After leaving RAF Wratting Common, we turn south and head back past Haverhill towards Finchingfield. Reputedly one of the most photographed villages in England, it has a ‘chocolate box’ appeal, its quaint houses, old tea shops and village pond, reminiscent of Britain’s long and distant past. Finchingfield and this trail, are also close to the airfield at Wethersfield, and a short detour to the east, is an added bonus and a worthy addition to the trail.

This next airfield, a small satellite airfield, lies one and a half miles to the west of Great Sampford village, and five miles south-east of Saffron Walden. It is actually quite remote, with no public roads close to the site. Footpaths do cross parts of the former airfield, which is all now completely agricultural.

As we head south we stop off at the former airfield RAF Great Sampford.

RAF Great Sampford (Station 359)

RAF Great Sampford was a short-lived airfield, built initially as a satellite for RAF Debden, it would be used primarily by RAF Fighter Command, and later by the US Eighth Air Force. It was also used by 38 Group for paratroop training, and by the Balloon Command.

Being a satellite it was a rudimentary airfield, and accommodation was basic; utilising wooden huts as opposed to the more pleasant brick dwellings found at its parent station RAF Debden. It was very much the poorer of the airfields in the area, although by the war’s end a wooden hut would no doubt have been preferential to a cold, metal Nissen hut!

As a satellite it would be used by a small number of squadrons, No. 65 RAF, No. 133 (Eagle Squadron) RAF and No. 616 Squadron RAF. The famous Eagle Squadrons being manned by American volunteers, 133 Sqn was later renamed 336th Fighter Squadron (FS), 4th Fighter Group (FG), after their absorption into the US Army Air Force.

There were two runways at Great Sampford, one of grass and one of steel matting (Sommerfeld track), a steel mat designed by Austrian Expatriate, Kurt Sommerfeld. The tracking was adapted from a First World War idea, and was a steel mat that when arrived, was rolled up in rolls 3.25 m (10 ft 8 in) wide by 23 m (75 ft 6 in) long. It was so well designed that a full track could be laid, by an unskilled force, in a matter of hours. Each section could be replaced easily if damaged, and the entire track could be lifted and transported by lorry, aeroplane or boat to another location and then reused.

Sommerfeld track (along with a handful of other track types) were common on fighter, training and satellite airfields, especially in the early part of the war. It was also used extensively on forward landing grounds in Kent and later France after the Allied invasion of Normandy.

Tracking had to be robust, it had to be able to withstand heavy landings and be non-conspicuous from the air. Sommerfeld track met both of these, and other stringent criteria very well, although it wasn’t without its problems. Crews often complained of a build up of mud after heavy rain, and concerns over both tyre and undercarriage damage were also extensively voiced. Some records report tail wheels being ripped off after catching in the track lattice.

At Great Sampford the steel matting was 1600 yards long, extended later to 2,000 yards, the grass strip being much shorter at just over 1,000 yards. A concrete perimeter track circumnavigated the airfield, and due to the nature of the area the airfield took on a very odd shape indeed. With many corners and little in the way of straight sections, it may have suited the longer noses of the RAF’s Spitfires well, avoiding the need to weave continuously to see passed the long engine. However, because it was small and uneven, it caused numerous problems for pilots taking off, the hedges and trees proving difficult obstacles to clear without stalling the aircraft in an attempt to get above them.

Hangars and maintenance huts were also sparse, but four blister hangars were provided as the main structures for aircraft repair and maintenance.

Opened on 14th April 1942, the first unit to use the site was No. 65 (East India) Squadron RAF who arrived the same day that it was opened. No. 65 Sqn, being veterans of both Dunkirk and the Battle of Britain, had been moved about to regroup and refit, upgrading its aircraft numerous times before settling with the Spitfire.

The Spitfire VB of 65 Sqn (who were previously based at Debden) was a modified MK.V, the first production version of the Spitfire to have clipped wingtips, a modification that reduced the wingspan down to 32 ft but increased the roll rate and airspeed at much lower altitudes. No. 65 Squadron, would use their Spitfire VBs for low-level fighter sweeps and bomber escort duties, something that suited the clipped wing version well.

