In Part one, we saw Tuddenham’s opening to the war. A rather cold and uninspiring airfield, it housed the Stirlings of 90 Squadron. Now, the Lancasters were arriving and front line bombing missions were once again on the horizon.

The first of these major operations was on the night of 10th/11th June, when seven Lancasters, a mix of MK.Is and MK.IIIs, left Tuddenham to bomb rail facilities at Dreux – 90 Sqn had at last returned to the ‘front line.’

Sadly it was not to be the best night for the squadron, of the seven Lancasters that departed, two never returned home. The first NE149 ‘WP-A’ and the second NE177 ‘WP-B’ (both MK.IIIs), crashing in France. Of the fourteen airmen on board, three evaded capture, one was caught, and the remaining ten were all killed – it was not the most auspicious start for the unit.

With two more Lancasters lost that month – one on the infamous Gelsenkirchen raid in which seventeen Lancasters were lost – June had proven to be difficult, and even though Stirlings were still operating, the Lancaster had become the main type and it wasn’t going to be an easy ride to Christmas. Forty-three, 90 Sqn airmen had been posted as either ‘killed’ or ‘missing’ in June alone.

Bomber Command’s tactical support of the land based forces continued on until mid September, by which time, Harris was back in charge and Bomber Command could once again turn its attention to targets in the German heartland. As the allied forces moved ever closer, night raids turned to daylight as allied air power began to get its grip on the skies over Europe.

In October, a new squadron would reform here at Tuddenham, 186 Squadron also flying Lancaster MK.I and IIIs. Originally having its roots on board HMS Argus in 1918, it was another unit that had had short spells of activity before being disbanded once again. In a very different guise to its original formation, this time it was born out of 90 Sqn’s ‘C’ Flight, there the differences cease and by the December, the squadron had left Tuddenham moving to Stradishall where it remained until the war’s end, and its final disbandment once more.

The remainder of the year was relatively quiet for the Tuddenham group, regular missions with little or no opposition meant losses were low, and results were generally considered successful. But with bad weather setting in across both the UK and the wider continent, many squadrons had days of being stood down. Tuddenham on the other hand, with their FIDO system, was able to put up more flights than many others. Indeed during the Battle of the Bulge in the Ardennes, 90 Sqn were one of the few units able to launch attacks when most others were fog bound.

The dawn of 1945 brought hope for an end to the war as the allied war machine moved ever closer to Berlin. The German’s last ditch attempt in the Ardennes was eventually overrun, and bombing picked up as fair weather returned once more.

On February 2nd, Wing Commander W. G. Bannister joined the squadron on attachment. On the same day as he arrived, he took off at 20:52 in Lancaster HK610 ‘WP-Z’ along with thirteen other Lancasters from the squadron. Around an hour later, the aircraft collided with Lancaster PD336 ‘WP-P’, striking the tail trapping the rear gunner, Sgt. K. Hudspeth, inside the turret by his legs. Injured, he lay slumped over his guns. The pilot turned the aircraft over the Wash and ordered the bombs dumped in the sea. The rear tyre of the aircraft was burst and the port side of the tail was badly damaged, maybe even missing, and the turret by now was hanging off the aircraft. The pilot ordered chutes to be put on, after which the mid gunner Sgt. G. Wraith, went to help Sgt. Hudspeth, pulling him back into the aircraft’s fuselage where he administered morphine. The Lancaster made its way back to Tuddenham, and with the radio knocked out, red flares were fired to inform ground staff of its difficulties. Badly damaged with injured on board, the Lancaster made a safe landing, thanks to the skill of the pilot and crew.

Bannister’s Lancaster however, did not recover from the collision. After striking ‘P’ for Peter, the aircraft fell from the sky, crashing at 21:25, 3 miles from Bury St. Edmunds; sadly there were no survivors.

March 1945 saw a return of the Stirling to Tuddenham with 138 Sqn*3 transferring from Tempsford with the MK.V. As soon as they arrived they began to replace these with Lancasters MK.I and IIIs. 138 Sqn had been heavily involved in clandestine operations with the SOE, dropping agents into occupied Europe. With the need for such missions now largely gone, operations were wound down and the Stirling squadron were to be upgraded to front line bomber status. The first operational mission under this new guise was planned for the 28th but postponed until the following day. Three aircraft were ordered and all returned safely after having bombed the target.

As the war drew to its conclusion, 90 Squadron turned their attention to Kiel with both mining and bombing to prevent a German withdrawal. By the of the month it was all but over and operation Manna was put into place. On April 30th, 90 Sqn began their part in dropping supplies to the Dutch – targeting Rotterdam. Drop zones were identified by red T.Is and / or white crosses placed on the ground. By the end of the month 23 tons of food supplies had been dropped by the one squadron alone. During May, they began flights to Juvincourt to collect and bring back prisoners of war, dropping them at various sites including Dunsfold, Tangmere, Wing and Oakley; the aircraft then returned to base before carrying out further flights.

On the 25th, ‘Cooks tours’ began, aircrew flying ground crew to Germany to see for themselves the damage inflicted by the war on the German heartland, it was a harrowing site for many.

