satellite airfield, RAF Chedburgh, where they remained until December 1943. Following this they transferred to RAF Downham Market. The last loss of a 214 aircraft at Stradishall being on the night of September 19th/20th with the loss of Stirling ‘BU-U’ R9356 along with four of the seven crew, the remaining three being taken prisoners. By the end of 1942, 214 Sqn would have lost thirty-three Stirlings, twice that of the Wellington, all-in-all a huge loss of life.

Former Married quarters are now private dwellings, but still retain that feel they had when they were first built.

The December of 1944 not only saw the departure, for the last time, of the Stirling as a heavy bomber, but it heralded the arrival of the Lancaster, the remarkable four-engined bomber that became the backbone of Bomber Command. In total 7,377 of the bombers were produced, including 430 that were constructed in Canada. A remarkable aircraft born out of the much under-powered and disliked Avro Manchester, it went on to fly over 156,000 sorties, dropping over 50 million incendiary bombs and over 608,000 tons of HE bombs.

186 Sqn would be the first unit here with the Lancaster both the MK.I and the MK.III, operating them in a number of missions over occupied Europe.

One of the saddest ends to the war and the operations of 186 Squadron was on the night of April 134th/14th. Whilst returning from bombing the U-boat yards at Kiel, two Lancasters: P8483 ‘X’ and P8488 ‘J’ collided at 02:26. Five of the crew from AP-X were killed, either instantly or as a result of injuries sustained, whilst all seven of AP-J lost their lives. This loss would account for a high proportion of the squadron’s losses, 186 Sqn only losing nine Lancasters in the six months of residency – a considerable change to the carnage suffered at Stradishall earlier on in the war. 186 Sqn would finally be disbanded here in July 1945.

Over the next four years, there would be a return of both the Stirling and the Lancaster, but this time in the transport role, as Stradishall was passed over to Transport Command. No. 51 Sqn, and No. 158 Sqn both flying Stirlings (158 Sqn being disbanded at Stradishall) 35 Sqn, 115 Sqn, 149 Sqn and 207 Sqn all operating various models of the Lancaster until February 1949.

There would then be a lull in operations at Stradishall between April and July 1949 whilst the airfield was put into care and maintenance. Following this 203 Advanced Flying School (AFS) moved in with a range of aircraft types, including the Meteor and the Vampire. Also thrown into the mix were a number of piston engined aircraft, notably the Spitfire XIV, XVI and XVIII, along with Tempests, Beaufighters and Mosquito T3s. Other training aircraft also came along covering everything from the Tiger Moth to the modern jet fighter. A new age was dawning.

On the night of August 31st and September 1st 1949, 203 AFS and 226 Operational Conversion Unit (OCU) at Driffield, would both disband and reopen under each other’s titles, the new 226 OCU now operating as the training unit converting pilots to jet aircraft.

To the left was the main airfield now covered by a solar farm, to the right would have been the hangars, the original apron concrete still visible.

The post war years of the 1950s would see Stradishall thrown back into front line operations once more, this time there would be no heavy bombers though, but there would be plenty of front line fighters.

First along were the night fighter variants of the Meteor (NF.11) and Venom (NF.3) between March 1955 and March 1957, a residency for a reformed 125 Squadron that coincided with 245 Squadron only 3 months behind them. No. 245 swapping the Meteor for the Hunter before being disbanded in June that year.

No. 89 Squadron (another unit reformed in December 1955) saw the arrival of the new delta wing Javelins FAW6 & FAW2 working alongside the ageing Venom Night Fighters. They flew these aircraft for thirteen months before being disbanded once more, and then renamed as 85 Squadron whilst here at Stradishall. After this re-branding they continued to fly the Javelins. In 1959 they too departed Stradishall for RAF West Malling and then onto RAF West Raynham, where they too disbanded once more.

1957 saw more of the same, 152 Squadron yo-yoing between Stradishall and Wattisham, finally disbanding here in July 1958 with 263 Squadron following a similar pattern, also disbanding here in the same month with their Hunter F.6s.

In July 1958, No. 1 Squadron were yet another unit to reform here, carrying on from where 263 Sqn left off. After replacing the F.6s of 263 Sqn with FGA.9s in the fighter / strike role, they finally departed to Waterbeach, eventually becoming a front line Harrier unit at Cottesmore.

Gradually operations at Stradishall were beginning to wind down. In June 1959 No. 54 Squadron also replaced the Hunter F.6s with FGA.9s before they too departed for Waterbeach in Cambridgeshire. 54 Sqn went on to fly both the Phantom and the Jaguar as front line operational units, all iconic aircraft of the Cold War. A very short spell by three Hunter squadrons led to the eventual closure of Stradishall in 1960 as a front line fighter station; 208, 111 and 43 Sqns all playing a minor part in the final operations at this famous airfield. The last flying unit No.1 Air Navigation School (ANS) finally closing the station doors as they too disbanded on August 26th 1970, being absorbed by No. 6 Flying Training School.