Between April and July 1942, 65 Squadron would move between Debden, Martlesham Heath and Hawkinge with short spells in between at Great Sampford. They would then have a longer spell in Kent before leaving for RAF Drem in Southern Scotland. These repeated moves were largely in response to the threat of renewed Luftwaffe attacks on the airfields of southern England, and were part of a much larger plan put into place to protect the front line squadrons.

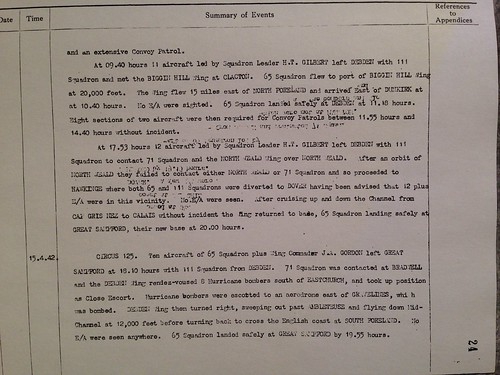

The entry in the Operational Record Book for April 14th shows the first landing of Spitfires at Great Sampford. (AIR 27/594/4)

On April 14th, the move took place, a move that was achieved under some difficulty as the squadron was called upon to participate in two Rodeo (fighter sweeps) operations. After extensive searching between Cap Gris Nez and Calais, no enemy aircraft were sighted, and so the wing returned to their various bases. At 20:00 hrs, the first 65 Sqn aircraft touched down at Great Sampford – the base was now open and operational.

The next mission would be the very next day – there was no let up for the busy flyers! “Circus 125” led by Wing Commander J. Gordon, consisted of ten aircraft from Great Sampford, who after taking off at 18:10, met with the bomber formation and escorted them to an airfield target near Gravelines. The entire mission was uneventful and the aircraft arrived safely back at Great Sampford at 19:55 hrs.

This mission pretty much set the standard for the remainder of the month. Numerous Rodeo and Circus operations saw 65 Sqn repeatedly penetrate French airspace with various sighting of, but little contact with, enemy aircraft. The first real skirmish took place on the 25th, when the Boston formation they were escorting was attacked by fourteen FW-190s. One of the Bostons was hit and subsequently crashed into the sea. Flt. Sgt. Stillwell (Red 3) of 65 Sqn threw his own dingy out to the downed crewman who seemed to make no effort to reach it – he was then assumed to be already dead.

On the April 27th, “Circus 142” took place, the escort of eight Hurricane bombers who were attacking St. Omer aerodrome. Three sections ‘Red’, ‘White’ and ‘Blue’ made up 65 Squadron’s section of the Wing, and consisted of both Rhodesian, Czech and British airmen. The Wing flew across the Channel at 15,000 ft, and when on approach to the target, they were attacked by 50-60 FW-190s. In the ensuing dogfight F/O. D. Davies, in Spitfire #W3461; P/O. Tom Grantham (s/n: 80281) flying Spitfire #BL442, and P/O. Frederick Haslett (s/n: 80143) in Spitfire #AB401, were all reported missing presumed dead. It was thought that both F/O. Davies and P/O. Grantham may have collided as they were together when they went down, P/O. Grantham was just 19 years of age.

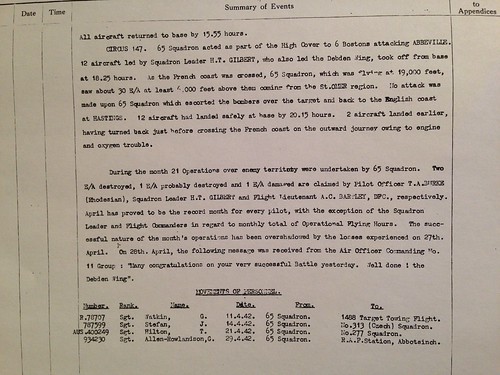

There were no further losses that month although operations continued up until the last day. In all, 21 operations had been flown in which 2 enemy aircraft were destroyed, 1 was a probable and 1 was damaged. April proved to be a record month in terms of operational flying hours for every pilot below the rank of Squadron Leader, the successes of which though, were marred by the sad events of the 27th and the loss of three colleagues.