With no operational flying to do, training flights took over. It was a major change for both the air and ground crews. As bases around the country began to close, so squadrons were moved around in preparation for disbandment. In April, two more Lancaster squadrons arrived here at Tuddenham, both 149 and 207 Sqns transferring across from RAF Methwold. The number of bomber squadrons now residing at Tuddenham totalling four.

Finally, in November 1946 the death knell finally rang for Tuddenham and it too was closed, flying ceased and the aircraft were all withdrawn. All four squadrons were pulled out of Tuddenham, 90 and 186 Sqns taking their Lancasters to RAF Wyton, whilst 149 and 207 went to RAF Stradishall. In what must have been a mass exodus, Tuddenham fell suddenly silent.

The airfield stood dormant for many years whilst remaining in RAF hands, but then in 1953 life returned once more as the USAF arrived and used it as an ammunition storage area and renovation depot for surplus WWII ammunition and equipment. The American forces remained here for four years until 1957 when they too finally withdrew.

Tuddenham itself continued to stay in RAF ownership for a short while longer. As tension rose in the early part of the Cold War, ideal because of its low population and rural location, it was earmarked as a site for the new Thor missiles. New launch pads were built and a small section of the site was redeveloped accordingly. Then in July 1959, 107 Squadron RAF reformed here, operating three of the Thor missiles as part of the UK-USA nuclear deterrent agreement. Retaining these until July 1963, the site finally closed once and for all. At this point all military personnel moved out and the gates were finally locked.

After this, Tuddenham was earmarked for quarrying to meet the rising demand for housing. Large sections were returned to agriculture, but a quarry opened to extract the much-needed materials for house construction. This operation has continued to the present day and has been responsible for the removal of large quantities of the main airfield site.

Visiting Tuddenham, reveals little of the history of the airfield and the people who stayed here. A few buildings, primarily the gymnasium and squash court remain standing, but in a very poor state and are likely to be pulled down soon. The roof has collapsed and part of the walls are missing. Located to the south of the airfield, they stand as reminders of those days long gone.

Other technical areas and the main part of the airfield, are now the workings of the quarry. The entrance to this site, rather insignificant, is part of the original perimeter track and is marked by an electrical sub-station. The shell is intact and complete with two blast walls, even the original RAF paint work can be seen! Overgrown and hidden beneath large thorns, this lone building will no doubt soon go the way of others some distance away.

Tuddenham airfield now stands lonely, large parts excavated and gone along with the memories of those who were stationed here. A pig farm covers a large part of the southern section and very little remains other than a few dilapidated buildings whose days are also very numbered. Tuddenham’s place in history is most certainly confined to the books and the memories of those whose numbers are also rapidly diminishing.

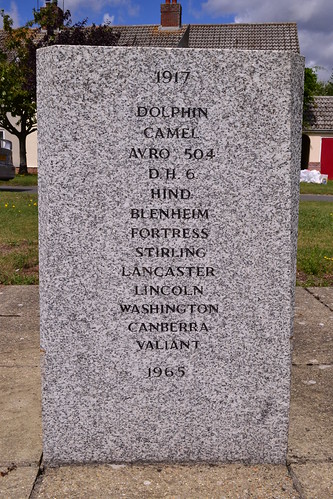

Before leaving Tuddenham, return to the village and stop at the village green. The village sign depicts a Lancaster flying low over the Suffolk landscape. A sundial, beautifully crafted marks the history of 90 Sqn, both the aircraft flown (1917 – 1965) as well as the airfields they were stationed at throughout their life. A superb tribute to a once active airfield and the gallant heroes of 90 Squadron Royal Air Force who served here*4.

In July 2021 I was contacted by Herb Zydney who was stationed at the former RAF Tuddenham in the mid 1950s, he kindly sent some photos and has since sent the original road sign ‘home’ to remind us of RAF Tuddenham. Hopefully this will be suitable displayed.

The original road sign to Tuddenham airfield. It has since been returned to Tuddenham for display. (Photo courtesy Herb Zydney)

On leaving Tuddenham, carry on in a south-easterly direction toward Bury St. Edmunds and follow the A14 east. Passing Bury, we arrive at an industrial area on your left. Here we discover an aviation dream world see Trail 16.

Sources and Further Reading.

*1 National Archives AIR 27/731/25

*2 Grehan. J. & Mace. M. “Bomber Harris – Sir Arthur Harris’ Despatch on War Operations“, Pen & Sword, 2014

*3 No. 138 Squadron RAF went on to be the first ‘V-bomber’ squadron of the RAF, flying the Vickers Valiant between 1955 until being disbanded in 1962.

*4 Personal stories of personnel from 90 Squadron at Tuddenham can be found here on the Wartime Memories Project website.

*5 Williams, G. “Flying Through Fire – FIDO The Fogbuster of World War Two“, Alan Sutton Publishing. 1995 (An excellent book detailing the work on FIDO and its installations at each airfield).

National Archives: AIR 27/733/3; AIR 27/733/4

My thanks to Herb Zydney for the You Tube video and photos, they are very much appreciated.