A considerable number of non-operational units would also operate from Stradishall throughout its operational life such as 21 Blind Approach Training Flight, meaning just short of 50 flying units would use the facilities at Stradishall, all helping to train and prepare aircrews for the RAF and the defence of Britain.

Stradishall’s long and distinguished aviation history finally came to a close when it was sold off and handed over to HM Prison Service, becoming as it is today, HMP Highpoint Prison (North) and HMP Highpoint Prison (South). A rather ungainly ending to a remarkably historic airfield.

Stradishall is located a few miles south-west of Chedburgh, the main A143 dissects the two prison blocks, the north side being the former accommodation area, with the south block being the technical area and main airfield site. Access to the site is therefore limited, however, the former officers mess and associated buildings are available to view, as are a number of former technical buildings. A large memorial is currently displayed outside the officer’s mess building, named Stirling House in memory of the aircraft type that flew from here, and it is open to the public. The foyer of the building, now a Prison Officer Training facility, is opened, and holds a roll of Honour, for those lost at the airfield.

The current Prison Officers Training facility is named after the ill-fated Stirling that flew from RAF Stradishall. The Memorial being well sign posted.

Through the high security fencing, and around the site a number of buildings can still be seen, the familiar layout and design being standard of wartime and post war airfields. By turning off the A143 prior to reaching the memorial site, a small back access road allows public access to the airfield site. This is now, in part, a conservation area where the runways have all been removed, parts of the perimeter track do still remain and public access is permitted. The runways have been replaced by a solar farm, large panels cover the entire area and all are encased in high security fencing with closed circuit TV preventing you from wandering too close to the high-tech plant.

Walking along the northern side of the airfield, views can be seen of the accommodation area, again a number of former buildings can be seen through the fencing, their style typical of the expansion period design.

The dilapidated gateway hides many original buildings and a layout that reflects airfield design of the expansion period.

Back on the main road, turning left passing the prison, a turn off gives access to the aforementioned officers mess and memorial, it is well signposted, and continuing on, brings you to the former married quarters, now private housing, again typical of airfield design. Across the road from here, a farm track still has a small number of buildings now in a very poor state, this would have been an entrance to the accommodation area behind the current north side Prison. They are both quite well hidden by undergrowth but they are visible with a little effort.

Stradishall, like many of the early expansion period airfields, with its neo-Georgian style architecture and well designed layout, lasted well into the cold war period. These early examples which set the standard for future designs, proved to be long-lasting and robust, unlike many of their later counterparts hastily built with temporary accommodation. Whilst a rather unfitting end to a long and distinguished life, the transformation into a prison has in part, been its saviour, and one that has preserved many of its fine buildings for the foreseeable future at least.

From here, we continue our journey toward Haverhill, turning north-west toward our next stop, the former RAF airfield Wratting Common.

Sources and further reading (RAF Chedburgh).

Much of the specific detail for these loses came from the Chorley, W.R., “Bomber Command Losses series”, published by Midland Counties Publications.

*1 A number of books are available on this squadron. One written by Ron Warburton, ‘Ron’s War‘ chronicles the life of a Flight Engineer of a Lancaster in 218 (Gold Coast) Sqn whilst at Chedburgh in 1945. It is published by RW Press, and available online. ISBN-13: 978-0983178804

A second book is also available, “From St Vith to Victory: 218 (Gold Coast) Squadron and the Campaign Against Nazi Germany“, written by Stephen Smith, and published by Pen and Sword Aviation in 2010 (ISBN10 1473855403). It details the life of 218 (Gold Coast Sqn) from its inception through to its disbandment in 1945.

A blog has also been set up dedicated to those who served in 218 (Gold Coast) Sqn and it gives a detailed history from 1936-1945. It has also been created by Stephen Smith who has also published other books relating to 218 Sqn including “A Short War” and “A Stirling Effort” which relates specifically to their time at RAF Downham Market. https://218squadron.wordpress.com/

Sources and Further reading (RAF Stradishall).

*1 419 (Special Duties) Flight were initially formed at North Weald on 21st August 1940, being disbanded and re designated 1419 (Special Duties ) Flight on 1st March 1941 at Stradishall. They in turn were disbanded on 25th August 1941 to be reformed at Newmarket as 138 Sqn. they moved back to Stradishall on 16th December 1941. In February 1942, the nucleus of 138 Sqn formed 161 Sqn at Newmarket continuing the role of SOE operations from there.

*2 Grehan, J., Mace, M., “Unearthing Churchill’s Secret Army: The Official List of SOE Casualties and Their Stories“, Pen and Sword Military, 2012

*3 ORB 214 Sqn: AIR\27\1321\8 National Archives.