On the 28th, their last day of this, the first of several stays at Great Sampford, a congratulatory message came though from the Air Officer Commanding No. 11 Group, “Well done the Debden Wing”, which went some way to lighten the atmosphere before the new month set in.*1

The Operational Record Book for 65 Squadron. A message of congratulations from the Air Officer Commanding No. 11 Group. (AIR 27/594/4)

It was three months later on July 29th 1942, that 65 Squadron would depart Great Sampford for the last time, and the next squadron would arrive, the Spitfire VIs of No. 616 Squadron RAF.

No. 616 Sqn were formed prior to the declaration of war in November 1938. An Auxiliary Air Force Unit, it too took part in supporting both the Dunkirk evacuation and the early days of the Battle of Britain. Now, at Great Sampford, it had been given the high altitude Spitfire, the MK. Vl, an attempt by Supermarine to tackle the Luftwaffe’s high altitude bombers, and quite the opposite to the VBs of 65 Sqn – these Spitfires had extended wingtips!

616 Squadron would, like 65 Sqn before them, spend July to September yo-yoing between Great Sampford and the airfields further south, Ipswich and Hawkinge, before departing Great Sampford for the final time on September 23rd 1942 for RAF Tangmere. Whilst here at Great Sampford, they would perform fighter sweeps, bomber escort and air patrols over northern France, engaging with the enemy on numerous occasions.

On the same day as 616 Sqn departed, the last operational unit would arrive at Great Sampford, the U.S. volunteer squadron, 133 Squadron known as one of the ‘Eagle Squadrons’. Being one of three squadrons manned totally by American crews, it had been on the front line serving at RAF Biggin Hill and RAF Martlesham Heath before arriving here at Great Sampford. Whilst some British RAF ground crews helped servicing and maintenance, the aircrew were entirely US, and crews were regularly changed as losses were incurred or crews were transferred out.

Many of these new recruits came in from other units. Ground crews coming into Great Sampford would have to get the train to Saffron Walden where they were met by a small truck who would take them to RAF Debden for a meal and freshen up. Afterwards they were transferred, again by truck, the few miles here to Great Sampford, the transformation was astonishing! In the words of many of those who were stationed here, “there was nothing ‘great’ about Great Sampford!”*2 Also flying Spitfire VBs, they were to quickly replace them with the MK.IX, a Spitfire that was essentially a MK.V with an updated engine. Having a higher ceiling than the FW-190 and being marginally faster, its improved performance took the Luftwaffe by complete surprise.

It would be a short-lived stay at Great Sampford though, as 133 Sqn RAF were disbanded on the 29th September, being renumbered as 336th FS, 4th FG, USAAF, and officially becoming US Air Force personnel. They were no longer volunteers of the Royal Air Force.

Just three days before this final transfer, on September 26th 1942, 133 Sqn would suffer a major disaster, and one that almost wiped out the entire squadron.

A small force of seventy-five B-17s from the 92nd BG, 97th BG and the 301st BG, were to mount raids on Cherbourg and the airfields at Maupertus and Morlaix, when the weather closed in. The 301st BG were recalled as their fighter escort failed to materialise, and the 97th BG were ineffective as cloud had prevented bombing to take place. The RAF’s 133 (Eagle) Sqn were to provide twelve aircraft (plus two spares) to escort the bombers on these raids. After refuelling and a rather vague briefing at RAF Bolt Head in Devon, they set off. Unbeknown to them at the time, the two pilots instructed to stay behind, P/O. Don Gentile and P/O. Erwin Miller, had a guardian angel watching over them that day.

During talks with P/O. Beaty, it was ascertained that the Spitfires had flown out above 10/10th cloud cover and so were unable to see any ground features, thus not being able to gain a true understanding of where they were. Added to that, a 100 mph north-easterly wind blew the aircraft far off course into the bay of Biscay. Finding the bombers after 45 minutes of searching, the flight set for home and reduced their altitude to below the cloud for bearings. Being over land they searched for the airfield, all the time getting low on fuel. Instead of being over Cornwall however, where they thought they were, they were in fact over Brest, a heavily defended port, and in the words of 2nd Lt. Erwin Miller – “all Hell broke loose.” *3

In the subsequent battle, all but one of 133 Sqn aircraft were lost, with four pilots being killed. P/O. William H. Baker Jr (O-885113) in Spitfire #BS446; P/O. Gene Neville (O-885129) in Spitfire #BS140 – Millers replacement; P/O. Leonard Ryerson (O-885137) in Spitfire #BS275 and P/O. Dennis Smith (O-885128) in Spitfire #BS294.

Only one pilot managed to return, P/O. Robert ‘Bob’ Beatty, who crash landing his Spitfire at Kingsbridge in Devon after he too ran out of fuel. During the crash he sustained severe injuries but luckily survived his ordeal. From his debriefing it was thought that several others managed to land either on the island of Ouissant or on the French mainland. Of these, six were known to have been captured and taken prisoners of war, one of whom, F/Lt. Edward Brettell DFC was executed for his part in the Great Escape from Stalag Luft III. A full report of the events of that day are available in an additional page.

There would be no further operational flying take place for the rest of the month for 133 Sqn – all in all it was a disastrous end for them, and to their spell as RAF aircrew.*4

Pilot Officer Gene P. Neville 133 (Eagle) Sqn RAF, stands before his MK. IX Spitfire at Great Sampford. He was Killed during the Morlaix disaster. (@IWM UPL 18912)

Because these marks of Spitfire were in short supply, the remainder of the Squadron were re-equipped with the former MK.VBs, a model they retained into 1943 before replacing them with the bigger and heavier Republic P-47 ‘Thunderbolts’.

As a result of the losses, the dynamics of the group would change. The cohesive nature of the men who had been together for so long, was now broken and the base took on a very different atmosphere.

The effect on those left behind was devastating, morale slumped, and in an attempt to raise it, Donald ‘Don’ Blakeslee ordered the remaining pilots to line up along the eastern perimeter track and take off in formation; something that had been considered virtually impossible due to its short length, uneven surface and rather awkwardly placed trees along its boundary. Blakeslee, who became a legendary fighter pilot with both 133 Sqn and later the 4th Fighter Group (FG), led the group in true American Style, getting all the aircraft off the ground without any mishaps. Heading for Debden, they formed up, and flew directly over the station at below 500 feet, shaking windows and impressing those on the ground with precision flying that took as much out of the pilots as did air to air combat.

That night, the mess hall at Debden, was awash with celebrations as 133 Squadron pilots enjoyed the limelight they had for so long deserved.

On the next day, September 29th, the crews packed their personal belongings and departed Great Sampford for the comforts of Debden, where an official handover took place. General Carl Spaatz and Air Chief Marshal Sir Sholto Douglas, witnessing the official transfer of the three Eagle Squadrons to the United States Air Eighth Air Force, a move that on the whole, pleased the American airmen.

From then on, Great Sampford would remain under control of the USAAF, being used as a satellite for the 4th FG at Debden, but without any permanent residents. The occasional flight of Spitfires or P-47s would land here whilst on detachment or away pending a Luftwaffe attack. In the early stages of 1943, the Americans decided that Great Sampford (renamed Station 359 as per US designations) was no longer suitable for their needs as it wouldn’t accommodate either the P-38s or the P-47s due to its awkward size and shape. By February 1943 they had pulled out, and Great Sampford was returned to RAF ownership. By March 1943 the airfield now surplus to flying requirements, was closed, used only by a large selection of RAF Regiments training in airfield defence, Guard of Honour duties and VIP Security. The station eventually closed in August 1944.

Airmen of the 336th Fighter Squadron, 4th Fighter Group with a clipped wing Spitfire Mk. Vb (MD-A), 1943. at Great Sampford. (@IWM – FRE3230)

However, this closure was not the end for Great Sampford. With paratroop operations progressing in Europe, the airfield was put back into use on 6th December 1944 by 620 Sqn in Operation ‘Vigour‘.

No. 38 Group, in need of practice areas, had acquired the airfield, and were dropping SAS paratroops into the site. This flight preceded another similar activity the following day where Horsa gliders pulled by 620 Sqn Stirlings, took part in Operation ‘Recurrent‘; a cross-country flight from RAF Dunmow in Essex. This flight culminated with the Horsas being released and landing here at Great Sampford. These activities continued throughout the appalling winter of 1944 / 45, and into the following months. In March, in the lead up to Operation ‘Varsity‘ the allied crossing of the Rhine, there was further activity in the skies of this small grass strip. Operation ‘Riff Raff‘ saw yet more paratroops and gliders at Great Sampford, whilst in November 1945, after the war’s end, Operation ‘Share-Out‘ saw the final use of Great Sampford by the paratroops. No. 620 Squadron, who had been based at RAF Dunmow, were now winding down themselves and their use of Great Sampford ceased virtually overnight.

Since then, Great Sampford has become completely agricultural, the perimeter track virtually all that remains of this small but rather interesting site. It lies in a remote area, fed only by farm tracks and small footpaths. The tracks, now a fraction of their original size, still weave their way around the airfield as they did for that short, but busy time, in the mid 1940s.

Regretfully the airfield and its unique history has all but passed into the history books, and rather sadly, no memorial marks the airfield, even though many airmen were lost during the many sorties in those dark days of the war-torn years of the 1940s.

We depart Great Sampford heading off once more, the airfields of Essex and East Anglia beckoning. As we move off, we spare a thought for those for whom this was the last view they had of ‘home’, and of those who never came back to this quiet and remote part of the world.

Sources and further reading

*1 National Archives: AIR 27/594/4 .

*2 Goodson. J,. “Tumult in the clouds” Penguin UK, (2009)

*3 Price. A., “Spitfire – A Complete Fighting History“, Promotional Reprint Company, (1974).

*4 National Archives: AIR 27/945/26

National Archives: AIR 27/945/25

The “Slightly-out-of-Focus” website has details of a photo essay documenting the planning and execution of an airborne exercise prior to Operation Varsity. It’s a detailed document which includes gliders of 38 Group RAF landing at Great Sampford.

Yet another thoroughly researched post! It’s a shame that there’s no memorial of any sort, as it has an interesting and tragic history. Could that change in the future?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for the kind words! As for the memorial – who knows! The Airfields of Britain Conservation Trust do go around placing memorials at forgotten airfields, but it’s slow and money has to be raised. Personally, I think it unlikely unless a particularly interested party comes along, which is a unlikely and a shame.

LikeLike

As usual, fantastic stuff!

Thank you for posting 👏

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you John, I’m glad you enjoyed it.

LikeLike

Another excellent account, as always! I’ve been reading about circuses and rhubarbs and so on in “Hornchurch Offensive” and the statistics there are frightening. You can only presume that they called them ‘circuses’ because the idea was thought up by clowns. More or less, all the battle hardened survivors of the Battle of Britain, for example, had been killed off by 1942. It’s a good book, if you ever come across it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you John, it’s always good to know I’m on the right track! Perhaps you are right there were a lot of clowns in charge making some rather dodgy decisions! The book sounds interesting I shall keep a look out for it, thanks for the tip!

LikeLike

Reblogged this on PenneyVanderbilt and commented:

Great reading even for stupid Americans

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ha ha I’m sure you’re not. Thank you for the reblog.

LikeLike

Each of your posts gives us more and more of outlook into that world war. Excellent research!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you. There’s always so much more that could be added!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know what you mean!!

LikeLiked by 1 person